| |

Brooks refuses polygraph |

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

By

Mark Eddy

Denver Post Staff Writer

April 20 - Brooks Brown walked out of Columbine High School on Tuesday

morning to get a cigarette and instead got a chilling warning from his friend

Eric Harris - moments before the killing rampage began.

"I was walking out for a cigarette and I told him, "Hey, man' and he said,

"Brooks, I like you. Now, get out of here. Go home.' And so I didn't think twice

about it.

"I went to go have my cigarette and heard gunshots, so I took off and started

running. I went to random houses, called the cops and told them I knew who it

was; it was Eric, it had to have been.''

Harris, who was about 5-foot-10, was wearing a white T-shirt and black cargo

pants and was pulling duffel bags out of his car when he told Brown to clear

out. And although police hadn't identified the shooters, Brown said he was sure

Harris and another close friend, Dylan Klebold, apparently attacked and killed

some of their classmates.

"I'm positive he's one of the killers. He had to have been. They said he was

leaving duffel bags all over the place with pipe bombs. He had the white T-shirt

... and he had the bags. I'm just positive it's him. He parked in a spot that he

never parks in, he ditched (school) with this other guy (Klebold) I'm pretty

sure is involved. Oh, my God.''

Brown, his voice cracking, said he'd known Klebold since both were 5.

"The possibility is that one of them ... I am insanely good friends with and

have been since I was 5.'' While Harris had shown signs of violence in the past,

Brown said he thought those days were over.

"For a long time, I would have thought it possible - but not recently - and I

never would have expected this level at all, not even close. And the other

person I think is involved (Klebold), definitely not, not even close.''

Harris, who'd just turned 18, and Brown, also 18, had been friends since they

were sophomores. But the friendship soured a year ago after Harris threw a piece

of ice and broke Brown's windshield, and that's when he showed his dark side,

Brown said. When Brown complained to Harris' parents, Harris threatened to kill

him, Brown said. "He got (mad) at me and told me he was going to kill me.'' He

even went so far as posting a message on his Web site urging anyone who was

interested in killing to hunt down Brown. The family called police three times

but don't know if they acted on the complaint.

But this year the two boys had a couple of classes together and resumed their

friendship, Brown said. "I told him, "Let's bury the hatchet and be friends.' He

said that's cool, he was glad that someone's doing that.''

And while Harris - who with his crewcut looked like a "junior Marine'' - had

been a jerk up until then, after the overture he seemed to turn a corner, Brown

said.

"Recently he's been a lot nicer of a guy. He was a real ---- for a long time,

and then when I told him I wanted to bury the hatchet he just started being cool

to me and just making jokes and being nice,'' Brown said. "He was just an odd,

nice guy, he was kind of nuts for a while, but I mean, the son of a bitch saved

my life basically.'' Some are claiming Harris and Klebold were targeting

minorities, but Brown said that while Harris often made racist comments, he

doesn't think that was the motivation for the shootings.

"He was going after jocks. He hated them with a passion, because they always

made fun of him and they always threatened him. They did it especially his

sophomore year, and he just hated them.''

Harris - who liked to read, write and play video games - talked constantly in

philosophy class of buying a gun, especially since he recently turned 18,

Brown

said. Harris and Brown's other friend were members of the Trench Coat Mafia, a

group of kids who some say were brooding outcasts and misfits. Although Harris

had been nice lately, he was filled with hate and there was only one way for

this shooting rampage to end, Brown said.

"He did it because he hated people. He loved the moment. He loved killing

people, he liked that idea. He lived in that. That's how I knew it would end the

way this did - kill all the hostages and then themselves; I couldn't see

anything else.''

Denver Post staff writer Don Knox contributed to this report.

Copyright 1999 The Denver Post. All rights reserved. This material may not be

published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.

Roth talent

speakers

New Treir speach

Brooks Brown,

a student whom Harris had once been friends with but had later targeted in his

rants, saw Harris entering the school the morning of the massacre, and scolded

Harris for skipping a class.

Harris reportedly said, "Brooks, I like you. Go home." Brooks left the school,

headed for his home which was close to the school. When he learned of the

shootings later, he phoned the police with what he knew.

Brooks Brown

Brooks Brown graduated

from Columbine High

School in 1999; this is his first book. Brooks worked and consulted on Michael

Moore’s Academy Award-winning documentary

Bowling for

Columbine and is

currently working on a documentary of his own. He lives in Littleton, Colorado.

Because of his friendship with Klebold and Harris, and his actions on April

20, Brooks Brown, a tall, rangy and proud member of the high school's outsider

crowd, became one of the most controversial figures to emerge from the crisis

of Columbine. Brown and Harris fell out sometime in 1999, after Brooks'

parents complained to police about Eric's threats against their son, and

Harris put Brooks' name on a "hit list" he maintained on his personal Web

site. But on the morning of April 20,

when Brown encountered Harris headed into the school, locked and loaded,

Harris did not kill him. "Go home, Brooks," Brown recalls Harris saying. "I

like you now."

The first time I saw Brown, a couple of days after the shootings, in the

cafeteria of a hospital near Littleton, he looked like a zombie. Brown had

just left the intensive care unit, where his friend Lance Kirklin was

recovering from multiple gunshot wounds. Much of Lance's face had been shot

off.

Brown's life, too, would soon change forever. On May 4, 1999, Jefferson

County Sheriff John Stone appeared with reporter Dan Abrams on NBC. "I'm

convinced there are more people involved,"

Stone said. "Brooks Brown could be a

possible suspect." Abrams asked about the Harris Web pages. Stone scoffed,

saying these were a "subtle threat," and denied that the Brown family had ever

reported them to the police in the first place.

The Browns interpreted Stone's remarks as an attempt to intimidate them and

shut them up, but they refused to be muzzled. Countless press interviews and

public records requests later came vindication. Documents surfaced that proved

that county sheriff's deputies had indeed visited the Brown home several times

prior to April 20, 1999, to hear their complaints about Eric Harris' Web site.

A chain smoker with green hair, and a devoted fan of the band Insane

Clown Posse, Brown can be found most days in his basement, tinkering with

computers, and acting as webmaster for a couple of youth-oriented Web sites.

He delivered pizzas for Domino's for a month, the only regular job he's held

in the last few years.

One unseasonably warm evening in February, Brown fired up another in a long

series of Camel Turkish Jade Lights and settled into a beanbag chair in the

basement. We ate Chinese food and drank A&W root beer. Brown was still

recovering from six fillings he had earlier in the day, which had required

eight shots of Novocain. That much painkiller, it became clear, hadn't dulled

his anger toward Jefferson County officialdom.

Although his parents harbor some anger at the Klebolds and Harrises, Brown

himself seems not to. In fact, six months after the killings, he says, Brown

drove up to the Klebold home, in the wooded foothills outside Littleton.

Dylan's parents were there. Sue Klebold served Brown some strawberry

shortcake. "I was chilling with Tom and Sue, and we talked about all the

different lies the sheriff was telling, and Tom said,

'You know who would be

great to get out here? Michael Moore.

Go on his Web site -- it has his e-mail. I can't do this because our lawyer

won't let us. But that would be awesome.' I sent Michael Moore an e-mail and

said, 'I'm this kid from Columbine, you might have seen me on the news. I'd

really like to talk to you for a couple of minutes and see if you'd want to

come out and do a movie on Columbine.' So Tom Klebold's the reason 'Bowling

for Columbine' happened."

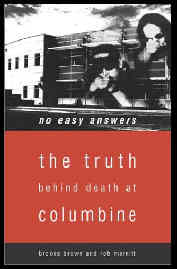

Brown would go on to co-write a thoughtful book, "No Easy Answers: The

Truth Behind Death at Columbine," which describes widespread bullying at the

high school. In a culture of exclusion, loners were singled out for verbal and

physical abuse by a coterie of jocks with a swelled sense of entitlement.

Brown also assisted Moore with his film, some scenes of which were filmed in

and around Littleton. Though Brown admires the film, he feels that Moore

didn't give him enough credit for shooting footage used in the movie. "He or

the people around him are users," says Brown, who says he was promised an

assistant producer credit but received only a simple "thank you."

Columbine became the centerpiece of Brown's life, the driving force behind

a constant battle to defend himself and make the world understand what life

was like inside Columbine High School in the bloody spring of 1999. The usual

post-traumatic conditions presented themselves. Brown struggled with

depression, he says; he'd sleep all day one day, then stay up for three. Empty

bottles of Southern Comfort 100 and Jack Daniels piled up around the house.

"Anything I could get my hands on I would drink and drink and drink." He

recently quit drinking, he says, a sign of his recovery.

"I wrote off a lot of my friends after Columbine, and most of my friends

wrote me off. Immediately after Sheriff Stone said that I was a possible

suspect, a lot of my friends just didn't even want to be seen with me. People

would scream out the window of their car that I was a murderer or they'd tell

me to get out of here before they killed me. And no one wants to be around

that." No evidence of Brown's involvement in the massacre was ever produced,

but that didn't stop Columbine

administrators from banning him from the high school after he graduated in the

spring of 2000. "They thought I was going to kill somebody," he says.

Meanwhile, Brown thinks school officials turned a blind eye to jock-led

bullying, which Brown believes led to the tragedy. "For a year after

Columbine, the administration said there was no bullying at Columbine," he

says. "They just said it never was. Then the governor created a commission

that said there was bullying at Columbine. So they came out and said, 'Well,

we've solved the bullying problem.' That's the brilliant doubletalk they did

for three years, and that was long enough and now no one really pays attention

anymore."

Brown lit another cigarette. "It's like beating your head against a wall,

trying to get things changed. It's painful. It's so stressful and depressing."

Teen targeted by sheriff denies involvement in school attack

By Katherine Vogt

Associated Press

LITTLETON — A classmate who was harassed and threatened by gunman Eric

Harris criticized the sheriff on Wednesday for suggesting that he has withheld

information about the Columbine High School massacre.

"They have no evidence against me. They have nothing. Actually, I know that

the FBI has said that I'm not a suspect. The DA has said that I'm not a

suspect," Brooks Brown said in an interview outside his home.

"Both have said I'm just a witness. I don't know why Sheriff (John) Stone is

doing this. ... I just don't think he's thinking before he talks."

In newspaper and national television show interviews,

Stone has said he believes Brown, 17,

knows more about the April 20 attack at Columbine High School than he has told

investigators.

Brown's parents had earlier criticized Stone for failing to act after they

had told deputies last year that Harris had threatened their son and had written

about bombs and murder on the Internet.

Brown knew Harris, 18, and Dylan

Klebold, 17, and had helped produce a videotape with Klebold.

The day of the shooting, Harris warned Brown to stay away from the school

moments before he and Klebold killed 12 students and a teacher, wounded 23

others and then committed suicide.

Brown and his parents, Randall and Judy Brown, swept aside Stone's suspicions

and said his comments stemmed from their criticism of his department.

"It's incredible; it's wrong," Randall Brown has said. "He should be ashamed

of himself."

Stone was not available for comment, but sheriff's spokesman Steve Davis

reiterated Wednesday that no one has been labeled a suspect, including Brooks

Brown.

Stone retracted an earlier statement after he said three teens detained near

the school on the day of the shooting were suspects. Other officials said the

three had been cleared of involvement.

Investigators said earlier this week they were leaning toward the theory that

Harris and Klebold acted alone, but

Stone said he believes there may have been a third gunman, based on

interviews with student witnesses.

Davis said: "We have had a lot of witnesses tell us there was a third suspect

and we've said that from day one. But, from day one, we've said we hadn't had

any concrete evidence to show that."

Also, Jefferson County Schools Superintendent Jane Hammond said it could cost

$50 million to repair damage to Columbine High School.

In the days after

Columbine,

sheriff's officials openly

inquired about whether

Brooks Brown

might have been involved in the killings.

Harris had told him to go home shortly before the attack.

Judy and Randy Brown don't trust the sheriff's department or the final

report.

The couple had reported Harris to authorities for making threats on a

computer Web site against their son,

Brooks Brown. Because of

that, they question the authenticity of the report's timeline.

"Why does it start at 11:13 a.m.? asked Judy Brown. "Eric started a year

before planning this. He said he was going to do this a year before. He said,

'I'm looking for ground zero.' The police department had that information --

they didn't look into it."

When Harris was about to enter the school just prior to the attack, he

encountered Brooks Brown

and told him to go home. The

Browns said their other son, Aaron, narrowly missed being shot by the attackers.

Mar. 12, 2001

-

Fox News Channel did

viewers no favors Friday, showing

homemade videos of the Columbine High School killers taped by Brooks Brown - a

young neighbor and acquaintance of the shooters - and replaying footage

of Columbine students running with hands over their heads, all while

interviewing Brown via satellite from Denver.

Brown, asked about the meaning and lessons of Columbine, had this to say:

"The whole city of Littleton is based around this weird idea you're supposed to

fear reality" rather than learn lessons from it. "It makes you crazy after a

while."

The casual nature of the discussion, with no serious followup to Brown's

allegations from anchor David Asman, was beneath Denver viewers' expectations in

connection with Columbine.

Brown took the opportunity to chat about the "morality" he shared with the

killers. It was "not based on religion but based in logic and reason."

Huh? We expect this kind of unsupported jabber from talk radio, but

television is supposed to aim a bit higher. It's just another reminder that

24-hour cable news channels really are talk-radio in disguise, with too much

time to fill.

Under the heading "Kids Who Kill," the Fox segment gave plentiful airtime to

Brown's opinion, allowing him to vent what appears to be residual bitterness

toward his town with nothing to promote understanding of the tragedy.

Some people still think Brooks Brown must have been involved. When he goes to

the Dairy Queen, the kid at the drive-through recognizes him and locks all the

doors and windows. Brown knows it is almost impossible to convince people that

the rumors were never true. Like many kids, his life now has its markers: before

Columbine and after.

After the shootings, Stone

publicly questioned whether

Brooks Brown was involved in the plot to attack the school.

There's certainly nothing unusual about that. It's

actually standard FBI procedure to have your son shoot a

training film for a high school

slaughter a couple of years beforehand. It's also standard procedure to

have your other son on hand to eyewitness the crime. Which is why "(Dwayne

Fuselier's) youngest son, Brian, was in the school cafeteria at the time and

managed to escape after seeing one of the bombs explode" (Denver Post,

May 13, 1999).

It should also be noted that another "student who helped

in the production of the film (was)

Brooks Brown" (Associated

Press, May 8, 1999). For those not fortunate enough to be home on the day of

the shooting watching the live cable coverage,

Brooks Brown was the

student enthusiastically granting interviews to anyone who would stick a

microphone in his face.

He claimed to have encountered Harris and Klebold as they

were approaching the school, and to have been warned away by the pair from

entering the campus that day. According to his story, he heeded the warning and

was therefore not present during the shooting spree. Fair enough, but let's try

to put these additional pieces of the puzzle together.

First, we have the son of the lead investigator, who was

obviously a member of the so-called Trenchcoat Mafia, involved in the filming of

a pre-enactment of the crime. Then we have a second son of the lead investigator

being at ground zero of the rampage. And finally we have a close associate of

both the Fuselier brothers and of Harris and Klebold (and a

co-filmmaker) being in the company of

the shooters immediately before they entered the school, this by his own

admission.

And yet, strangely enough, none of them was connected in

any way to the commission of this crime, according to official reports. Not even

Brooks Brown, who should

have, if nothing else, noticed that the pair had some unusually large bulges

under their trench coats on this particular day. At the very least, one would

think that there might be just a little bit of a conflict of interest for the

FBI's lead investigator.

This does not appear to be the case, however, as "FBI

spokesman Gary Gomez said there was "absolutely no discussion" of reassigning

Fuselier, 51, a psychologist, in the wake of the disclosures in Friday's

Denver Rocky Mountain News. "There is no conflict of interest," Gomez said"

(Denver Rocky Mountain News, May 8, 1999). And as no less an authority

than Attorney General Janet Reno has stated: "It has been a textbook case of how

to conduct an investigation, of how to do it the right way" (Denver Post,

April 23, 1999).

So there you have it. There was no conspiracy, there were

no accomplices. It was, as always, the work of a lone gunman (OK, two lone

gunmen in this case). But if there were a wider conspiracy, you may wonder, what

would motivate such an act? What reason could there be for sacrificing fourteen

young lives?

Many right-wingers

would have you believe that such acts are orchestrated - or at the very least

rather cynically exploited - as a pretext for passing further gun-control

legislation. The government wants to scare the people into giving up

their right to bear arms, or so the thinking goes. And there is reason to

believe that this could well be a goal.

It is not, however, the only - or even the primary - goal,

but rather a secondary one at best. The true goal is to further traumatize and

brutalize the American people. This has in fact been a primary goal of the state

for quite some time, dating back at least to the assassination of President John

F. Kennedy on that fateful day in Dallas on November 22, 1963.

The strategy is now (as it was then) to inflict blunt

force trauma on all of American society, and by doing so to destroy any

remaining sense of community and instill in the people deep feelings of fear and

distrust, of hopelessness and despair, of isolation and powerlessness. And the

results have been, it should be stated, rather spectacular.

With each school shooting, and each act of 'domestic

terrorism,' the social fabric of the country is ripped further asunder. The

social contracts that bound us together as a people with common goals, common

dreams, and common aspirations have been shattered. We have been reduced to a

nation of frightened and disempowered individuals, each existing in our own

little sphere of isolation and fear.

And at the same time, we have been desensitized to ever

rising levels of violence in society. This is true of both interpersonal

violence as well as violence by the state, in the form of judicial executions,

spiraling levels of police violence, and the increased militarization of foreign

policy and of America's borders.

We have become, in the words of the late George Orwell, a

society in which "the prevailing mental condition [is] controlled insanity." And

under these conditions, it becomes increasingly difficult for the American

people to fight back against the supreme injustice of 21st century Western

society. Which is, of course, precisely the point.

For a fractured and disillusioned people, unable to find

common cause, do not represent a threat to the rapidly encroaching system of

global fascism. And a population blinded by fear will ultimately turn to 'Big

Brother' to protect them from nonexistent and/or wholly manufactured threats.

As General McArthur stated back in 1957: "Our government

has kept us in a perpetual state of fear ... with the cry of grave national

emergency. Always there has been some terrible evil at home or some monstrous

foreign power that was going to gobble us up if we did not blindly rally behind

it...."

Perhaps this is all just groundless conspiracy theorizing.

The possibility does exist that the carnage at

Columbine High School

unfolded exactly as the official report tells us that it did. And even if that

proves not to be the case, there really is no need to worry. It is all just a

grand illusion, a choreographed reality. Only the death and suffering are real.

Postscript: As the dust settled over

Columbine High, other

high-profile shootings would rock the nation: at schools, in the workplace, in a

church, and - in Southern California's San Fernando Valley - at a Jewish

community center where a gunman quickly identified as Buford Furrow opened fire

on August 10, 1999. The man, who later would claim that his intent was to kill

as many people as possible, had received extensive firearms and paramilitary

training, both from the U.S. military and from militia groups.

Shooting in an enclosed area that was fairly heavily

populated, Furrow fired a reported seventy rounds from his assault rifle. By

design or act of God, no one was killed and only a handful of people were

injured, including three children and a teenager. None of the injuries were

life-threatening and all the victims have fully recovered.

With a massive police dragnet descending on the city,

Furrow fled, abandoning his rolling arsenal of a vehicle. Not far from the crime

scene, he stopped to catch up on some shopping and get a haircut. Along the way,

his aim having improved considerably, Furrow killed a postal worker in a hail of

gunfire, for no better reason than because he was Asian and therefore

"non-white."

At about this same time, Furrow car-jacked a vehicle from

an Asian woman. Though this woman - besides being obviously non-white - was now

a key witness who could place Furrow at the scene and identify the vehicle he

had fled in, she was left shaken but very much alive. Having taken great risks

to obtain her vehicle, Furrow promptly abandoned it, choosing instead to take a

taxi.

In an unlikely turn of events, this taxi would safely

transport Furrow all the way to Las Vegas, Nevada. Having successfully eluded

one of the most massive police dragnets in the city's history (which had the

appearance of a very well-planned training exercise), and having made it across

state lines to relative safety, Furrow proceeded directly to the local FBI

office to turn himself in. No word yet as to whether Dwayne Fuselier was flown

in to head up the investigation.

Meanwhile, in Littleton, Colorado, the death toll

continued to mount. On May 6, 2000, the Los Angeles Times reported that a

Columbine High student

had been found hanged. His death was ruled a suicide, though "Friends were

mystified, saying there were no signs of turmoil in the teenager's life." One

noted that he had "talked to him the night before, and it didn't seem like

anything was wrong."

The young man had been a witness to the shooting death of

teacher Dave Sanders. His was the fourth violent death surrounding

Columbine High in just

over a year since the shootings, bringing the body count to nineteen. Very

little information was released concerning this most recent death, with the

Coroner noting only that: "Some things should remain confidential to the

family." (Los Angeles Times, May 6, 2000)

On February 14, 2000, two fellow

Columbine

students were shot to death in a sandwich shop just a few blocks from the

school. The shootings, which

lacked any clear motive, have yet to be explained. In yet another incident, the

mother of a student who was shot and survived "walked into a pawnshop in

October, asked to see a gun, loaded it and shot herself to death."

(Los Angeles Times, May 6, 2000)

Unexplained was why the shopkeeper would have supplied her

with the ammunition for the gun. Perhaps she brought her own, though if she had

access to ammunition, chances are that she would also have had access to a gun.

Such are the mysteries surrounding the still rising death toll in Littleton,

Colorado.

Editor's note: It is indeed the government's desire to

eliminate the right to keep and bear arms from the American people. The

government has a goal for the American people and needs guns out of our hands to

carry it out. NEVER allow any legislation to pass which will deny the 2nd

Amendment to the Constitution to be destroyed. There's a reason why the framers

placed that right in the Bill of Rights. It's to protect you from the

government. See the first edition of The Journal of

History - (La verdad sobre la democracia) for the demand on child proof

weapons to be manufactured instead of what is being manufactured at the present

time.

Jefferson County Sheriff John Stone

told USA TODAY that he now believes 17-year-old Brooks Brown may be withholding

information from investigators. The sheriff described the student as a potential

suspect or material witness in the case.

"I believe Mr. Brown knows a lot more than he has been willing to share with

us," Stone said in an interview. "He's had a long-term involvement with (Eric)

Harris and (partner Dylan) Klebold, and he was the only student warned to stay

away from the school on the day of the shooting."

Brown has said he was confronted by Harris minutes before the shooting started

and advised to leave the campus.

Brown's father, Randall Brown, responded angrily to Stone's remarks. He strongly

questioned Stone's motives in light of the family's criticism that the

department failed to respond to their complaints a year ago that Harris

threatened their son and bragged on the Internet of his violent intentions.

Harris used his Internet site to write extensively about his bomb-making

activities.

The Browns downloaded those writings and turned them over to the Sheriff's

Department.

"The only person who says (Brooks) is a suspect is this idiot sheriff," Brown

said in an interview. "Brooks is the one who turned this (Harris) kid in in the

first place. He's just trying to protect . . . his department from getting sued.

He's a loose cannon."

Stone has come under fire for making statements that his spokesman later had to

retract, including one in which he said that three teens arrested near the

school on the day of the shooting were suspects, when, in fact, they had been

cleared of any involvement.

So strained is the relationship with the Browns that all law enforcement

contacts with the family have been assigned to the FBI, authorities said. The

FBI had no comment.

"If Brooks had any knowledge at all,

would he have sent Eric (Harris) in to shoot his brother?" the elder Brown said,

referring to Aaron, who was in the school cafeteria when the attack began.

Stone said the family's past complaints have had no bearing on his suspicions.

When Harris was about to enter the school just prior to the attack, he

encountered Brooks Brown and told him to go home. The Browns said their other son,

Aaron, narrowly missed being shot by the attackers.

In the days

after Columbine,

sheriff's officials openly inquired about whether

Brooks Brown

might have been involved in the killings. Harris had told him to go home shortly

before the attack.

Jefferson County Sheriff John Stone

has identified one of Dylan Klebold's classmates,

Brooks Brown, as a possible suspect

in the Columbine High School massacre

that left 13 people. Harris

saw Brown outside the school moments before the attack and warned him to stay

away.

Brown has repeatedly denied involvement, noting his brother was in the

cafeteria when the shooting happened

Meanwhile, Brooks Brown, a classmate who was harassed and threatened by

Harris, criticized Jefferson County Sheriff John Stone Wednesday for suggesting

that he has withheld information about the massacre.

Sure randy, brook's little brother

was in the cafeteria at that time.

At the bottom of page 5 of your son's book it is writen :

" In that instant, i knew something horrible was happening"

I knew I had to get as far away from there as possible".

"I was running to get as far away from CHS"

Hum....was is brother really in the

cafeteria at this moment ???

It doesn't seems...

Since Tuesday's attack, the parents

of Brooks Brown,

a classmate of the suspects, have disclosed that they notified the Jefferson

County Sheriff's Department eight times last year with complaints that Harris, a

neighbor, had threatened their son. The couple, Randy and Judy Brown, said that

after Harris chipped the windshield of their son's car, he created a computer

game that revolved around destroying the Brown house and created a Web site that

featured a death threat against their son and accounts of manufacturing and

exploding pipe bombs.

I applaud

Brooks

Brown for writing this. He

was a longtime close friend of Dylan Klebold and had a like/hate relationship

with Eric Harris (Harris once posted death threats against Brown on his

website). He was also targeted as

a possible "third

suspect,"

though there turned out to

be no evidence supporting this. He gives incredible insight into the

personalities of Harris and Klebold (and Rachel Scott, who he greatly respected.

His writings confirm much of what Scott's parents write).

It should also be noted that another

"student who helped in the

production of the film (was)

Brooks Brown…"

(Associated Press, May 8, 1999). For those not fortunate enough to be home on

the day of the shooting watching the live cable coverage,

Brooks Brown

was the student enthusiastically granting interviews to anyone who would stick a

microphone in his face.

He claimed to have encountered Harris and

Klebold

as they were approaching the school, and to have been warned away by the pair

from entering the campus that day. According to his story, he heeded the warning

and was therefore not present during the shooting spree. Fair enough, but let's

try to put these additional pieces of the puzzle together.

Jefferson County’s head sheriff John

Stone, speaking with firm conviction

in an interview published June 19, 1999, made it decisively clear once

and for all that he is CONVINCED Harris

and Klebold

had accomplices in

the planning and execution of the shooting rampage at

Columbine

High

School April 20.

Harris lets Brown go

| |

|

|

| |

Earlier, Brown said repeatedly

that he encountered Eric Harris entering the school just outside an entrance.

He said clearly that Harris had

given him a break and told him to"get out of there" immediately. Brown

indicates he readily complied.

Yet recently Brooks has said he

was out in the parking lot when

Klebold

and Harris pulled up and saw them

taking bags out of the car. These

"bags" had not been previously mentioned in the version in which Brown

purportedly ran into Harris near a school entrance. It would seem urgent

that these be discrepancies explained.

|

|

| |

|

|

There remain

certain discrepancies in statements made

by Columbine

student Brooks Brown

at various times since the massacre which bear some

hard scrutiny as well.

Brooks Brown,

it must be remembered, was directly

involved in the 1997 video

with the son of the FBI's lead

Columbine

investigator Dwayne Fuselier,

depicting trenchcoated

assassins

slaughtering students at

Columbine

and blowing up the school as a finale.

Earlier, Brown said repeatedly

that he encountered Eric Harris entering

the school just outside an entrance.

He said clearly that Harris had

given him a break and told him to get out of there immediately. Brown

indicates he readily complied.

Yet recently Brooks has said he

was out in the parking lot when

Klebold

and Harris pulled up and saw them

taking bags out of the car. These

"bags" had not been previously mentioned in the version in which Brown

purportedly ran into Harris near a school entrance. It would seem urgent

that these be discrepancies explained.

Brooks Brown’s

tale seems to be taking on some water in a fairly

significant area. There is no intent herein to imply any direct personal

involvement on the part of

Brooks Brown

in the shootings. Yet given the

seriousness of the horror that unfolded that day, the entire situation

must be taken into account, including

Brown’s involvement in the 1997

trenchcoat

massacre video. This makes

Brown's clarification of these

discrepancies all the more critical.

When Eric Harris

walked up to Brooks

Brown in the

Columbine

High School parking lot on April 20, 1999, and told him, "Brooks, I like you

now. Get out of here. Go home,"

Brown's life changed forever. Minutes later, Harris and Brown's close friend

Dylan Klebold murdered 12 students and a teacher. Brown immediately became the

subject of rumor and innuendo, eventually being named as a "potential

suspect"

by the police. Besides the misery of being falsely associated with the murders,

Dressed in

oiled black leather trenchcoats and

carrying duffle bags

containing two 20 pound propane bombs set to go off at 11:17 AM -- during "A"

Lunch, which was when the cafeteria was the most crowded, according to

Eric's notes

-- Klebold

and Harris headed toward the cafeteria. Just outside the west entrance Eric saw

Brooks Brown,

an old friend of both boys. Eric

told Brooks at that time that he liked him now and that Brooks should leave the

school and not come back. Brooks shrugged the cryptic words off and left -

he had already been on his way out, heading home for lunch (he and Eric both

lived within walking distance of

Columbine

High). Brooks was later seen by witnesses, heading south on Pierce Street.

Other inside dope on dope could be

contained in the interviews a

Jeffco investigator conducted

with former Columbine

student Brooks Brown.

I say "could be," because the written record of those interviews is missing --

one of the most glaring omissions from the investigative files. Assistant County

Attorney William Tuthill's

response to a request for the documents was coy: "No report was generated if

there was nothing to report."

Actually, the 11,000 pages of

investigative files released to date contain countless examples of interviews

that generated no new information but were written up anyway.

Brooks Brown

and his parents -- whose ongoing feud with Stone led to a failed effort to

recall the sheriff last year -- say Brooks spent several hours with a

Jeffco

investigator and an FBI agent, answering questions about his friendship with

Klebold

and conflicts with Harris. Other police reports make reference to the statements

Brown gave in those interviews. But the statements themselves are missing.

Brooks Brown

doesn't know what happened to his interviews. He does, however, recall telling

the investigators that somebody ought to check out the Subway shop near the high

school, which had become a haven for drug dealing. Nearly a year after the

massacre, two

Columbine

teens were murdered in that same sandwich shop. The killings remain unsolved,

but speculation that the crime was drug-related continues

The Rohrboughs claim that Taylor's statements to them helps prove that a

Denver SWAT officer fired the fatal bullet that killed their son, who was

fleeing the school during the massacre.

The report makes only brief mention of

Brooks Brown,

a 1999 Columbine

graduate and the only person publicly named by Sheriff John Stone as a possible

suspect. The report does not mention Brown by name but notes that Harris

let one "associate" leave the school prior to the shootings.

None of the eyewitnesses named Brown as one of the colleagues they suspect

was involved.

To adults, Klebold had always come across as the bashful,

nervous type who could not lie very well. Yet he managed to keep his dark side a

secret. "People have no clue," Klebold says on one videotape. But they should

have had. And this is one of the most painful parts of the puzzle, to look back

and see the flashing red lights--especially regarding Harris--that no one paid

attention to. No one except, perhaps, the Brown family.

Brooks Brown

became notorious after the massacre because certain police officers let slip

rumors that he might have somehow been involved. And indeed he was--but

not in the way the police were suggesting. Brown and Harris had had an argument

back in 1998, and Harris had threatened Brown; Klebold also told him that he

should read Harris' website on AOL, and he gave Brooks the Web address.

And there it all was: the dimensions and nicknames of his pipe bombs. The

targets of his wrath. The meaning of his life. "I'm coming for EVERYONE soon and

I WILL be armed to the f___ing teeth and I WILL shoot to kill." He rails against

the people of Denver, "with their rich snobby attitude thinkin they are all high

and mighty...God, I can't wait til I can kill you people. Feel no remorse, no

sense of shame. I don't care if I live or die in the shoot-out. All I want to do

is kill and injure as many of you as I can, especially a few people.

Like Brooks Brown."

The Browns didn't know what to do. "We were talking about our son's life," says

Judy Brown. She and her husband argued heatedly. Randy Brown wanted to call

Harris' father. But Judy didn't think the father would do anything; he hadn't

disciplined his son for throwing an ice ball at the Browns' car. Randy

considered anonymously faxing printouts from the website to Harris' father at

work, but Judy thought it might only provoke Harris to violence. MORE>>

don't propose to know who

Brooks Brown is or what he is made of as a person, but from what I saw

yesterday, he seems to be an

intelligent, articulate, candid yet disenchanted individual. He is writing a

book that will expose what he knows about the

Columbine incident. I

asked him what the reaction will be when people read it, and he said, in effect,

that most people will want to hang him.

He said everyone hates him -- he had

100 friends at

Columbine before the shooting and

now he has none left. Everyone blamed him for the shooting -- they needed

someone to blame. Brooks gave an example. He said when they had a memorial at

Red Rocks they were up on a stage, and DeAngelis was talking about how "everyone

loves everyone" at

Columbine.

Then a quiet chorus of, "Brooks

is a murderer," erupted within the group of students. "Bullshit", said

Brooks, responding to DeAngelis's words.

Brooks made clear his dislike, if not hatred, of Frank DeAngelis. He said if

he were standing in the same room with him he would tear him apart. He said when

DeAngelis appeared before the Review Commission "he played dumb."

Steve Schwietzberger and Brooks talked about two teachers

at Columbine.

Steve said he was trying to get a former student to come forward about what she

knew. He said in 1998 she was in a class with Dylan Klebold. The teacher of the

class, a woman, treated Klebold mercilessly. She would throw him out of the

class and leave the rest of the students in tears. Steve said the student who

saw this, now attending a local college, was reluctant to speak out about it.

Brooks mentioned another teacher, a

man, and if I recall correctly, he was a drama teacher or music teacher. Brooks

said this man was sexist and racist -- he gave some examples. He said the public

image of Columbine

is basically like nothing of what actually goes on inside the school.

Brooks said half the people on the

Review Commission could care less about being there -- the other half are

quietly infuriated at the sheriff's office handling of the investigation and

their refusal to hand over evidence.

At one point, when a group of Jeffco

school officials (not related to

Columbine)

were talking, a couple of the board members started complaining about how Jeffco

won't release any tapes related to

Columbine.

They, like the public, are still in the dark.

I met Judy Brown briefly, but

I did not want to pry any further. Maybe I will see them at the next meeting. I

think they are worn out. Did you know the recall of Sheriff Stone only garnered

a handful of signatures? The Browns ended up submitting two signatures -- both

their own. They kept the few others confidential. No one wanted to sign the

petition.

I hope the Browns continue on. They see this as a cover-up -- the sheriff's

command screwed up, lied, then hid evidence. I believe it is more than that.

I talked with Troy Eid, Chief Counsel to the Governor. He had mentioned in a

line of questioning of Al Preciado that bombs with "mercury switches" were

found. My jaw dropped. At the lunch break I asked him where he had heard that.

He said it may have been mentioned when SWAT members, possibly Bob Armstrong,

testified before the Commission a few months ago. He also said when he was at

Leawood Elementary -- with Governor Owens on April 20th -- they kept hearing

then that the bombs had mercury switches on them. Since the sheriff's office has

never mentioned mercury switches officially before, Eid dismissed it. He took

the official line and swallowed it without question. I see it differently. I

believe this only confirms further that bombs with these switches were found --

advanced military bombs.

There remain certain discrepancies in

statements made by

Columbine

student Brooks Brown

at various times since the massacre which bear

some hard scrutiny as well.

Brooks Brown,

it must be remembered, was

directly involved in the 1997 video

with the son of the FBI's lead

Columbine

investigator Dwayne Fuselier,

depicting trenchcoated

assassins slaughtering students at

Columbine

and blowing up the school

as a finale.

Earlier, Brown said repeatedly that he

encountered Eric Harris entering

the school just outside an entrance. He said clearly that Harris had

given him a break and told him to get out of there immediately. Brown

indicates he readily complied.

Yet recently Brooks has said he was out

in the parking lot when Klebold

and Harris pulled up and saw them taking bags out of the car. These

"bags" had not been previously mentioned in the version in which Brown

purportedly ran into Harris near a school entrance. It would seem urgent

that these be discrepancies explained.

Brooks Brown -- misidentified as a

suspect

Friends with Klebold since first grade, he met Harris in ninth grade.

Though he and Harris clashed at one point -- leading Harris to issue an

Internet death threat -- they later reconciled.

Brown was walking out of

Columbine on April 20, 1999, when he bumped into Harris.

"Get out of here," Harris said. "I

like you."

Brown walked away. Moments later, Harris and Klebold opened fired.

That chance encounter sparked suspicion among sheriff's officials and led to

a long-running feud between Brown and his parents and authorities.

After all, Randy and Judy Brown had reported to sheriff's officers in March

1998 -- a year before

Columbine -- that Eric Harris had threatened their son, that he was talking

about building pipe bombs and committing mass murder.

Nothing happened.

Brown was eventually cleared, but his contempt for authorities has not waned.

"It's pretty upsetting," he said. "I learned a lot of hard lessons in the

last three years."

After graduating, Brown worked several jobs and went to college for a while.

He is writing a book about his

Columbine experience with

a collaborator, and he has helped filmmaker Michael Moore with his upcoming

movie, Bowling for

Columbine.

Though he wasn't physically injured, he was scarred nonetheless.

"It's pretty much all the time, day to day," he said. "It's the kind of thing

that I don't think will ever leave me."

By

Charley Able

Denver Rocky Mountain News Staff Writer

GOLDEN -- The parents of a teen once called a potential suspect

in the Columbine High killings plan to recall Jefferson County Sheriff John

Stone.

Randy and Judy Brown, whose son Brooks was formally cleared of suspicion by

the Sheriff's Office in December, said Wednesday they are in the early stages of

organizing a recall drive.

Judy Brown picked up recall forms from the County Clerk and Recorder's Office

Tuesday.

"We need to get probably 60,000 signatures out of the 300,000 voting public.

That's a daunting task," Randy Brown said. "I believe the people of Jefferson

County voted Sheriff Stone in not knowing who he was. Now they know who he is

and I think they should vote him out."

Stone did not return calls Wednesday seeking comment.

To bring the issue to a vote, the Browns would have to get 41,991 signatures

from registered Jefferson County voters, 25 percent of voters who cast ballots

in the last election for sheriff, said Faye Griffin, Jefferson County Clerk.

Randy Brown said he has set up no organization to guide the recall effort and

has no target date for returning the forms for approval of the petition wording.

"We have not talked to anybody about this. We are still in the planning

stages," he said.

"I hope that people who have been complaining come forward. Certainly the

signatures are there, but now people have to act on it," Judy Brown said. "We

are just going to see what happens and how much help we get."

Once the Browns have the county clerk and recorder's approval on the wording

of the recall petition, they would have 60 days to gather the signatures.

The Browns are setting up a Recall Sheriff Stone Hotline phone number --

(303) 550-1141 -- to facilitate the recall effort.

Randy Brown said he and his wife are initiating the recall drive because of

"a pattern of misrepresentations the sheriff has made regarding Columbine. I

believe it is time to do something.

"I believe he lied to the victims' families about not releasing the

videotapes before they (the families) would view them. ... I believe he lied

about Jefferson County's involvement with Time magazine, and he lied

about my son being a potential suspect."

Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold, who killed 12 of their fellow Columbine

students and a teacher before taking their own lives, made a series of

videotapes in the weeks before the slayings.

Stone allowed a Time magazine reporter to view the tapes. The sheriff

said the reporter promised not to disclose what was on them. But a Time

article published in December included excerpts from the videotapes, prompting

angry reactions from some parents of Columbine victims and other citizens.

The Browns in 1998 provided deputies with pages of violent rantings they had

downloaded from Harris' Web site. Harris also threatened to kill the Browns'

son, Brooks.

Sheriff suspects Brown

In the days following the shooting,

Stone publicly questioned Brooks Brown's relationship with the killers. He

stopped short of calling Brown a suspect but said he was "suspicious" of the

teen.

If the county clerk finds enough of the Browns' signatures are valid, an

election would be scheduled 45-75 days later.

Griffin estimates the cost of a recall election at $250,000, not including

staff time required to validate the signatures.

Contact Charley Able at

(303) 892-5020 or ablec@RockyMountainNews.com..

Brown Polygraph

|

Killers' pal passes polygraph

'Lie-detector' test suggests friend

of Columbine High shooters had no knowledge of impending assault,

parents say

By

Lynn Bartels

Denver Rocky Mountain News Staff Writer

Columbine graduate Brooks Brown passed "lie-detector" test that

indicates he didn't know beforehand about the attack on his school,

his parents say.

Randy and Judy

Brown paid $400 to have their son tested by a polygraph examiner

to try to clear his name.

Jefferson County Sheriff

John Stone has publicly said he is suspicious of Brooks Brown's

relationship with the gunmen who ambushed the school April 20.

"I don't know how much water that test holds, but I'll pass it on

to investigators," sheriff's spokesman Steve Davis said Wednesday.

"If it can be shown that the test was conducted to everyone's

satisfaction, that would be fine. But without knowing the conditions

it was given under, I hate to credit or discredit it."

The test was conducted May 11 by Alverson & Associates, a Denver

polygraph agency. The official results were given to the Browns this

week.

"It is this examiner's opinion that Brooks told the truth to the

best of his knowledge and ... that he did not have any prior

knowledge of the Columbine High School shootings," concluded

examiner David Henigsman.

Brooks Brown was asked the same set of questions four separate

times, and the results were analyzed by a computer, Henigsman said.

He and agency owner Lou Alverson also watched the teen-ager's body

language during the tests.

"He was straightforward. He didn't hem and haw," said Henigsman,

a retired Army counterintelligence officer who has been conducting

polygraph tests since 1975.

The questions included whether Brooks Brown knew beforehand of

the attack, participated in the shootings, bought guns or built pipe

bombs.

Randy and Judy Brown said the report confirmed what they've said

all along: Their son had no idea that his good friends and fellow

seniors Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold planned to destroy their

school.

"Brooks absolutely did not have anything to do with this," Randy

Brown said.

Harris and Klebold killed 12 students and a teacher and wounded

21 others before killing themselves.

Randy Brown said FBI agents and other investigators who

interviewed the family "told us they believed 110 percent in Brooks,

that Brooks was innocent," he said.

But, he said, the FBI claimed that the

sheriff wanted Brooks Brown

to take a polygraph test.

Randy Brown consulted his sister, an attorney in Michigan.

"She said, 'If you do that, you're nuts. There are a thousand

reasons you can fail this, which may have nothing do with telling

the truth,"' he recalled.

Randy and Judy Brown said they were frightened that if the

results were inconclusive -- as can happen with polygraph tests --

the sheriff would try to implicate the teen-ager.

Last month, Stone

outraged the Browns when he linked their son to the shootings.

"Would I rule Brooks Brown out? No," Stone said at the time.

"Would I call him a suspect? No. Am I suspicious of him? Yes."

The Browns believe Stone singled out their son because of their

criticism of how the Sheriff's Department handled a report they made

more than a year before the shootings.

Randy and Judy Brown reported that Harris and Klebold were

building pipe bombs, that Harris had threatened to kill their son

because of an ongoing feud and that Harris' cyberspace rantings were

so violent he should be investigated.

Deputies now say their investigation was limited because the

Browns had asked that investigators not contact Harris' or Klebold's

parents. The Browns said that is untrue, pointing out they have the

families' names, addresses and phone numbers. They said what they

asked was whether their name could be kept out of the investigation.

"I'll tell you what I said about taking a lie-detector test,"

Judy Brown said. "I said, 'Why don't we get in a room with Sheriff

Stone and we can all take a lie-detector test?'

"That's the last time they asked Brooks to take a test."

June 3, 1999 |

|

|

After the shootings, the Browns publicly blasted the sheriff's office for

failing to take their complaints seriously. Stone shot back on the Today

show, describing Harris's online invective as a "subtle threat" that wasn't

prosecutable. Noting that Brooks had told reporters Harris had warned him away

from the school minutes before the attack began, he declared the criticisms a

"smokescreen."

"Brooks Brown could possibly be a

suspect," Stone said. "Mr. Brown, as well as several others, are in the

investigative mode."

The Browns were livid. It was the sheriff who was blowing smoke, they

declared, trying to cover up his agency's incompetence by casting suspicion on

the very people who'd recognized that Eric Harris was dangerous and had tried to

get the cops involved. "Every time we brought up the Web pages, he always

diverted attention to us," Randy Brown says now. "Sheriff Stone had absolutely

no evidence of Brooks being involved. This shows what kind of person he is."

Brooks Brown wasn't the only one to get the Richard Jewell treatment from

Stone and his top brass. The sheriff's off-the-cuff sniping at Harris's parents

undoubtedly contributed to their reluctance to speak with investigators for

months, and his office's willingness to identify other potential suspects by

name, including at least one juvenile, appalled defense attorneys. But Dunaway

says that his boss's terminology was accurate, that there were

plenty of reasons to suspect Brooks.

"This Brown person is telling us that he is in direct personal contact with

Harris moments before the killings begin," Dunaway says. "And Harris tells him

that he likes him and that he should leave the school. Then he shows up in a

class photo with Harris and Klebold, and they're all pointing fingers at the

camera, as if they had guns."

Odd move

The Browns paid for a private

polygraph test to establish that their son had no prior knowledge of the attack;

he passed. But to this day the sheriff's office has never formally cleared

Brooks; Dunaway will only say there's no evidence "at this time" to connect him

to the shootings.

"They're the ones who keep talking

about this stuff," he says of the Browns. "They're

the ones who went to their own polygraphist, but when our investigator asked for

the results and the questions, they refused to give

us any of that information. To say they were cooperative with the investigation

is not correct. They were not cooperative."

"That's a lie," Randy Brown responds. "We spent hours with the police and the

FBI. The only reason they wanted the polygraph results was to try to discredit

them. All these people care about is their own reputation. They don't care about

anyone else at all."

Over the past year the Browns have sought to assemble the paper trail of

their contacts with the sheriff's office, only to find much of it missing or

denied to them. They have been told there's no record of any incident report

stemming from their first complaint about Eric Harris over a broken windshield

(Judy Brown says that deputies contacted the Harrises twice about that

complaint). They have been told that the Browns themselves insisted that the

Harrises not be contacted about the online death threats. (Randy Brown says he

asked that the officers not mention Brooks as the source of the information, for

fear of reprisals, but strongly urged them to contact Eric's father.) They have

been told that John Hicks, the detective assigned to the case, has no record of

meeting with them in his office in March 1998 -- a meeting the Browns recall

vividly because, they say, two bomb technicians gave them a quick lesson in pipe

bombs and Hicks indicated that his office already had a file on Eric Harris.

According to Division Chief John Kiekbusch, many of the "missing" records the

Browns have sought were routinely purged or never existed to begin with. Last

spring the sheriff's office issued a statement confirming that a computer check

in response to the Brown complaints had failed to turn up Harris's prior arrest

for theft; "I cannot verify that a computer check on Harris was done or the

information produced by such a check," Stone says now.

Judy Brown says she has been told she can no longer contact clerks in the

sheriff's office to make public-records requests like any other citizen, but

instead must direct her inquiries to a senior administrator, who hasn't returned

her calls in weeks. "The Browns are free to speak with any sheriff's office

personnel as appropriate to their inquiry or needs," Stone says.

"Our lives have turned into a really bad X-Files," says Brooks Brown.

For Brooks, the burden of being branded a suspect has never entirely gone

away. Students have hissed "murderer" at him on the street and hurled

obscenities from passing cars; even a year later, total strangers feel entitled

to berate him. An avid debater, he recently returned to Columbine to watch his

former team in action, only to be escorted out by a security guard.

"It's been horrible," he says. "I don't think anyone knows how hard it is to

have a best friend that was killed, a really close person like Daniel Mauser,

and you can't go to his parents because they might think you helped kill him. I

was also good friends with Rachel Scott."

After the shootings, the Browns publicly blasted the sheriff's office for

failing to take their complaints seriously. Stone shot back on the Today

show, describing Harris's online invective as a "subtle threat" that wasn't

prosecutable. Noting that Brooks had told reporters Harris had warned him away

from the school minutes before the attack began, he declared the criticisms a

"smokescreen."

"Brooks Brown could possibly be a suspect," Stone said. "Mr. Brown, as well

as several others, are in the investigative mode."

The Browns were livid. It was the sheriff who was blowing smoke, they

declared, trying to cover up his agency's incompetence by casting suspicion on

the very people who'd recognized that Eric Harris was dangerous and had tried to

get the cops involved. "Every time we brought up the Web pages, he always

diverted attention to us," Randy Brown says now. "Sheriff Stone had absolutely

no evidence of Brooks being involved. This shows what kind of person he is."

Brooks Brown wasn't the only one to get the Richard Jewell treatment from

Stone and his top brass. The sheriff's off-the-cuff sniping at Harris's parents

undoubtedly contributed to their reluctance to speak with investigators for

months, and his office's willingness to identify other potential suspects by

name, including at least one juvenile, appalled defense attorneys. But Dunaway

says that his boss's terminology was accurate, that there were plenty of reasons

to suspect Brooks.

To this day

"This Brown person is telling us that he is in direct personal contact with

Harris moments before the killings begin," Dunaway says. "And Harris tells him

that he likes him and that he should leave the school. Then he shows up in a

class photo with Harris and Klebold, and they're all pointing fingers at the

camera, as if they had guns."

The Browns paid for a private polygraph test to establish that their son had

no prior knowledge of the attack; he passed.

But to this day the sheriff's

office has never formally cleared Brooks; Dunaway will only say there's no

evidence "at this time" to connect him to the shootings.

"They're the ones who keep talking about this stuff," he says of the Browns.

"They're the ones who went to their own polygraphist, but when our investigator

asked for the results and the questions, they refused to give us any of that

information. To say they were cooperative with the investigation is not correct.

They were not cooperative."

Just two

Another bomb found

Authorities say suspects may have had

help in planning massacre

By

Matt Sebastian

Camera Staff Writer

U.S. Attorney General Janet Reno implored the surviving students of this

week's Columbine High School massacre to "stand tall" Thursday, saying the

grieving teens "have inspired a nation."

"We cannot and we must not become complacent," Reno said after meeting with

students and victims' families. "We do not have to accept this violence."

With the investigation of Tuesday's schoolyard slaying of 15 people in its

third day, Jefferson County sheriff's

officials more than ever believe that suspects Eric Harris, 18, and Dylan

Klebold, 17, may have had help with their shooting and bombing spree.

"We have no concrete evidence that

more than two were involved," District Attorney Dave Thomas said. "But it is

obvious from the crime scene that it would have been difficult for these two

individuals to do this alone."

That belief grew firmer Thursday morning when investigators found another

unexploded bomb inside the school's kitchen. It was the biggest yet — a device

fashioned from a 20-pound propane tank, a one- or two-gallon gas can and some

wiring.

Had it gone off, sheriff's Sgt. Jim Parr speculated, "It would have been

devastating."

Police say they believe that Harris and Klebold — armed with four guns and a

dozen homemade bombs — walked into Columbine at 11:19 a.m. Tuesday and killed 12

classmates and a teacher before apparently taking their own lives. Twelve more

explosive devices were found in the suspects' vehicles.

Officials said 28 other people were transported to seven area hospitals.

"It is a devastating crime scene," the district attorney said. "My 50 years

on this earth did not prepare me for this. ... I can only describe it as a war

zone."

The question on everyone's lips Thursday remained the same — why? Officials

said they still know no motive for the killing spree, although they confirmed

that some sort of note was found among some paperwork seized from one of the two

suspects.

"I have seen some writings, but I don't know when those were authored,"

Thomas said, characterizing the prose as typewritten and perhaps from a journal.

"I wouldn't necessarily call it a suicide note per se."

Investigators also confirmed that a videotape was seized from the home of one

of the shooters.

Columbine student Ben Oakley said Harris and Klebold last semester made a

film in their video production class showing them "with their fake guns walking

through the halls, shooting jocks."

"Later they animated in the blood," Oakley said. Police wouldn't comment on

the videotape seized this week.

Although police have no firm evidence of accomplices or a third shooter —

whom some witnesses reportedly saw — they say they believe some of Harris and

Klebold's friends may have known of their plans.

"There had been some information exchanged prior to the 20th about what was

going on," Thomas said.

No one has been arrested in connection with the rampage, although some of the

suspects' friends were detained for questioning Tuesday. Police are interviewing

current and former members of the so-called Trench Coat Mafia, the clique that

Harris and Klebold belonged to.

Detectives also have interviewed the parents of both suspects. Sheriff's

spokesman Steve Davis said both sets of parents have been cooperative, although

they have retained attorneys.

The homes of both Klebold and Harris also have been searched. Warrants for

both searches have been sealed by a judge, although a hearing will be held today

to determine whether to keep the documents under wraps.

At the school, 60 to 75 investigators remained in the bullet-scarred building

Thursday, collecting evidence, a process that will last several more days. The

team pulled out about 5 p.m. to rest for the night.

Sheriff's representatives spent much of the day defending their actions, as

questions arose about the timing of the SWAT entry into the occupied school on

Tuesday and the discovery Thursday of another bomb.

"It was not two hours before a SWAT team went in," Davis said, pointing out

that one of his deputies was in the school when the shooting started. Several

other officers responded within three minutes, and the first SWAT team was in

the building in about 20 minutes, Davis said.

Efforts were slowed down by uncertainties about what was happening. A

full-scale SWAT entry didn't occur until about 1 p.m., about a half hour after

the shooting stopped.

"They had no knowledge of how the suspects were, where they were or how they

were dressed," Davis said.

As for the discovery of a new bomb, Barr said the hallways are littered with

hundreds of backpacks — each, to police, possibly carrying an explosive.

"There were 2,000 kids in this school that ran out in a panic," Barr said.

"Some of them ran out of their shoes."

The search for explosives continues slowly, Davis said, and there is no

guarantee investigators won't find more.

On Thursday, students again congregated at Robert F. Clement Park, a few

blocks from the school, to mourn their loss.

"I feel like I need to be here," said Josh Nielsen, 17, a Columbine junior.

"I can't be away from here."

At about 11 a.m., a group of Westminster High School students arrived at the

park, bearing flowers for the several makeshift memorials honoring the dead.

"I didn't know anyone personally from Columbine," student body president Mike

Bredenberger said, "but we can certainly feel for them."

Even professional soldiers were moved by the slaughter. A group of

infantrymen traveled from Ft. Carson on Thursday to pay their respects.

"We feel like we're part of the community, also," Sgt. Rick Jelen said.

Reno's visit provided a morale boost to the dozens of investigators still

processing the massive crime scene, and it was a solace to survivors and the

victims' families.

"She said, 'I'm here to listen to the kids,' " said Mary Sautter, the mother

of a Columbine student, after meeting with the attorney general at the Light of

the World Catholic Church.

Later in the day, Reno appeared at the Jefferson County District Attorney's

Office and pledged to seek an end to school violence. But, she cautioned,

leaders must "shape remedies that fit the facts."

"The cult of violence, I think, is a notion that has come to accept that

violence too often is a way of life."

The attorney general addressed most of her remarks to the students of

Columbine High.

"The first thing you're touched by as you go to a community meeting is the

students' eyes," Reno said. "They're grieving but they're brave. ... They're an

inspiration."

"My message to them is, stand tall."

Camera Staff Writer Jason

Gewirtz contributed to this report.

April 23, 1999

|

Killers' pal passes polygraph

'Lie-detector' test suggests friend

of Columbine High shooters had no knowledge of impending assault,

parents say

By

Lynn Bartels

Denver Rocky Mountain News Staff Writer

Columbine graduate Brooks Brown passed "lie-detector" test that

indicates he didn't know beforehand about the attack on his school,

his parents say.

|

Randy and Judy

Brown paid $400 to have their son tested by a polygraph

examiner to try to clear his name.

Jefferson County

Sheriff John Stone has publicly said he is suspicious of

Brooks Brown's relationship with the gunmen who

ambushed the school April 20.

"I don't know how

much water that test holds, but I'll pass it on to

investigators," sheriff's spokesman Steve Davis said

Wednesday.

|

"If it can be shown that the test was conducted to everyone's

satisfaction, that would be fine. But without knowing the conditions

it was given under, I hate to credit or discredit it."

The test was conducted May 11 by Alverson & Associates, a Denver

polygraph agency. The official results were given to the Browns this

week.

"It is this examiner's opinion that Brooks told the truth to the

best of his knowledge and ... that he did not have any prior

knowledge of the Columbine High School shootings," concluded

examiner David Henigsman.

Brooks Brown was asked the same set of questions four separate

times, and the results were analyzed by a computer, Henigsman said.

He and agency owner Lou Alverson also watched the teen-ager's body

language during the tests.

"He was straightforward. He didn't hem and haw," said Henigsman,

a retired Army counterintelligence officer who has been conducting

polygraph tests since 1975.

The questions included whether Brooks Brown knew beforehand of

the attack, participated in the shootings, bought guns or built pipe

bombs.

Randy and Judy Brown said the report confirmed what they've said

all along: Their son had no idea that his good friends and fellow

seniors Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold planned to destroy their

school.

"Brooks absolutely did not have anything to do with this," Randy

Brown said.

Harris and Klebold killed 12 students and a teacher and wounded

21 others before killing themselves.

Randy Brown said FBI agents and other investigators who

interviewed the family "told us they believed 110 percent in Brooks,

that Brooks was innocent," he said.

Sister

|

But, he said, the

FBI claimed that the sheriff wanted Brooks Brown to take a

polygraph test.

Randy

Brown consulted his sister, an attorney in Michigan.

"She said, 'If you

do that, you're nuts. There are a thousand reasons you can

fail this, which may have nothing do with telling the truth,"'

he recalled.

Randy and Judy

Brown said they were frightened that if the results were

inconclusive -- as can happen with polygraph tests -- the

sheriff would try to implicate the teen-ager.

|

Last month, Stone outraged the Browns when he linked their son to

the shootings.

"Would I rule Brooks Brown out? No," Stone said at the time.

"Would I call him a suspect? No. Am I suspicious of him? Yes."

The Browns believe Stone singled out their son because of their

criticism of how the Sheriff's Department handled a report they made

more than a year before the shootings.

Randy and Judy Brown reported that Harris and Klebold were

building pipe bombs, that Harris had threatened to kill their son

because of an ongoing feud and that Harris' cyberspace rantings were

so violent he should be investigated.

Deputies now say their investigation was limited because the

Browns had asked that investigators not contact Harris' or Klebold's

parents. The Browns said that is untrue, pointing out they have the

families' names, addresses and phone numbers. They said what they

asked was whether their name could be kept out of the investigation.

"I'll tell you what I said about taking a lie-detector test,"

Judy Brown said. "I said, 'Why don't we get in a room with Sheriff

Stone and we can all take a lie-detector test?'

"That's the last time they asked Brooks to take a test." |

|

|

The kids who survived the worst school massacre in U.S. history

have graduated, and some of them have even forgiven. But many of their parents

have not.

By Peter Wilkinson

Because of his friendship with Klebold and Harris, and his actions on April

20, Brooks Brown, a tall, rangy and proud member of the high school's outsider

crowd, became one of the most controversial figures to emerge from the crisis

of Columbine. Brown and Harris fell out sometime in 1999, after Brooks'

parents complained to police about Eric's threats against their son, and

Harris put Brooks' name on a "hit list" he maintained on his personal Web

site. But on the morning of April 20, when Brown encountered Harris headed

into the school, locked and loaded, Harris did not kill him. "Go home,

Brooks," Brown recalls Harris saying. "I like you now."

The first time I saw