MARCH OF THE TITANS - A HISTORY OF THE WHITE RACE

CHAPTER 24 : THE NORDIC RESERVOIR - SCANDINAVIA

Scandinavia became the very first settling areas for the Indo-European tribes in Europe - in fact they were settled so long in this region that the scientific name for their racial type, Nordic, came to be associated with the region itself, hence the oft used term "Nordic countries."

The history of the Scandinavian countries; Denmark, Norway, Sweden and Finland; are intertwined. For long periods these countries ruled each other, while in Finland's case, war with Russia dominated its history for a millennium.

The ability of all these countries to survive the trepidations to which they were subjected once again lays to rest the "environmental" theory of the creation and longevity of civilizations, with plagues, warfare and economic turmoil, all failing to destroy the Nordic countries.

There have been three major contributions of the Scandinavian region to White history: the first Germans swept south into Germany out of the reservoir of Indo-European peoples in the north; then the Vikings swept through Europe and colonized England and parts of the continent itself; and then lastly waves of Scandinavians settled large stretches of modern America.

For these reasons alone, an overview of the Scandinavian countries is crucial to an understanding of European history; although the Vikings as a phenomena deserve special mention by themselves, and are dealt with in the next chapter.

DENMARK

Denmark has some of the finest megalith and other stone age structures in Northern Europe outside of Stonehenge itself, indicators of an advanced early Neolithic civilization in the region thousands of years old.

This society continued uninterrupted until the arrival of the Indo-European invaders of around 2000 BC - the invaders ushered in the iron age and by 400 AD advanced fixed settlements had been in existence for several hundred years.

Settled by other Scandinavians who crossed the Baltic Sea, these early inhabitants of Denmark built a number of impressive structures, the remains of which are still to be seen today.

These include a canal, a long bridge and huge ramparts across the neck of Jutland now called the Danevirke. Some of these structures date from at least two hundred years before the age of the Vikings, which is officially deemed to have started around the year 750 AD.

A silver cauldron recovered from Gundestrup, North Jutland, Denmark, from the year 100 BC. The panels round the cauldron are molded with relief half length figures of Celtic gods and goddesses, some holding human figures and others holding beasts. This is an exquisite example of early Scandinavian artwork, quite apart from being a marvelous presentation of early racial types in the region.

INVASION OF ENGLAND

Within 100 years of the first Danish Viking raids having taken place, enough Danes had settled in England to ensure that an entire section of that island fell under their rule (the region was known as the Danelaw), sparking off a long running conflict with the Britons who had been without Roman protection for over 350 years. The Danish king Sweyn I finally conquered all of England in 1013 and 1014, and his son, Canute II, who ruled England from 1016 to 1035, was the character who according to legend, tried to hold back the sea on the English coast.

CHRISTIANITY SPREADS TO DENMARK

Under King Harold Bluetooth in the 10th Century, the Christianization of the Danes was begun, to be completed by Canute II before the end of his reign in 1035. As was the case with many of the first Christians, the new religion was spread more by fear than by actual genuine conversion: after a generation or two of forced conversion however, the culture became established enough to be genuine only because other alternatives were ruthlessly suppressed.

FURTHER EXPANSION

During the late 1100s and early 1200s, the Danes also expanded to the east, conquering their racial cousins, the Balts, and settling the greater part of the southern coastal areas of the Baltic Sea, establishing an empire twice the size of Denmark itself.

CONSTITUTIONAL REFORMS

The Scandinavian countries generally were the first northern European countries to start constitutional reforms in the direction of a more representative form of government and have long been regarded as amongst the most enlightened governments in the world.

In 1282, the Danish King, Eric V, signed a charter making the Danish crown subordinate to law with an assembly of lords, called the Danehof, forming an important part of the administration of the country. Although by modern standards this hardly meant democracy, for 13th Century Europe it was virtually revolutionary.

UNION WITH SWEDEN AND NORWAY

In 1380, Denmark and Norway were joined under one king, Olaf II, and after his early death in 1387, his mother, Margaret I, ruled, helping to create the Union of Kalmar, consisting of Sweden, Norway, and Denmark. The addition of Norway to the union meant that Iceland and the Faroe islands - discovered and settled by Viking adventurers - fell under effective Danish control.

From the first union with Denmark, a number of Swedish aristocrats worked ceaselessly for greater independence for Sweden, something which was finally achieved with the breaking of the union 1523.

That year proved particularly traumatic for Denmark: not only was the Danish King, Christian II, driven from the throne, but the country was subject to a large amount of interference from some north German towns, led by Lubeck.

With help from the newly independent Swedes, the Danes drove the Germans out and re-established their own king, the new Christian III. During his reign (1534-1559) Denmark quite peaceably became a Protestant nation.

The Christian Wars which destroyed Germany did not affect Denmark anywhere nearly as badly, despite Christian III's active participation in the Thirty Years War on the side of the Protestants against the Catholics.

SCANDINAVIAN CIVIL WAR

The Scandinavians did however manage to trim their own numbers during the Seven Years' War (1563-1570) and the War of Kalmar (1611-1613), both fought between Denmark and Sweden, mainly over commercial and related political rivalry in the region. Neither of these two wars exacted massive tolls from the belligerents, and ended with Denmark abdicating control of all its Baltic sea possessions except for Norway.

AUTOCRATIC RULE

The Danish defeat after the War of Kalmar caused the country to lose some major markets to Sweden: the nobility, who in terms of the early constitution, formed the administrative corps in Denmark, were blamed. In 1660, the Danish king, Frederick III, with the support of the merchant and middle classes, led a coup against the aristocratic Council of the Realm, resulting in the establishment of a hereditary and absolute monarchy in 1661. More importantly, commoners replaced nobles in the administrative structure.

COLONIAL EXPANSION

In the 18th Century, Denmark colonized Greenland, finding scattered Eskimo peoples living there, but generally leaving them alone to get on with their own business. Greenland remains to this day a Danish possession.

Danish trade in East Asia expanded; and trading companies were established in the West Indies, where Denmark acquired several islands including the Virgin Islands.

Large numbers of Danes - hundreds of thousands - also eventually emigrated to the new lands in America: whole swathes of the then opening Mid West of America were settled by hardy Danes and other Scandinavians and Germans, groups who would form the core of the American Mid West farming communities.

NAPOLEONIC WARS

During the Napoleonic Wars, Denmark became involved in the conflict after attempts to blockade the port of Copenhagen (to prevent trading with France) led to the British twice bombarding Copenhagen itself, in 1801 and 1807.

The English navy also successfully destroyed the Danish navy in a few short encounters - all these events caused Denmark to side with Napoleon - a bad choice as it turned out: when the wars ended in 1814 with Napoleon's defeat, Denmark was forced to cede Helgoland to the British and Norway to Sweden.

CONSTITUTIONAL MONARCHY

When the liberal revolutions of 1840 spread across Europe, the Danish king acceded to many of the demands before serious revolution could brew in his country: in 1849, a new constitution was introduced in terms of which Denmark became a constitutional monarchy with a two chamber parliament.

In 1864, Denmark lost the last of its European continental possessions: the German states of Schleswig-Holstein which were hereditary titles held by the King of Denmark, were taken by Prussia after a war between Prussia, Austria and Denmark.

Denmark settled down to a period of prosperity and peace, with a new constitution being introduced in 1901 which carried all the hallmarks of a modern democracy.

Wisely remaining neutral during the First World War (1914- 1918) Denmark avoided any great loss of life or population which dealt serious blows to other continental European countries such as France, Russia and Germany.

In 1917, the Danish West Indian possession of the Virgin Islands was sold to the United States of America, and the independence of Iceland - which had been substantially settled by Scandinavians - was recognized, although full independence would only come to that island in 1944 after a referendum there produced a majority in favor of independence.

In 1920, North Schleswig was incorporated into Denmark as a result of a plebiscite carried out in accordance with the terms of the Treaty of Versailles; the southern part of Schleswig had voted to remain in Germany.

WORLD WAR II (1939-1945)

Denmark also tried to stay out of World War Two, but was overrun in April 1940 by the Germans who passed through the country in their haste to invade Norway. Germany did not treat Denmark as a belligerent country, and allowed the vast majority of the country's legal and domestic administration to carry on as before the German invasion.

Britain occupied the Faroe Islands, and in 1941 the United States established a temporary protectorate over Greenland, which was returned to Danish rule after the end of the war. Greenland was granted home rule by the Danes in 1979. The German occupiers of Denmark were never militarily challenged: they were ordered to surrender at the time of the conclusion of the war in Europe.

IMMIGRATION

Along with her Scandinavian neighbors, Denmark became the focus for substantial amounts of Nonwhite immigration in the last quarter of the 20th Century. This development and its implications are discussed in a separate chapter.

SWEDEN

Sweden had, like the rest of Scandinavia, became an Indo-European Nordic heartland soon after those tribes had entered Europe during their great migrations. In northern Europe, and in Scandinavia particularly, the Indo-Europeans found mostly the Proto-Nordic sub racial types, and soon absorbed these peoples, leaving only scattered traces of this original sub-race to be found today in isolated regions.

The most famous of these Indo-European tribes to settle in what was to become southern Sweden were a sub branch of the Goths, who determined much of the character of that country. The names of many settlements in Sweden reveal the Gothic influence, with the aptly named town of Gothenburg being one of the most prominent examples.

On the Swedish island of Oland are the remains of sixteen ancient Scandinavian stone built forts. These forts had place for living quarters, storage facilities and livestock - evidently they must have been prepared for the occasional siege. Such wars were a feature of early Scandinavian life, caused partially by the geographic isolation of the communities and the individualistic nature of the people themselves.

VIKING EXPANSION

The Swedes were to produce their own set of feared Vikings, who from around 800 AD onwards, established major colonies in what became Russia (the Scandinavian tribe called the Rus gave their name to that country) and other regions in eastern Europe, playing a not insignificant role in populating vast regions of the eastern European continent with Nordic racial sub-types.

CHRISTIANITY

By 850 AD, the first Christian Frankish missionaries had arrived in Sweden to convert the pagan Swedes to the new Jewish originated religion, Christianity. They achieved some success with the conversion of the Swedish King Olaf, and slowly the religion filtered down, displacing the long established Odinism which was the original religion of all the Scandinavians.

During the reign of Eric IX, from 1150 to 1160, the newly Christianized Swedes invaded Finland and forced Christianity by force onto the stubbornly pagan Indo-European tribes in that country. The Swedes were to rule Finland for two centuries as a result.

Eric himself was to die in a Christian setting: he was assassinated by a Danish claimant to his throne while he was attending mass. He was later deified by the church and made patron saint of Sweden.

THE UNION OF KALMAR

By 1389, Swedish nobles had forced the then reigning king to renounce his throne and unify the country with Denmark. Sweden then joined the Union of Kalmar, ruled over by Margaret of Denmark, which incorporated Denmark, Norway and Sweden.

The Danes and the Swedes however never co-existed well: continual skirmishes, mostly of a minor nature, plagued the life of the Union of Kalmar, and in 1520, when it became clear that a rebellion was brewing in Sweden, King Christian II invaded that country and had many of his opponents executed. The large number of executions provoked an uprising: in 1521, a rebellion led by one Gustav Vasa, succeeded and the Union of Kalmar was broken, although Denmark retained the southern part of Sweden. Vasa became King of the Swedes in 1523 as Gustav I and the country officially converted to Protestantism during the 1520s.

EXPANSION

A series of wars and minor conquests saw Sweden steadily expand its territorial size: the Reval district of Estonia voluntarily put itself under Swedish protection in 1561; and in 1582, all of Estonia was added to the Swedish crown after a local Baltic war with Poland.

Sweden's expansion reached a height under Gustav II Adolph, who is still considered by many Swedes to be their greatest king. A war with Russia which ended in 1617, saw Gustav II obtain for Sweden the lands of eastern Karelia and Ingria; a war with Poland from 1621 to 1629, saw Sweden annex all of Livonia and in 1630, Gustav entered the Christian Thirty Year's War on the side of the Protestants in Germany.

At the end of the Thirty Years' War in 1648, Sweden acquired further territories in the Baltic, making it the foremost power in that region.

SWEDEN UNITED

The Swedish king, Charles X Gustav, launched a series of wars with Poland (1655 to 1660) which saw that country completely overrun by the Swedes, forcing the Poles to accept as final the annexation of the territory of Livonia. Charles X also invaded Denmark twice in 1658, resulting in the expulsion of the Danes from southern Sweden. The next Swedish king, Charles XI, made that country an ally of France in the wars of the late 1600s on the continent: as a result the Swedes were beaten by a German army from the state of Brandenburg in 1675.

THE GREAT NORTHERN WAR

The very next Swedish king, Charles XII, at the age of 15, led his country to war against a coalition consisting of Russia, Poland, and Denmark in 1700, in the first phase of what became know as the Great Northern War which lasted for another 21 years.

The Swedes, under Charles XII, successfully invaded north western Russia and decisively defeated the Poles in 1706. The small Sweden could not however hope to resist the relative giant of Russia, and by 1709 the Swedes were routed by the Russians under Peter the Great. This defeat marked the replacement of Sweden by Russia - ironically a state which had for the greatest part been founded by Scandinavians - as the dominant power in the Baltic.

By the treaties of Stockholm and Nystadt in 1721, Sweden lost much of its German territory and ceded Livonia, Estonia, Ingria, part of Karelia, and several important Baltic islands to Russia.

The capture of the town of Malmo by Count Magnus Stenbock. The distinguished Swedish general, Count Magnus Stenbock, took part in the earlier campaigns of the Swedish King Charles XII, and was instrumental in many of the victories, such as this one in 1709 where the Swedes captured the city of Malmo. The Swedes had however, overreached themselves - they could not hope to ward off the relative giant of Russia, and a coalition consisting of Russians, Danes and Saxons, beat the Swedes that same year. Stenbock himself died as a prisoner of war in a Danish prison.

NAPOLEONIC WARS

Sweden joined the Third Coalition (1805) against Napoleon, an alliance which fell apart after Russia deserted it and invaded Finland, forcing Sweden to cede most of that country. The Swedish king of the time, Charles XIII, was childless, and the Swedish parliament, the Riksdag, chose Marshal Jean Baptiste Jules Bernadotte, one of Napoleon's generals, as the crown prince in an attempt to placate Napoleon. The marshal duly became king and established the Bernadotte dynasty, a royal house which Sweden has kept to this day.

Bernadotte however withdrew his allegiance from Napoleon and Sweden fought against France in 1813 and 1814. In terms of the settlement following the end of the Napoleonic Wars, Denmark was forced to cede Norway to Sweden. Norway was to be ruled by Sweden until 1905, when it declared itself independent with Sweden's assent.

EMIGRATION

Despite a benevolent rule under the Bernadottes which saw many constitutional reforms, between 1867 and 1886, nearly half a million Swedes emigrated to America in search of greater liberty and the promise of farming land in the American Mid West.

NEUTRALITY

Sweden retained a strict policy of neutrality right through the major conflicts of the twentieth century, refusing to be drawn into the First or Second World Wars and the Cold War between the Soviet Union and the United States of America.

This image of neutrality was tarnished somewhat by a leftward lurch in Swedish politics in the 1960s; Swedish opposition to the Vietnam War saw that country offering political asylum to many young Americans opposed to that war.

IMMIGRATION

In common with all its Nordic neighbors, Sweden started allowing significant numbers of Nonwhites into its borders during the last quarter of the 20th Century. These changes and their implications are discussed under a separate chapter.

NORWAY

Norway contains some of the oldest White settlement sites in Scandinavia: traces of late Paleolithic settlements dating from 14,000 BC, have been discovered in this region.

The Indo-European invasions of centuries later saw the country being dominated by Nordic sub-racial types, which along with the Proto-Nordics already present in the region, created the "typical Norwegian" blue eyed and blonde look.

By the year 700 AD, some 29 separate tribal kingdoms existed in Norway, with the physical geography of mountains, fjords and rivers encouraging territorial division amongst the tribes.

VIKINGS

The proximity of the sea also encouraged sailing: around 750 AD, Viking raiders were to emerge from Norway and spread out all over Northern Europe, raiding and settling Ireland, Britain, Iceland and the Orkney, Faroe, and Shetland islands. Further expeditions were undertaken which led to the discovery of Greenland and North America.

Equally importantly, bands of Vikings sailed up the major rivers in what was to become Russia, playing a major role in creating that country. Still others settled in France, where they became known as Normans, from "Norse-man."

UNITED NORWAY

Eventually one of the local Norwegian tribal chieftains, King Harold I, called Fairhair, of Vestfold in south east Norway, united the other kingdoms of Norway through diplomacy and conquest. Upon his death in 940 AD, his sons once again divided up the country with (the ghastly named) Eric Bloodaxe as overall king.

The heirs to Harold Fairhair soon set to squabbling amongst themselves and the unity was broken: the Danes and Swedes took advantage of the disunity to make land grabs in Norway itself.

CHRISTIANITY INTRODUCED

Into the dissension of Norway a new ingredient was added: Christianity. In 995, Olaf I, a great-grandson of Harold Fairhair I, became king. Before his accession, Olaf had lived in England, where he had been converted to Christianity. He took the throne with the firm purpose of forcing Christianity on Norway and was partially successful, with his divine mission being interrupted when he was killed in battle with the Danes under King Sweyn I.

Norway was then ruled by Olaf II from 1015, who continued the evangelism of his predecessor, only this time taking the sword to all the pagans who refused to convert to Christianity.

By about 1025, Olaf was more powerful than any previous Norwegian king had been, thereby arousing the hatred of many petty princes who conspired with the Danish/English King, Canute the Great, who, in 1028, managed to drive Olaf into exile into Russia. Two years later Olaf returned and was killed in battle: he was subsequently deified and made into the patron saint of Norway, his blood thirsty activities on behalf of Christianity in that country being ignored.

ICELAND

Upon Canute's death in 1035, his successors united Denmark and Norway through occupation, leading to three centuries of relatively stable home rule for Norway. Iceland was officially added to Norway's territory in 1262, and Norway enjoyed a period of growth and prosperity unequaled in its previous eras, interrupted only by the appearance of the bubonic plague, or Black Death, in the mid 13th Century, a result of which as much as 20 per cent of the population was killed.

The Union of Kalmar was created in 1397 when Norway, Sweden and Denmark were made into a single administrative unit. Norway remained under Danish and Swedish domination for centuries thereafter, although it was granted wide autonomy, particularly after a rebellion brewed in 1815.

INDEPENDENCE

In 1821, the still existing Danish peerage was abolished in Norway and in 1839, the country was granted the right to have its own flag. By 1905, the Norwegians had advanced constitutionally to the point where they declared themselves an independent nation with Sweden's consent.

NEUTRALITY AND OCCUPATION

During the First World War, Norway followed a strict policy of neutrality, a policy which was enforced at the start of the Second World War as well.

However, in April 1940, Britain and France announced that they had mined Norwegian territorial waters to prevent their use by German supply ships. British and German forces then simultaneously invaded the country in an attempt to outflank each other.

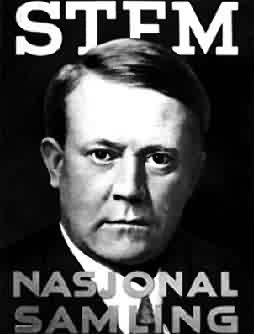

An election poster for Vikdun Quisling, leader of the pro-Nazi National Union party in Norway. Quisling served in the Norwegian embassy in Moscow. Upon his return to Norway he entered politics and became known as a strong anti-Communist, based on what he had seen in the Soviet Union. He was appointed to the Norwegian cabinet in 1931 as Minister of Defense, and in 1933 formed the National Union, with principles based on those of the National Socialists in Germany. When Norway was occupied by Germany in 1940, the National Union was declared the only legal party, and Quisling was appointed prime minister - a position he held until the defeat of Germany in 1945. He was executed by the pro-Allied government in October 1945.

There was considerable support for the German occupation amongst the Norwegians, and several Norwegian army units actively helped the Germans occupy the major ports. The leader of the pro-German forces, Vikdun Quisling, was appointed governor of Norway after the German occupation. Norway remained under German rule until 1945, the armed units there never seeing battle again, being ordered to surrender once the conflict on the continent had been ended. Quisling, who (along with 25 other Norwegians) was executed for his part in the occupational government and a further 50,000 Norwegians were tried for collaboration with the Germans.

MODERN NORWAY

The country recovered well from the trepidations of the war and once again became one of the most economically progressive countries in Europe.

In common with her neighbors, Norway allowed a number of Nonwhites to settle in that country during the last quarter of the 20th Century. The significance of this shift in policy is discussed under a later chapter.

FINLAND

The earliest traces of settlements in Finland date from approximately 8000 BC, the Neolithic Age. These Old Europeans and Proto-Nordics did not make any significant advances until the arrival of the first wave of Indo-European Nordic invaders around 2000 BC, who ushered in the iron age and the first large agricultural settlements.

Due to the relatively large numbers of Old Europeans resident in the region - large compared to the rest of Scandinavia, at least - the resulting mix between Indo-European Nordics and Old European Mediterraneans created a sub racial type which is not as uniformly Nordic in appearance as was the case in Norway or Sweden: to this day there are a far larger proportion of dark haired Finns than what there are dark haired Swedes or Norwegians.

At the same time as the Indo-European invaders, a small tribe of originally Asiatic Finno-Ugric peoples made their way into the country, possibly driven on by the invading Indo-Europeans. These Finno-Urgics formed the Lapp people, nomads of the Arctic circle. Through the addition of large quantities of Indo-European ancestry, many Lapps now display Nordic racial features.

THE SWEDISH CONQUEST

The inhabitants of Finland did not produce any Viking raiders and did not try and form any sort of unified state: it was only with the Christianizing efforts of the Swedes from around 1050 AD that any form of central organization came into being.

The Swedish king, Eric, invaded what was still the unorganized territory of Finland in 1155 with the express aim of converting the Finns to Christianity. Easily defeating the scattered Finnish tribes, Eric then made his evangelical mission - carried out with the by now usual combination of preaching and execution of those unwilling to be converted - into a permanent colony, adding Finland to the Swedish state.

A Christian missionary from England, Henry, who had been preaching at Uppsala in Sweden, also took part in this evangelical mission to Finland: the pagans however killed him in 1156. Henry was later deified by the church and became the patron saint of Finland.

WARS WITH RUSSIA

The rise of the state of Russia on the Finns' eastern border dominated Finnish history for more than one thousand years: the first Russian invasions were carried out by local Russian princes in the late 1200s. When the ruler of Novgorod in Russia invaded Finland for the second time in 1292, the Swedes sent a force into Karelia as far as the Neva River. A treaty of 1323 divided Karelia between Sweden and Novgorod.

When the Union of Kalmar was established in 1397, Finland, as a vassal of Sweden, was automatically drawn into the three way administrative unit. For the next two hundred years Finland remained under effective Swedish control, and many thousands of Swedes settled in that country.

Apart from a running series of wars with Russia, a series of crop failures from in 1695 to 1697 reduced the Finnish population by one fourth. This was followed by the Great Northern War (1700-1721), during which the Russians occupied Finland; at the Peace of Nystadt (1721) it lost large areas in the east, with Russia gobbling up yet more Finnish land after another war in 1741 to 1743.

RUSSIAN RULE, 1809 TO 1917

In 1807, the Russian Tsar, Alexander I, launched an all out assault on Finland, overrunning that country completely by 1809, the year in which it was formally proclaimed as a grand duchy of the Russian Empire. The country was ruled by a Russian governor-general in a newly created capital, Helsinki. During the period of Russian rule, much material and cultural progress was made.

Finland was not directly involved in the First World War, even though Russia was. The Finns, their incipient nationalism awakened during the cultural progress under Russian rule, seized the opportunity afforded by the collapse of Russia after the Communist revolution of 1917 in that country to declare themselves independent in December of that year. Soviet Russia was too weak to resist and Finland became properly independent for the first time.

THE COMMUNIST REVOLUTION CRUSHED

The Finns were however sharply divided along political lines: communists and conservatives faced each other down and formed their own armies, the Red Guards and the White Guards, in imitation of the groupings which were then waging a civil war in Soviet Russia itself. The formation of politically motivated armed units spilled over into violence: the Red Guards reacted violently to a government order to expel all Russian troops, and attempted to launch a Communist revolution in Finland in January 1919, during which Helsinki was seized and a red reign of terror against anti-Communists was launched, during the course of which many civilians were killed.

Backed by German troops, the anti-Communist White Guards, under the leadership of General Carl Mannerheim, recaptured Helsinki and exacted a bitter revenge against the Communists, shooting many out of hand. The Finnish Communist Party was then banned. A republican constitution was implemented and the government was dominated by conservatives.

FRIENDSHIP WITH NAZI GERMANY AGAINST COMMUNISTS

The rise of the Nazi government in Germany and its strong anti-Communist stance was looked on favorably by the Finns. This was reflected by the fact that the Swedish airforce had kept one of its emblems a blue colored swastika.

Although this emblem had been given to the Swedish airforce by a Swedish nobleman who had donated the first Swedish airforce aircraft (with the traditional Indo-European good luck emblem painted on it), the decision to keep the swastika after it had become so strongly associated with the political ideology of Adolf Hitler spoke volumes. Its significance was not lost on the Swedes either - in 1945 they hastily did away with the emblem after Germany's defeat.

Marshal Carl Mannerheim, one of Finland's modern heroes. Born in 1867 in Russian occupied Finland, he joined the Russian army and reached the rank of Lieutenant-General before taking command of the Finnish forces in that country's war of independence against Soviet Russia in 1918. He was instrumental in suppressing the Communist revolution in Finland in 1919, and was regent of that country for seven months in that year. Mannerheim was forced out of retirement to command his country's army in its amazingly successful defense against the Communist Soviet invasion of 1940. He was made President of Finland in 1944, and died in 1951.

A British built Gloster Gladiator, serving in the Finnish Airforce in 1940, with a Finnish emblem of the time: a swastika. Colored blue, the emblem was given to the Swedish airforce in 1919, before the Nazi Party's ascendancy. The decision to keep the emblem after it had become so strongly associated with National Socialism and Adolf Hitler was however an indication of the political leanings of the Finns at the time - indeed they were at that stage involved in a life and death struggle with the Communist Soviet Union, as the Germans would be a short while later.

WORLD WAR II

Although Finland declared its neutrality at the start of the Second World War, the Soviet Union lost no time in invading Finland in November 1939, partly to seize territory, and party as punishment for the suppression of the Finnish communist revolution of 1919.

A bitter winter war followed, with the Finns exacting a disproportionately heavy toll against the Soviet invaders. The Finns, led by General Mannerheim in a new anti-Communist battle, held on grimly in the face of overwhelming odds, but were forced to sue for peace and ceded strips of territory on the border with the Soviet Union.

When the great Soviet-German conflict broke out in 1941, the Soviets bombed Finnish cities due the presence of a small number of German troops in that country. Finland then declared war against the Soviet Union, seizing the advantages gained by the massive German advances into Russia, although it was careful to emphasize that it was not a formal ally of Germany.

In December 1941, Britain then declared war on Finland and the United States broke off diplomatic relations that same month. This move displayed a shocking lack of consistency: Britain and America did not declare war on the Soviet Union when it, without cause, invaded Finland in 1939. After almost three years of exhausting war which saw only minor territorial gains, the Finns dropped out of the war in 1944, ceding further territories to the Soviets in exchange for peace.

MODERN FINLAND

Mainly due to the duplicitous treatment at the hands of the west during the Second World War, Finland maintained a strict policy of neutrality, refusing to be drawn into any post war ideological conflict, only agreeing to participate in, but not join, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) in 1992, after Communism had crumbled of its own accord.

In common with the other Scandinavian countries, Finland opened its borders to a significant number of Nonwhites during the last quarter of the 20th Century. The importance and implications of this development is discussed in another chapter.

or back to

or

All material (c) copyright Ostara Publications, 1999.

Re-use for commercial purposes strictly forbidden.