More Cellular Fun

by Judas Gerad

In the Spring 1993 issue of 2600, Bootleg did an admirable job with his article "Cellular Magic." There are a few things that would be helpful if clarified, so let's do it. I'll assume you read Bootleg's article and have some understanding of the cellular network.

Unless a hacker is quite adept at both hardware and software coding, the item of interest residing in a phone's firmware is the Electronic Serial Number (ESN). On the phones I've worked on, the ESN is stored in a separate, discrete PROM. While some of the newer phones may indeed incorporate the ESN into a VLSI chip with the operating software and Number Assignment Module (NAM), the vast majority of the units floating around don't. The ESN is not contained in the same chip as this other data.

I've run into many people who thought the PROM (or E(E)PROM) containing the phone's parameters such as MIN, SIDH, lock code, etc. was the same chip holding the ESN. It's not, and this becomes obvious when you realize that until a few years ago, these parameters had to be bummed into a new chip by the dealer when you bought your phone and were assigned a number, or changed service.

Placing the ESN in the PROM serving as the Number Assignment Module (NAM) would be a de facto deviation from the EIA standard for cellular phones. This specification states: "The circuitry that provides the serial number must be isolated from fraudulent contact and tampering. Attempts to change the serial number circuitry should render the mobile station inoperative." It's obvious the manufacturers didn't do a very good job in this respect, or cellular fraud wouldn't have reached the $300 million per year mark so quickly. It's no wonder cellular fraud is becoming the medium of choice for hackers who are hip enough to push the envelope. It should be interesting to see what "boxing" techniques develop in the cellular arena.

Where the Hell is the ESN?

Getting back to the lonely little PROM with the ESN, once you know it's not in the EPROM serving as the NAM, or tucked away with the operating code for the phone, it becomes easier to locate, remove, and read (and change, if that was your desire).

The package burned with the ESN is often a 16-pin DIP style Surface Mounted Device (SMD). Don't confuse this with the large 256-bit (2x8) PROM or E(E)PROM used as the NAM. The ESN may be stored in a 32x8-bit chip, but it sure won't be sitting in a socket. The service manual for the G.E. Mini portable phone shows the ESN located in a Ricoh RF5H01 64-bit PROM. Interestingly, this 8-pin IC is soldered all by itself on the foil (trace) side of the logic circuit board instead of the component side with everything else. It's either shy or a loner, and decided to hide from the larger chips and hackers alike.

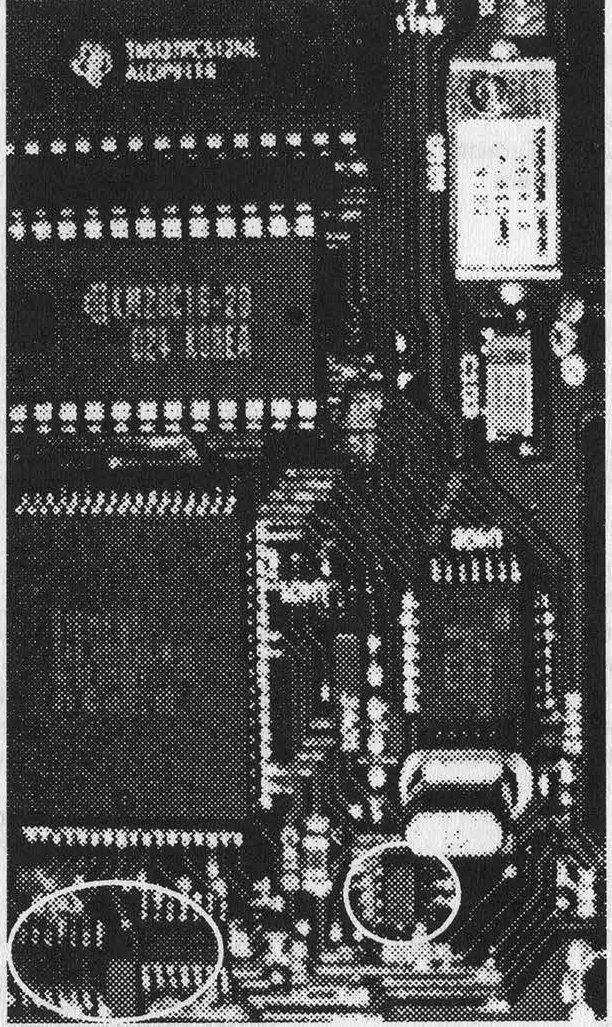

The photograph with this article is provided to give you a feel for what we're discussing. Not being one of the geniuses who can rewrite phone software, I don't know for a fact which chip contains the ESN on this model as I haven't researched it. None of the large chips to the left of the board are the ESN PROM. One of the small SMDs below the microprocessor or the tiny 8-pin IC below and slightly to the left of the crystal are likely subjects for closer scrutiny. If there is enough interest, perhaps we'll eliminate the challenge by publishing a close-up photo of the correct chip... but that takes the fun out of it!

In closing it is important to note that there is no single answer as to where the ESN is stashed. This varies from manufacturer to manufacturer, and even phone to phone. As the hardware evolves and phones get smaller and smaller, the use of custom "Very-Large Scale Integration" (VLSI) circuits increases. In those instances, the ESN could easily be buried in the same chip as the NAM or operating software.

ESN Downloading

An interesting note in this area is the recent discovery that Motorola and perhaps others have cut costs by designing late-model phones with circuitry that allows the ESN to be downloaded into the phone after manufacture rather than by mounting a pre-burned chip during assembly. There is at least one device that has recently become available that will interface your IBM PC to the phone in order to change the ESN at will. If that sounds interesting, I hope your subscription to 2600 is current. I'd feel badly if you missed our review of the product.

Caller ID

The topic of Caller ID isn't particularly relevant to cellular hacking, especially since carriers almost never pass Caller ID information from the network to the local telco. This degree of anonymity is one of the nice attributes of cellular communications.

There have been numerous letters requesting information on Caller ID, especially looking for techniques to defeat the service. Unfortunately, the outlook is grim in this area, as you'll see.

For a telco to offer the Caller ID service, the local ESS switches must be of a sufficiently recent revision and be Signaling System 7 (SS7) capable. Caller ID data, whether generated by the switch itself in the case of local calls, or sent through the SS7 network with the other call setup information, is eventually dumped down your phone line to be captured by your display device, modem, or CID-to-RS-232 converter and displayed on your PC.

This signal is applied to your line after the first full ringing cycle during the "silent period" between the rings by the Voice-Band Digital Interface (VDI) contained in your local switch. The data is transmitted as a 1200 bps asynchronous, ASCII-encoded simplex FSK data stream. The standard used is just like the Bell 202 modem specification, with the mark frequency being 1200 Hz and the space (logical zero) represented by 2200 Hz.

The problem with developing Caller ID countermeasures lies within the nature of ESS. These switches establish no actual connection between the calling and called lines until after the phone has been answered (and the Caller ID data has been transmitted). This is the same thing that rendered the "Black Box" totally useless.

If you are not connected to the number you are calling until after the Caller ID data has been dumped, I don't know of a way to introduce any modified data. You can't even do much after the person has answered because the Caller ID display units depend on a "ring detector" to sense when the phone is ringing to activate and apply AC termination to the line and attempt to sync up with the data stream. Once the voice connection is established and the called party is off-hook, the display device will ignore anything you dump down the line.

A Solution on the Horizon?

There is a possible solution to this dilemma, but it requires the ability to access your switch's programming. Since certain telcos (like Nevada's Centel) cooperate with law enforcement by programming the switch to send a fake number via Caller ID to assist in sting operations. It wouldn't surprise me if hackers renewed their efforts to obtain dial-up access to their local ESS switch...