When Movie Moguls Wage War to Protect Copyright, the First Amendment Ends Up on the Cutting Room Floor

by Jeff Howe (May 3-9, 2000)

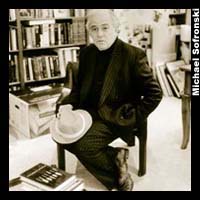

The writer's lawyer: Attorney Martin Garbus represents the cyberjournalist who posted a DVD-hacking program.

In the world of Martin Garbus, we are all teachers and he is the student. This at least partly explains why an otherwise innocent DVD player lies in pieces on the coffee table in his Madison Avenue law office. The teacher today is Chris DiBona, prominent evangelist of the open-source creed - the belief that computer code, like speech, wants to be free.

DiBona is teaching Garbus, who only recently learned how to work his own e-mail, why a miniscule bit of silicon in this player - and an equally miniscule program built to bypass it - have sparked a federal case that will determine whether we pass through the digital age with the First Amendment intact.

As DiBona speaks, pointing at various organs in the innards of the DVD player, Garbus leans forward and listens intently. Very intently. You can almost hear the sound of files shifting and expanding inside Garbus's cerebrum. The force of this man's concentration could bend spoons, or laws. "I chose this life so I could forever remain a student," Garbus says, in a not-infrequent display of mock humility.

This life, as it happens, has also allowed Garbus to remain a high-profile rebel. Perhaps the closest thing in New York to a modern-day Daniel Webster, Garbus has made a living by fighting the dark side in all its forms. A laundry list of Garbus's clients reveals a Zelig-esque talent for being on the right side of the right fight at the right time. Garbus fought for Lenny Bruce in '64, for Timothy Leary in '66, and against Alabama governor George Wallace in '68. A few years later he hid the Pentagon Papers in his attic for reporter Daniel Ellsberg. He has argued before the Supreme Court on 20 occasions, winning each time. Garbus has fought to protect the copyright of work by Samuel Beckett, Robert Redford, Al Pacino, and John Cheever.

The hacker's writer: Web scribe Eric Corley launched a First Amendment fight when he posted a program that breaks the code of DVDs.

So why has Garbus, with his eye for the limelight and his zeal for the sanctity of intellectual property, taken on the cause of a Long Island cyberjournalist accused by the Motion Picture Association of America of being a copyright thief?

"He gets it," says his client, Eric Corley, publisher of the quarterly journal 2600, commonly referred to as the "hacker bible," and enemy number one of big Hollywood.

Last fall Corley, who goes by the nom de Net of Emmanuel Goldstein, posted to 2600 a program that allows technology-savvy folk to decipher the code of DVDs and then view the films on unlicensed players. The open-source set calls this a First Amendment right. Hollywood calls it piracy and fears a brave new world where people get their movies on the Web for free. In January, the motion picture association slapped Corley and two other defendants with a federal suit alleging copyright violation.

When Corley says Garbus "gets it," he's offering no light praise, since factual error, bald deception, and simple misunderstanding have obscured what initially looked like an open-and-shut case for the motion picture industry. The movie moguls are banking on the Digital Millennium Copyright Act of 1998, which expressly forbids providing anything "primarily designed or produced for the purpose of circumventing a technological measure that effectively controls access to a [copyrighted] work." In plain English, that means you can't hand out a tool that breaks through copyright protection.

The tool now in question is DeCSS, which appears to smash those barriers, bypassing the Content Scrambling System that guards DVDs and allowing users to do with the contents what they will.

Armed with that premise, Hollywood took round one by a rout in January, as a federal district judge granted an injunction that blocked Corley and the other defendants (who have since been dropped from the suit) from posting DeCSS. But Corley battled back, posting a collection of links to sites around the world willing to offer the program. That prompted the motion picture association last month to ask that the injunction be extended to ban such links.

By any account except Hollywood's, granting the request would be an egregious gagging of free expression. A newspaper like this one, for instance, would be forbidden from telling its readers how to find the source code to DeCSS on cryptome.org. This so-called prior restraint is a special bugbear of the fourth estate. No surprise, then, that The New York Times has expressed its concern and may file a brief on behalf of Garbus and his client.

For his part, Garbus will submit that DeCSS is an exercise in cryptography, an innovation in interoperability, and protected speech to boot. Under that argument, the program should be covered by the "fair use" principle of the First Amendment - putting the Digital Millennium Copyright Act and freedom of expression at irreconcilable odds.

The case for the defense does not look good. The entertainment industry is garnering court victories in the fight between the right of commerce to protect intellectual property and the right of Netizens like Corley to speak their minds. Last week, a federal judge in New York ruled for the Recording Industry Association of America in its copyright infringement suit against MP3.com, which allows users to post and download CDs for online listening.

Garbus knows lower courts are not often inclined to contradict Congress, so he's already plotting strategies for appeal all the way to the Supreme Court. The matter is being closely followed by Internet wonks, pundits, and practitioners, not to mention those civil libertarians who "get it."

"If the judge finds for the plaintiff, and the decision isn't knocked down on appeal," says Yochai Benkler, a professor of information law at New York University, "it will create an environment that's closed like nothing we've ever seen before."

Welcome to the latest front in the war for the First Amendment.

Eric Corley looks like a hacker. All stringy black hair, pale skin, and hunched shoulders, Corley has the unmistakable pallor of someone who spends most of his time alone in front of a computer screen. Hollywood could not have picked a better physical specimen for their relentless campaign to portray the open-source community - programmers and users of operating systems and software whose source code is freely available - as "thieves and pirates."

But Corley fails that test in one important regard: He does not hack. He "couldn't hack his way into a paper bag," says one ex-hacker who, naturally, chooses to remain anonymous.

No electronic trespasser, Corley is a journalist - and not one lacking in considerable credentials. His journal 2600, founded in 1984, boasts a circulation of 60,000. Between 10,000 and 15,000 visitors drop by the site. Corley hosts a weekly radio broadcast and has appeared on numerous talk shows, including Charlie Rose, Nightline, and 60 Minutes. He has testified before Congress and written editorials for the Times and the Daily News. He gave the commencement address when he graduated from SUNY Stony Brook. He says the movie moguls didn't know how much fight they'd get when they homed in on him. "It was foolish of them to pick [2600]," Corley says. "We've always stood up against this kind of thing. We don't know how to back down."

The fact that Corley is a scribe for the hacker world may make him a likely suspect for the motion picture association, but not necessarily a wise one. Corley counts among his admirers - and readers - countless programmers and academics. Oddly, the same logic that made him a target for the movie industry also made him a client that Garbus couldn't pass up.

In the DVD trial, the First Amendment lawyer found a story with clearly drawn opponents worthy of a pulp-fiction plot: a powerful, wealthy industry versus a corps of overworked, denigrated protectors of civil liberties. This is white hats against black hats, heroes facing up to villains, good law butting heads with bad.

With self-righteous zeal, the motion picture association has harassed open sourcers and free-speech advocates who have posted, or merely linked to, the program once offered by Corley. Soon after Hollywood realized movie discs had been hacked, they fired a salvo of cease-and-desist letters to anyone offering DeCSS. On December 28, the trade organization in charge of licensing movie rights for DVD players filed suit in California, naming 21 individuals and "Does 1-500, inclusive." That's Does as in John, a deft bit of legal language that allows the plaintiff to attack retroactively anyone it chooses. In mid January, Norwegian authorities raided the Oslo home of 16-year-old Jon Johansen, who is accused of first providing DeCSS on the Web.

From the beginning, the movie association has made little effort to disguise its enmity toward the hacker community, calling them "nerds" and "anarchists." The group has sent cease-and-desist letters to people in Germany and Australia, places far outside the jurisdiction of injunctions issued in the United States. A 2600 correspondent in Connecticut has been targeted with another federal suit, and a University of Wisconsin student was fired from his job at a computer lab after a letter from Hollywood landed on his boss's desk.

For Garbus, the plight of the open-source community is clear. "There is little question in my mind this persecution of hackers is, in many respect, analogous to the Communist red-baiting of yore," he says. "They are being unfairly maligned, and stigmatized, without due cause."

According to John Gilmore, the co-founder of the Electronic Frontier Foundation, a civil-liberties group that has picked up the defense tab in all the DVD suits, the program Corley posted was originally one part of an open-source project to develop a movie disc player for the Linux operating system favored by hardcore programmers. Linux supporters saw Hollywood's tactics as a call to arms. They posted thousands of copies of DeCSS throughout the Web as a show of support for Corley.

And if the online proliferation weren't enough, the lawyers representing Hollywood accidentally entered the entire DeCSS source code into the public record.

All this for a program that Corley and much of the computing community insist doesn't even do what the film executives say it does: encourage the copying of DVDs. Corley argues DeCSS exists solely to allow people to view movies they own on unlicensed players, like ones that run on Linux - an operating system Hollywood refused to license. "You have to wonder, why are they so upset at people knowing how to use their technology?" Corley says. "They don't care about copying. Copying is easy. People have been copying for ages. There are whole warehouses in Asia copying DVDs and nothing else."

Yet when the film industry first filed suit in California last November, president Jack Valenti raised the specter of marauding hackers and thieves out to defraud Hollywood. Valenti told Daily Variety: "[W]e don't have broadband access today, so we don't have many [pirated] movies on the Internet today . . . By the middle or end of next year, we will have an avalanche."

But a month before Valenti's apocalypse was scheduled to appear, a lawyer for the industry group admits he, the former deputy director of the antipiracy division, has yet to uncover a single instance of piracy using DeCSS. "Do I know of any incidents of piracy, personally? No," says Greg Goeckner. "But I would have to check with my team in the field."

The movie association may have a hard time uncovering any pirates sailing under the DeCSS flag. Gilmore, of the Electronic Frontier Foundation, explains that DVD movies are far too big for easy duplication. "The only place you could store your movie would be on your hard drive," he says, "and even then you could only hold four such movies at most." Gilmore also points out that it could take hundreds of hours to download a DVD over a 56k modem, so merely transferring these files would mean disabling your computer for weeks, all for the purpose of gaining a bootleg copy of The Matrix. The film association hasn't found any instances of DeCSS piracy for one simple reason: There's no cause to do it.

If DeCSS isn't likely to be used for pirating movies, why does the program pose a threat so dire that Hollywood turned to the courts for relief?

This will be one of Garbus's first questions, if he ever sees the courtroom on Corley's behalf. On April 25, attorneys for the movie association filed a motion to disqualify Garbus from the case. Garbus's firm, it turns out, represents Scholastic in an unrelated case. Time Warner, a member of the association, owns Scholastic, and you're not supposed to defend and attack the same client at the same time. This technicality may be enough to kick Garbus out of the suit. "He probably has a 50-50 chance," speculated one legal observer close to the action.

If Hollywood wins, Garbus is gone, barred from appearing for Corley as counsel. The Electronic Frontier Foundation and Corley go back to soliciting solicitors, their appeal enhanced through association with Garbus.

If the motion fails, the movie execs will have a formidable foe on their hands. War is hell and so is law, and Garbus sees little difference between the two.

But a firebrand trial lawyer isn't all Corley gets. Garbus is an icon of "East Coast Code," a term coined by Lawrence Lessig to describe the legal code. Garbus must now convince the court to consider the rights of "West Coast Code," or source code.

He will argue that DeCSS falls under the First Amendment's fair-use exception to the Copyright Act. The doctrine of fair use permits, for example, a reporter to quote paragraphs from a book or print sections of a pamphlet.

In the case of DVDs, the only way a consumer can copy specific portions is to use DeCSS. Barring people from doing that is a more insidious encroachment on individual liberty than it first appears. "Say you want to criticize the liberal leanings of Hollywood, or criticize the sexist movie of this or that," says Benkler, the NYU law professor. "You need to be able to quote little pieces of the movie. You can do that under the copyright law, because that's fair use, but using DVDs lawfully as the [film association] reads the law, you can't do that. This really extinguishes user privilege to an unprecedented degree."

This same privilege was tried - and survived - in an oft-cited suit in 1984 involving Betamax, which manufactured early video recorders. The question then was the same one asked now: whether the entertainment industry's right to safeguard its products carries more weight than the right of individuals to access copyrighted works for their own expressive, and protected, ends.

The First Amendment also protects a process called reverse-engineering, which was used to create DeCSS. Reverse engineers take things apart in order to learn how to put them back together in a better form.

In other words, to build a better mousetrap. The right to take things apart - whether breakfast cereals or pharmaceutical compounds - is a time-honored tenet in American law, held to encourage innovation.

So far, judges have been friendly to reverse engineers. This year, the Ninth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that Connectix's Virtual Game Station, which allows Mac users to play Sony PlayStation games on their computers, had not violated copyright law because it was reverse-engineered from PlayStation.

In the case of DeCSS, the upshot is that the program is already out there. The DVD encryption was a flimsy system that everyone in the open-source world knew would be hacked, sooner rather than later. East Coast Code may enjoin open-source programmers and "pirates" from posting and trading DeCSS, but with an estimated 300,000 copies already in existence, only West Coast Code, i.e., a better encryption scheme, is going to maintain Big Hollywood's grip on user privilege. In the Wild, Wild Web, you're responsible for your own fences. East Coast Code don't mean shit.

(https://www.villagevoice.com/news/0018,howe,14548,1.html)