MARCH OF THE TITANS - A HISTORY OF THE WHITE RACE

CHAPTER 34 : THE TEST OF ETHNICITY - SWITZERLAND, CZECHOSLOVAKIA AND YUGOSLAVIA

Part i - Switzerland and Czechoslovakia

In the first chapter of this book, the difference between race and ethnicity was discussed. "Race" is a collection of individuals sharing a common genetic base; while "ethnicity" refers to the actual cultural manifestations of a particular group of people. Ethnicity is easily transferable amongst members of the same race - only when there are significant racial differences amongst the transferring societies, does the process falter.

This truth of this is perfectly illustrated in the comparative histories of three nations where ethnic conflict has played a major role: Switzerland, the Czech and Slovak Republics, and the former state of Yugoslavia. Switzerland, which retained the highest degree of racial homogeneity, overcame its ethnically based differences with relative ease.

The other two nations - Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia, were however less racially homogeneous than Switzerland, and each therefore only dissolved after conflicts, the intensity and length of which were directly proportional to their homogeneity. The rule is that the higher the racial homogeneity, the more likely there is to be peace amongst racially similar ethnic groupings - the lower the racial homogeneity, the higher the discordance.

In this way the Czechs and the Slovaks entered a period of peace after the German minority were forcibly expelled after 1945, and finally they divided their country peacefully in the 1990s. However the far less racially homogeneous Yugoslavia collapsed into frightful civil war before physical division produced any measure of peace.

SWITZERLAND

ANCIENT SWITZERLAND - ORIGINAL PEOPLE CALLED RHAETIANS

The earliest recorded inhabitants of the country now known as Switzerland were Old Europeans called the Rhaetians, who were related to the Etruscans in Italy. The Rhaetians were, like the Etruscans, overrun by the great wave of Indo-European invaders who swept east and south - the Indo-European tribe who settled in the valleys between the mountains became known as the Helvetti, and this name has stuck to the country ever since.

ROMAN OCCUPATION

Lying directly to the north of Italy, the small land of the Helvetti was overrun by the Roman general Julius Caesar during the 1st Century BC -and the entire region became completely Romanized. It survived as a peaceful Roman province for the next three hundred years.

GERMANIC INVASIONS

Once again thanks to its proximity to northern Italy, the province of Helvetia was overrun by the Germanic invasions which swept over the decaying Roman Empire in the 4th Century AD. Two tribes in particular occupied the region - the Bourguignons and the Alamanni.

None of these invasions affected the basic racial make-up of Switzerland: apart from the original Old Europeans, who had a number of Mediterranean sub-racial types amongst their numbers, all the invaders were Nordic sub-racial elements.

CHRISTIANITY

In common with all the Germanic tribes, the new invaders were pagans, even though the Romanized Helvetti had been introduced to Christianity in the closing years of the Roman Empire.

It was up to the Christianizing Franks under King Charlemagne to introduce Christianity to the Alamanni and the other Germanics in Helvetia - an event which occurred after the Franks invaded the region in the 5th Century AD.

GERMAN RULE

When the Frankish empire dissolved upon Charlemagne's death, most of what became modern Switzerland became incorporated into the duchy of Alemannia, or Swabia, one of the feudal states making up the German Kingdom.

The only part which was not incorporated into the German Empire was acquired in 1033, becoming part of the German Holy Roman Empire.

By 1276, the Austrian House of Habsburg had taken over the crown of the Holy Roman Empire. In 1276, its emperor, Rudolf I, introduced a number of feudal laws and oppressive measures in Switzerland, sparking off ongoing war with the independence minded Swiss which lasted nearly two hundred years.

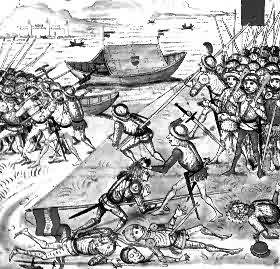

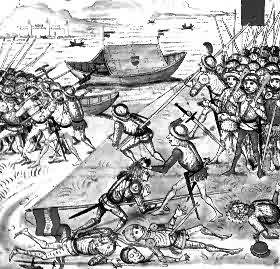

The Swiss struggle for independence against the Austrians - knights in battle, Switzerland, 1474. The Swiss displayed such martial skill during this war that from then on, Swiss mercenaries became the most sought after in Europe - to this day the Pope in Rome recruits Swiss guards as the official soldiers of the Vatican.

INDEPENDENCE - HARD WON BY 1499

By 1474, the Swiss had fought the Austrians to a standstill. In that year, the Swiss regions, by then already known as cantons, were made into a confederation under the loose control of the Habsburgs.

In 1499, the Holy Roman Emperor, Maximilian I, launched an attempt to crush even this hard won autonomy.

A new war broke out between the Swiss and Austrians, resulting in victory for the Swiss. By the Treaty of Basel in 1499, Swiss independence was as good as sealed.

Shortly afterwards some of the last regions in Switzerland then affiliated to the new state in formation.

The Swiss skill in defeating the mighty Austrians led them to become highly regarded soldiers all over Europe - they were recruited as mercenaries by all those who could afford them, including the Pope in Rome, whose Swiss Guards remain to the present day.

ITALIAN ADDITION

While fighting as mercenaries with the French army during the wars of the early 16th Century, Swiss troops annexed some additional parts of northern Italy which became the southernmost canton of Switzerland. The Swiss then tried to take on the French and were unexpectedly badly defeated in 1515.

This defeat caused Switzerland to first adopt a policy of neutrality in all conflicts, one which it has more or less followed ever since, only breaking it to acquire more small territories.

REFORMATION - PROTESTANTS DESTROY CATHOLIC PROPERTY

The Protestant Reformation in Switzerland started in 1518, when a pastor named Huldreich Zwingli denounced the sale of indulgences - forgiveness by God - for money by the Catholic Church. Inflamed by Zwingli's oratory, the people of Zurich rose up and attacked Catholic churches, smashing relics and officially releasing the priests from their vows of celibacy.

Other Swiss towns, such as Basel and Bern, adopted similar religious platforms and in 1536, Geneva, where the French Protestant leader John Calvin had settled, rose up against the duchy of Savoy and refused to acknowledge the authority of its Roman Catholic bishop.

Swiss diplomatic skill prevented the country from becoming involved in the great Christian Wars which resulted from the reformation.

By the end of the Protestant/Catholic Thirty Years' War of 1618 to 1648, Switzerland was once again recognized as a fully independent state by the Treaty of Westphalia which ended that conflict.

NAPOLEON BONAPARTE AND UNIFICATION

The ideals of the French Revolution spread to Switzerland after 1789. Swiss revolutionaries also rose up against the almost feudal system of Lords and Princes who ran the confederation of Swiss cantons. The Swiss revolutionaries were however suppressed by the Swiss nobles, which led to the French revolutionaries sending a French army into Switzerland to help the Swiss revolutionaries.

With French intervention, the Swiss revolutionaries managed to stage a comeback, and a Swiss republic based on the model of the French revolutionary state was established by 1798.

Napoleon Bonaparte then unified the country under the name of the Helvetic Republic, instituting a form of government which proved to be unpopular with the Swiss. In 1803 Napoleon ordered the French occupation troops to leave - although by then a part of Switzerland had been settled by some Frenchmen, creating the French speaking part of Switzerland.

The Congress of Vienna in 1815, which ended the Napoleonic Wars, saw this unpopular constitution rejected and replaced by the former confederal canton system. The Congress of Vienna also made particular note of Swiss neutrality - from that time on the Swiss were never again involved in any foreign war.

INTERNAL CONFLICT SOLVED CONSTITUTIONALLY

The existence of three main language groupings - French, German and a small Italian segment - combined with a split between Protestants and Catholics- made up the classic scenario for an ethnically based conflict. By 1847, the Catholic cantons - mainly German speaking - had formed a united league, the Sonderbund.

The Swiss government declared the Sonderbund illegal in terms of the constitution and ordered them to disband. They refused, and a localized civil war followed, ending in the defeat of the Sonderbund the next year.

The war however caused the Swiss to rethink their constitutional arrangements. In 1874, a new constitution was introduced, which although in some respects tightened up the central government's powers, turned the country into a federal state, giving extraordinary powers to the various cantons to ensure the maximum devolution of power on issues which were likely to cause conflict.

This constitution worked very effectively and is still, with only minor modifications, in use in Switzerland to the present day.

SWISS NEUTRALITY

Apart from their remarkable ability to solve the issue of ethnic conflict, the Swiss are also famous for their steadfast neutrality. Refusing to join the United Nations has ironically made that country ideal "neutral territory" upon which many delicate UN conferences have been held.

IMMIGRATION

Switzerland tightly controls citizenship by biological descent and does not encourage immigration of any sort. However, the country has, like much of Western Europe, been the target of a considerable influx of illegal Third World immigrations. The significance of this Nonwhite immigration into Switzerland is discussed in a later chapter.

THE CZECH AND SLOVAK REPUBLICS

SOME OF THE EARLIEST KNOWN SETTLEMENTS

The region known today as the Czech and Slovak Republics was first occupied by a combination of Proto-Nordic and Old European sub-racial types. These lands, allied with the Bulgarian and other Balkan regions, produced some of the earliest civilizations in the world. Some of the first houses in the world were built in the area, dating from the Upper Paleolithic period - approximately 10,000 BC - some 7000 years before the Mesopotamian civilization.

The settlement of the region by Proto-Nordics and Old Europeans continued peacefully until the arrival of the Indo-European peoples starting around the year 3000 BC, with the region becoming the westernmost point of the area of settlement by the Slav Indo-Europeans.

ROMAN RULE

The Romans incorporated much of the area into their province of Pannonia. The lands were also one of the first to buckle under the Indo-European Gothic invasions, which were followed in quick succession by the Asiatics: Atilla the Hun, the Avar, Bulgar and Magyar invasions; each time being effectively liberated by either Germans, Austrians or combinations of European peoples.

OCCUPATION LEADS TO RACIAL MIXING

The continual occupation of the various regions led to the establishment of defined ethnic groupings - the majority being in sub-racial terms, White, but with a significant minority being of mixed Asiatic-White descent, along with a not inconsiderable overtly Nonwhite "Gypsy" population - who numbered some 500,000 in 1992 - being descendants of Indians who entered Southern Europe at the time of the great Asiatic invasions and who remained biologically isolated from mainstream society.

Each of these White cultural groupings became associated with the various major players in the region: Germans, Austrians, Slavs, with a mix of Slavic and German producing a new ethnic grouping, the Czechs. These territories - Bohemia, Moravia, part of Silesia, Slovakia, and sub-Carpathian Ruthenia, all eventually fell under the control of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

FIRST CZECHOSLOVAK REPUBLIC (1918 - 1938)

The break up of the Austro-Hungarian Empire at the end of the First World War presented an opportunity for a combined leadership core of Czechs and Slovaks to declare independence. The first Republic of Czechoslovakia therefore came into existence in 1918, under the elected presidency of Tomas Masaryk.

The Treaty of Versailles, which ended the First World War, formalized the existence of the Czechoslovakian state. However, the new state became in effect a mini Austro-Hungarian Empire. In the west, millions of Germans in the Sudetenland were included in the new state. In the north a part of historical Poland was added and in the south and east parts of what had been traditionally Hungary were included. All told, the new state contained five ethnic groupings, almost as many as the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

The Czechs made up 51 per cent of the population: Slovaks 16 per cent; Germans 22 per cent; Ruthenes (Ukrainians) six percent; and Hungarians five percent. In addition to these territories, the Czechoslovakian state also inherited the impressive Austrian industrial regions, transforming it overnight into one of the most industrialized nations in Eastern Europe. Austria on the other hand, stripped of its major industrial region, went into serious economic decline.

Tomas Masaryk, 1850 - 1937. The first president of the First Republic of Czechoslovakia was the son of a coachman to the Austro-Hungarian Emperor Franz Joseph. Well educated, he entered the Austro-Hungarian parliament in 1891 and proceeded to fight for the rights of the Slavic minorities within that Empire. When Austria-Hungary went to war in 1914, he fled and eventually found his way to the United States of America, where he enlisted the support of immigrant Czechs and Slovaks and of the US president, Woodrow Wilson, for an independent Czechoslovakia. His efforts paid off when in terms of the peace conference which ended the First World War, Czechoslovakia became an independent nation. The country was however created of many disparate groups - the Czechs made up 51 per cent of the population: Slovaks 16 per cent; Germans 22 per cent; Ruthenes (Ukrainians) six percent; and Hungarians five percent. Masaryk was unable to bind all these nations into one, and upon his retirement in 1935, the different groups had started agitating for independence in earnest. Masaryk died in 1937, and one year later, the first Czechoslovak Republic was dismembered. Slovakia became an independent country, the Germans took German ethnic Sudetenland while Poland and Hungary each took a slice of land. The Czech region became a German protectorate, but was never annexed to Germany. |

ETHNIC PRESSURES

With the rise of nationalist Germany under Adolf Hitler, the three million Sudeten Germans started agitating for inclusion into Germany. At the same time other neighboring countries such as Poland, Bulgaria and Rumania started pressing claims on Czechoslovak territory.

Increasing ethnic tensions, aggravated by the maltreatment of all ethnic minorities by the Czechoslovakian government, gave breeding ground to further nationalist demands. Finally tensions with Germany reached the point where Hitler demanded that the Sudeten Germans be allowed to vote on the issue of re-incorporation with Germany.

MUNICH CONFERENCE 1938

The famous 1938 Munich conference between the major European powers followed: the French and British governments, realizing the increasing seriousness of the situation, prevailed upon the Czechoslovakian government to hand over to the various claiming countries all territories in which the population was in excess of 50 per cent of the respective ethnic grouping: this meant the Sudetenland going to Germany and other smaller parts going to Poland and Hungary.

THE SECOND CZECHOSLOVAKIAN REPUBLIC (1938-1939)

The second, much smaller, Czechoslovakian republic then came into existence. Internally weak, stripped of the (originally Austrian) industrial area, the new state floundered before it started. Taking advantage of the resultant chaos, Germany occupied the regions of Bohemia and Morovia six months after the Munich conference, claiming, with a measure of truth, that the region had originally been German anyway (the first German university had in fact been established in Prague in 1348 by the German Holy Roman Emperor Charles IV). The region was however never formally annexed or added to Germany, merely becoming a protectorate.

Two views of the occupation of Prague by Adolf Hitler in 1939. First, ecstatic German and pro-German Czech and Slovak crowds greet Hitler as he rides into the city which was one of the oldest original German cities; and alongside, not all the Czech minority welcomed the German occupation, as evidenced by these faces in the crowd as German troops drive in. Czech dislike of German rule was however dissipated, and by 1942 had warmed to the idea of German rule. This was the cause of the decision to assassinate the German ruler of the Czech region, Rheinard Heydrich. The Slovaks on the other hand, were overtly pro-German - Slovakia became an independent state nominally under German protection. Slovakia was to lose its independence with the Soviet invasion of 1944, and was only to regain its independence after the fall of Communism.

THE FIRST SLOVAK REPUBLIC (1939 - 1945)

The Slovaks then seized their chance to become independent, and in 1939 the first Slovak Republic came into existence. Pro-German, the region took an active part in the war effort led by the Germans against the Soviet Union. The last territorial division then took place after the Slovaks had declared independence - the region of Ruthenia was returned to Hungary.

Contrary to popular myth then, the dissolution of Czechoslovakia was not a land grab by Germany alone. No less than three countries obtained land from the Czechoslovakian state, and half of Czechoslovakia - Slovakia - became a completely independent state.

It is therefore one of the many distortions about the Second World War to state, as many sources do, that Germany alone demanded the dissolution of Czechoslovakia and occupied the entire country.

GERMAN OCCUPATION - POPULARITY GREW

Welcomed enthusiastically by the Sudeten Germans as liberators, the German army was however met with resentment and in many cases outright hostility by the occupied Czechs.

The German protectorate grew however in popularity over time, particularly after an SS General, Rheinard Heydrich, was appointed governor.

Heydrich's benevolent rule actually caused a dramatic rise in pro-German sympathy amongst the Czechs - so much so that the British government ordered his assassination in Prague in 1942.

The involvement of a few Czechs in Heydrich's assassination led to German reprisals against Czechs, with a number of civilians in the village of Lidice, which was being used as a weapons store by the small Czech resistance movement, being killed in an infamous incident.

The after effect of the reprisals was that the goodwill which Heydrich had built up was dissipated - the British were successful in preventing the Germanization of the Czechs. In August 1944, a small number of anti-German Slovaks tried to overthrow the government of the independent republic of Slovakia - they were however too few and were easily suppressed.

SOVIET OCCUPATION AND THE THIRD CZECHOSLOVAK REPUBLIC (1948-1989)

The defeat of Nazi Germany saw all of Slovakia and the former Czech territories falling under Soviet occupation in 1945. A democratic state was installed, and although the Communist Party won only one third of the votes, the Soviet military occupiers ensured that the Communist Party formed the government.

Ruthenia was ceded to the Soviet Union, and all three million Sudeten Germans were physically driven out of the Sudetenland into Austria and Germany, brutally solving the issue of the German minority literally overnight.

Despite Soviet promises of democracy, Czechoslovakia was quickly turned into yet another Communist one party dictatorship, part of the Warsaw Alliance of Communist nations under the leadership of the Soviet Union.

The Sovietization of Czechoslovakia and the suppression of free enterprise brought about an inevitable economic decline, and by 1968, a part of the Communist Party had realized that reforms were necessary to prevent a total collapse of the state.

THE PRAGUE SPRING - DE-COMMUNIZATION BEGUN

Starting in 1968, the government set about de-sovietizing many aspects of Czechoslovakia. A policy program consisting of major reforms such as the toleration of limited free enterprise; federal independence for the Slovaks - and a more democratically elected government. Central to all these proposed reforms was a loosening of ties with the Soviet Union itself. This period of proposed reform became known as the "Prague Spring".

The Prague Spring ends. An attempt by the Czechoslovakian government to introduce minor reforms was crushed by a massive Communist invasion in August 1968. With armor and half a million troops, the Communists managed to prevent the Czechoslovak state from spinning out of the Communist bloc. Here Czechs confront a Russian armored car crew in the city center of Prague, to no avail.

THE SOVIET INVASION - 1968

Fearing that the reform would spread, the Soviet Union invaded Czechoslovakia in August 1968. Over half a million troops - comprising Russians, Poles, Hungarians and Bulgarians - stormed the borders. Their overwhelming numbers completely suppressed the Prague Spring and the country was quickly put back under a strict Communist government, which abolished all of the intended reform program.

FOURTH CZECHOSLOVAKIAN REPUBLIC (1990-1993)

The fall of Communism in 1989 saw the Communist government in Czechoslovakia collapse. Democratic elections in June 1990 saw a non-Communist government elected. The Slovaks however reasserted their independence and in January 1993, two separate countries - the Czech Republic and Slovakia, were created by mutual consent - a division of territory which was not only peaceful but dramatically different to the conflict which accompanied the dissolution of the Yugoslav state.

IMMIGRATION

Neither the Czech nor Slovakians have ever encouraged immigration from anywhere, and as such, still retain an high degree of racial homogeneity, if the part of the population which shows slight Asiatic ancestry is excluded. The dominant sub-racial types remain therefore Slavic, a combination of Nordic and Alpine sub-racial types.

Click here for part ii : Yugoslavia

or back to

or

All material (c) copyright Ostara Publications, 1999.

Re-use for commercial purposes strictly forbidden.