MARCH OF THE TITANS - A HISTORY OF THE WHITE RACE

CHAPTER 14 : ROME AND THE CELTS

Europe had been settled by a number of waves of Nordic Indo-Europeans, sweeping out of their homeland between the Black and Caspian seas, from about 4000 BC onwards. There were any number of tribes: some long since forgotten or amalgamated with the bigger tribes - others significant enough to have created regions or states later to be named after them: these included the Britanni, Slavs, Balts, Germans and others.

Despite their differing tribal names, they all shared a common Nordic sub-racial root. Depending on the nature of the original European populations they encountered in the various parts of Europe, they either retained their Nordic characteristics or they were diluted amongst the Alpine or Mediterranean populations.

In this way the population of northern and large parts of Western Europe became more Nordic, while parts of France, Spain, Italy and central Europe became less so.

THE BALTS - RETAINED TRADITIONS LONGEST

The Balts were the northernmost wave of the Indo-European tribes, settling in north eastern Europe around the Baltic sea, to which they gave their name. The Balts were unique in the sense that they were the only original Indo-European tribe not to have had direct military contact with the Romans.

This was due to the fact that once settled in the north eastern reaches of Europe, the Balts never tried to expand further: the only Indo-European peoples not to engage in any further land grabbing exercises.

probably because of this isolationist policy, they kept to the ancient Indo-European traditions the longest, with even their languages to this day retaining similarities with the Indo-European mother tongue.

The Balts also kept closely to their old Indo-European religions, with worship of the old deities still being carried out as late as 1900 AD.

THE CELTS IN FRANCE AND THE ROMANS

By 600 BC, the Celts had firmly established themselves in France, although those in the southern parts of France were darker (because of the greater Mediterranean population originally living there) than those in the northern parts.

These Celtic tribes lived in relative stability in small villages and towns, with a strongly developed sense of social status - the aristocracy were almost always warriors, while the middle and lower classes were the tradesmen and laborers.

As the Celts were not literate, virtually all the descriptions of their lifestyles come from Roman writers, including that of Julius Caesar himself, who was head of the Roman army that occupied Gaul in 54 BC. Caesar wrote an account of his campaign in Gaul, and noted the differences between the Gauls in the north and the south.

Dying Gaul, Roman sculpture, circa 230 BC. An excellent portrayal of the racial characteristics of the Gauls with whom Rome was to do battle.

GAULS FOUND MILAN AND ATTACK ROMANS

The enmity between Rome and the Celts (or Gauls, to give them the name that they had by the time of the Roman occupation of France) went back to 400 BC, when Celtic armies invaded northern Italy and founded the city of Milan.

In 387 BC, they even occupied the city of Rome, leaving only after the Romans paid them a ransom of gold.

Other Celtic tribes struck further south, with one group, the Galatae, reaching Turkey, becoming the Galatians mentioned in the Christian Bible. Yet another group settled in what became Yugoslavia, founding the city of Belgrade.

A Roman sculpture of a (French) Gaul chieftain. An excellent depiction of a Gaulish nobleman from the time of the Roman invasion of modern day France.

ROMAN REVENGE

The Romans bided their time and built up their strength. After a series of minor clashes, Roman armies under general Caesar rolled into Gaul in 54 BC and smashed the Celts, enslaving virtually the entire population, over three million by Roman counts.

The cruelty with which the Romans suppressed the Gauls was to trigger one last great uprising. Began by a tribe in central France, the rebellion spread out and carried on for two years, eventually being led by the king of the Arverni tribe, one Vercingetorix.

Spurred on by fresh Roman outrages - when Caesar occupied the Gaulish town of Avaricum, for example, he ordered all 40,000 inhabitants put to death - Vercingetorix and his Gaulish allies very nearly defeated the Roman armies.

For a while the Roman expedition nearly foundered, but eventually superior Roman organization won the day. Vercingetorix and 80,000 of his men were finally cornered in the fortified town of Alesia on the Seine river. Caesar's army settled down to a siege, preparing their defenses well enough to ward off attacks by Vercingetorix's allies outside.

Finally, in an attempt to save his people from extermination, Vercingetorix personally surrendered to Caesar in 52 BC.

Caesar had the Celtic King sent to Rome in chains, where he was kept prisoner for six years, before being publicly strangled and beheaded.

The Gaulish rebellion at an end: Vercingetorix surrenders to Caesar. After conquering modern day France and moving on to Britain, Caesar had to rush back to Gaul to face a full scale rebellion led by the great chief Vercingetorix in 52 BC. After cornering and besieging the Gauls at Alesia on the Seine River, the Gaulish chief personally surrendered to Caesar in an attempt to save his own people. Caesar had the Gaul sent to Rome in chains where he was kept prisoner for six years before being executed.

THE CELTS IN BRITAIN AND THE ROMANS

The island of Britain had in the interim also been settled by waves of Celts, producing the same sub-grouping mix as had happened elsewhere in Europe. Generally though, the Celtic Britons were not as Nordic as their Celtic cousins across the channel in France, this being due to the fewer number of Nordic Celts actually crossing the channel to mix with the Alpine/Mediterranean Neolithic population in Britain.

The Celtic Britons further built up and advanced on many Neolithic structures already existing in Britain.

Many of the ancient hill forts in southern and western England were for example rebuilt and further strengthened, for, like Celts everywhere, they were just as apt to fight with each other as with anyone else.

Yet more Celts moved across to Ireland, taking the ancient Indo-European language with them: the very name Eire is, like Iran and Iraq, derived from the word Aryan. Eire was never settled by the Romans (although they did have one fort outside Dublin, but this appears to have been an emissary party only) and thus remained known as Celtic strongholds.

Pre-Roman Celtic Britain is best described as iron age, although the country was essentially Neolithic with agriculture as its main activity. Contact with the outside more developed world existed, with evidence of trade even with Rome, being fairly abundant.

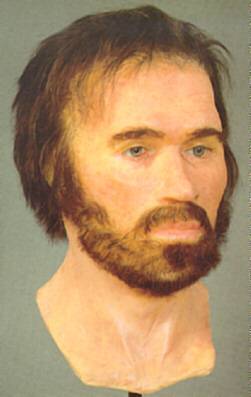

Reconstruction of the head of Lindow man, the Iron Age body found in a Cheshire, England, peat bog in 1984. Dating from around 100 AD, this would have been the typical type of Celt that the Romans would have encountered, fought against, and finally mixed with, in Britain. On display in the British Museum, London.

FIRST ROMAN INVASION - 55 BC

In 55 BC, Caesar, fresh from subduing the Gauls in France, undertook the first Roman crossing of the channel to Britain. He managed to land a sizable army, but his emissary to the Celtic tribes of south eastern Britain, a Romanized Gaul named Commius, was captured by one of the Celtic tribes.

The Romans were also surprised to find that the Britons had war chariots - another skill imported from their Indo-European homeland - and the Roman cavalry, which was the only weapon which Caesar might have been able to deploy against the chariots, had not managed to cross the channel due to bad weather.

For a while it seemed as if Caesar's two legions would be driven out of Britain - but his Gallic emissary (who had been released as part of a diplomatic cat and mouse game) managed to gather together some local horses to whittle down the advantage of the British chariots.

A stalemate was achieved after a particularly inconclusive battle - but it was the respite that Caesar needed, and shortly thereafter the bulk of the Roman legions withdrew to Gaul, with Caesar himself being feted in Rome for the expedition, although it was minor in comparison to the far more significant conquest of Gaul.

SECOND ROMAN INVASION - 54 BC

The following year, 54 BC, Caesar however launched yet another invasion of Britain. This time he landed a force several times larger than his first expedition, including some 2,000 cavalry. He hoped to land his forces and march quickly into the heart of the Celtic territory and inflict a defeat upon the scattered tribes before they could unite into one army.

However, he chose his landing beaches poorly. To compound his problems, a storm forced him to spend ten days dragging all his ships onto the dry land to prevent them from being sunk, giving the Britons enough time to sound the alarm and to draw up their army under a leading tribal chief named Cassivellaunus.

Nonetheless, the overwhelming force which Caesar had drawn into Britain, defeated even the united Celts. The defeat caused the Celtic alliance to wither, and some significant tribes even went over to the Roman side, the most important being the Trinovantes of Essex, who had reason to disapprove of Cassivellaunus because he had, in an earlier skirmish, slain their chief.

Cassivellaunus went on the offensive, attacking a major Roman camp in Kent, but was defeated. Caesar's victories were not however complete. The early loss of time meant that winter was now approaching and he had still not achieved his outright conquest. Even worse, rebellion was brewing in Gaul across the Channel. He and Cassivellaunus then agreed to a peace whereby the Celts would pay an annual tribute to Rome and would safeguard Roman interests in Britain. Thus concluded, Caesar hurriedly left Britain to return to Rome and then back to Gaul, where he had to face Vercingetorix's uprising.

Romans landing on the British shore. In 55 BC, Julius Caesar and a Roman army landed in Britain, and was surprised to find stiff resistance from the Celts resident on that island. Great was his surprise when he also found that the Celts had chariots, and it was only after an inconclusive battle that a stalemate was reached which allowed Caesar to leave without conceding defeat. Caesar launched another invasion of Britain in the following year, and this time managed to subdue a larger number of Celts. Most of the country remained independent however for nearly another 90 years until 43AD when a renewed Roman offensive subdued virtually all of present day England.

Any thoughts Caesar may have had of a third invasion of Britain were shelved by the subsequent events which occupied his life - the suppression of the Gallic rebellion - the march on Rome in 50 BC - his assumption of power and his assassination a few short years later.

CAESAR'S CONQUEST OF SPAIN

Caesar did however manage to conquer Spain in a short six week campaign in 49 BC - bringing virtually all the Celts in that country under Roman rule (previously only a southern part of Spain had been in Roman hands, seized from the Carthaginians during the Punic Wars). The process of Romanization of Spain also began in earnest after this date.

THIRD ROMAN INVASION OF BRITAIN - 43 AD

Caesar's successor, Octavian Augustus, planned a number of invasions of Britain, but all were postponed due to pressures elsewhere in the Empire requiring more immediate action. Thus Britain lived for another 100 years in a state between full Roman occupation and full independence.

It was only in 43 AD, that the emperor, Claudius, finally ordered a full conquest of Britain. Claudius assembled an army of 40,000 men under the command of Aulus Plautius and invaded the island in that year. The overwhelmingly powerful Roman armies quickly swept inland, defeating determined Celtic resistance around present day London. Claudius himself decided to be present at the final victory, and landed in Britain with additional forces and elephants - which must have seemed like dragons to the British Celts - and occupied the main Celtic city of Colchester.

There the Celtic tribes formally surrendered, and Claudius was able to leave after a stay of only 16 days, finally having added the province of Britain to the empire.

The Roman forces spread out from Colchester, employing powerful weapons such as bolt catapults against tribesmen armed with only bows, arrow and slings. Nonetheless, the Celts defended to the death places such as the ancient hill fort of Maiden Castle in Dorset.

CELTIC REBELLION UNDER BOADICEA

In 47 AD, there was an increase in Celtic resistance which simmered on until 61 AD, when it finally erupted into open revolt under queen Boadicea of the Iceni tribe in Norfolk. The death of the Iceni king brought a Roman unit into their territory, which, after engaging in a bout of looting, then publicly whipped the king's widow, Boadicea, and raped her daughters.

This public shaming proved too much. The Iceni and many other Celtic tribes broke out into open revolt, and took several Roman strongholds, including Colchester and London, both of which were sacked and burnt down with 70,000 Roman and Romanized Celtic fatalities. Shaken, the Romans drew together their forces and met Boadicea's army in the middle of Britain, where, through superior organizational ability and better training, the Romans were able to inflict a massive defeat upon their numerically superior enemy, slaughtering, the Roman version says, some 80,000 Britons on the field for the loss of only 400 Roman soldiers.

The Boadicean revolt was the last major native rebellion the Romans experienced in Britain for the next two hundred years.

Queen Boadicea of the Iceni in her chariot leading the Celtic rebellion against Roman rule in 61 AD. At first she won some great victories, overrunning the Roman towns of Colchester and London. Noted as having long blond hair by the Romans, the Celtic queen was finally defeated by superior Roman organization at the battle of Loughton. Retreating to the great forest today known as Epping to the north east of London, she took poison in order to avoid capture.

From then on the military conquests of other parts of the island, reaching north into lower Scotland continued without major interruption until by 80 AD they had pushed the most rebellious Celts up into the Scottish Highlands. (The Scots themselves were originally an Irish Celtic tribe who crossed the Irish sea at a later date).

One of these rebellious tribes, the Caledonians, nearly defeated the Roman legions pushing north at the battle of Mons Grapius in 83 AD, but once again the Romans prevailed, and the Caledonians vanished into the Highlands. However, the ferocity of the far northern Celtic defense meant that the Romans never pushed home the advance (although they did sail a fleet round the top of Scotland) and slowly withdrew southwards.

By 122 AD, the Roman emperor, Hadrian, had not only visited the province of Britain but had also ordered the building of a fortified wall across the north of England to keep the tribes to the north out. Many parts of this wall, named after Hadrian, can still be seen to this day.

Hadrian's Wall, northern England. Built by the Romans to ward off the incessant attacks by the Celts (called Picts) whom they had been unable to subdue in the far north of that country.

By 212 AD, the Romans were firmly entrenched in England (as opposed to Britain) and the process of Romanization was well under way. This was speeded up by the edict of Caracalla in 212 AD granting Roman citizenship to all free inhabitants of the Empire, and the resultant legalization of the already de facto situation of soldiers taking wives from the local population.

This policy, implemented throughout the Empire, did not have the same effects on the Romans in Britain or France as what it had on the Romans in the Middle or Near East - the mixing of Roman, Celtic and original European sub groupings did not disturb the racial homogeneity of either the conquerors or the conquered peoples - they remained overwhelmingly White, while in other territories the local Nonwhite populations soon swallowed up the White element.

In 287 AD, a revolt once again broke out in Britain, even though by this stage many Romans had become Britons and vice versa. In fact the rebellion was led by Romanized Britons and Romans who disliked the emperor of the time, Maximian (appointed as co-emperor by Diocletian). A specially dispatched Roman army had to subdue the Britons and the Roman rebels by force in 296 AD.

According to the Roman records, the rebels employed a large number of German mercenaries - ironically, many of the newly arrived Roman legionnaires were also German mercenaries. This rebellion was the last major armed action undertaken by the Romans in Britain.

ROMAN CONTROL LOST DE FACTO CIRCA 400 AD

While not mirroring the racial situation in Rome (which had by the 2nd Century AD become quite mixed with a substantial Nonwhite influx into the Roman bloodline), Britain did however experience political instability caused by the infighting and squabbling amongst the slowly darkening Romans in Rome itself. Control over the far flung empire became more remote, till finally around 400 AD Rome had de facto lost control over their northernmost province. By this time Britain was experiencing a new wave of Nordic invaders - the Saxons and other Teutonic peoples sweeping in from Northern and Central Europe.

or back to

or

All material (c) copyright Ostara Publications, 1999.

Re-use for commercial purposes strictly forbidden.