UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

SOUTHERN

DISTRICT OF FLORIDA

CASE NO.

01-1859-CIV-SEITZ/BANDSTRA

| Irving Rosner |

Francis Basch |

Veronika Baum |

| Edith Klein Amster |

Peter Drexler |

Erwin Deutch |

| Alice Bessenyey; |

Joseph A. Devenyi |

Michael Fried |

| Elizabet Bleier |

Barauch Epstein |

Magda Feig |

| Paul Gottlieb |

Judith Karmi |

Ethel Klien |

| Mildred Klien |

Tamas May |

David and Irene Mermelstein |

| Edith More |

John J. Rakos |

George Rasko |

| Ana Rosner |

Laslo Sokoly |

Edith Reiner |

| Estate of George Sebok |

Agnes V. Somjen |

Jonas K Stern |

| Olga Steiner |

Irene and Andrew Tibor |

Agnes Valdez |

| Zoltan S Weiss |

and on behalf of

themselves and all others similarly situated. |

| |

Plaintiffs,

v.

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Defendant.

|

|

PLAINTIFFS’ OPPOSITION TO GOVERNMENT’S MOTION TO DISMISS UNDER RULES

12(b)(1) AND 12(b)(6)

I. INTRODUCTION

After three years of litigation, the Defendant again moves to dismiss this

lawsuit brought by Hungarian Holocaust survivors and their heirs. This motion

should be denied, and the Plaintiffs should be allowed to proceed, for the

simple reason that the facts and law plainly compel it.

Notwithstanding the Government’s legal machinations, on key factual questions

little is in dispute. The Government, through its experts and pleadings, now

agrees that the Gold Train contained stolen Jewish property,[1] that it was

handed over to the U.S. with explicit assurance the property would be returned

to Hungary or its rightful owners,[2] that looting and misappropriation

occurred,[3] and that it decided to keep the stolen Jewish property to

alleviate the burdens of the U.S. Treasury.[4] The Government has not

challenged the testimony of Plaintiffs who show their property was on the

train,[5] or the conclusions of Plaintiffs’ expert as to which Jewish

communities in Hungary had their property on the train,[6] or Plaintiffs’

experts who have shown that it was U.S. law and policy to restitute the

property to the country of origin, regardless of later border shifts, and that

Government did so many times.[7] Indeed, before another court, the Government

has made a judicial admission that it was the policy of the United States to

return all property seized in Austria to the country from which it was

taken.[8] The factual differences that do exist (such as the amount of looting

that occurred, the precise dollar value of the property on the train) are

irrelevant at this stage of the proceedings.

The Government’s motion to dismiss is a recitation of irrelevant facts

combined with a series of technical and meritless legal arguments. Indeed,

some of them (e.g., the treaty and other 12(b)(6) defenses) are barred in a

second pre-answer motion under Rule 12(g).

The Plaintiffs’ standing to bring this case is clear. They have suffered an

injury in fact, traceable to the Government’s conduct, and have shown

conclusively that they and other Hungarian Jews had property on the Gold Train

that the United States had in its hands and refused to return. (See infra at §

IV.) The Court already has ruled against the Government twice on the statute

of limitations defense; and Plaintiffs have presented unrefuted evidence that

they did not know about the Gold Train until 1999, or later. (See infra at §

VI.) As for the Government’s rather incredible contention that the survivors

“should have known” the story of the Gold Train, suffice it to say that the

Government’s own expert admits he had never heard of it until the 1980s, and

that years of work in archives were required to learn what happened. (Id.)

The Plaintiffs’ claims for non-monetary relief should proceed. The “military

authority exception” to the APA’s waiver of sovereign immunity does not apply

because the actions complained of are decidedly non-military as alleged

throughout the First Amended Complaint and confirmed through discovery. (See

infra at § VII.) The Government’s 12(b)(6) motion claiming that two

international agreements bar the plaintiffs’ claims (the 1946 Treaty of Peace,

and a 1973 Executive Agreement) are untimely because the Government already

has made a 12(b)(6) motion, and cannot make a second one pre-answer. Even

still, the Government’s argument is specious; neither pact was ever intended

to address victims’ claims. (See infra at §VIII.C.)

Finally, the U.S. Supreme Court’s recent landmark ruling in Rasul v. Bush, 124

S. Ct. 2686 (2004), significantly widens the Court’s authority to hear this

case brought by Hungarian survivors who were friendly aliens during World War

II for alleged violations of the Constitution and international law.[9]

In the end, although the Court may resolve factual disputes when deciding a

Rule 12(b)(1) motion that attacks the facts (as the Government’s motion does),

the law does not permit the court to resolve every fact. Instead, the Eleventh

Circuit requires a court to deal with only the bare minimum, until the court

is satisfied it is competent to exercise its jurisdiction.[10] All facts that

touch on or overlap with the merits must be construed in Plaintiffs’ favor –

to be resolved not merely on cross motion documents, but in a trial.

Since August 2002, when this Court last ruled on the Government’s prior Motion

to Dismiss, the plaintiffs have had the opportunity to conduct limited

discovery. Newly produced documents,[11] combined with court rulings and

admissions by the government,[12] have significantly strengthened the legal

basis for this case. In all, Plaintiffs have more than met the necessary

showing to survive this Motion to Dismiss. They should be permitted to proceed

to trial to test the merits of their case.

II. FACTS

The central fact is this: nearly six decades after the events described, the

defendant through its retained expert, Ronald Zweig, has suddenly admitted

many – in fact, most – of the key factual allegations supporting Plaintiffs’

complaint. The Government’s submission is largely a frontal admission that the

allegations of the First Amended Complaint (“FAC”) are accurate. The

Government has produced few, if any, contemporaneous documents to refute

Plaintiffs’ allegations.

Plaintiffs’ FAC contains the factual allegations that support this case, which

are incorporated herein. In addition, Plaintiffs have submitted expert reports

from Gábor Kádár, Francis A. Gabor, and Jonathan Petropoulos as Exhibits 1, 2,

3, 4, and 5, attached to the Declaration of R. Brent Walton (“Walton Decl.”).

Plaintiffs explicitly rely on and incorporate their statements. It is not

necessary to rely on the Plaintiffs’ experts alone. The Government has

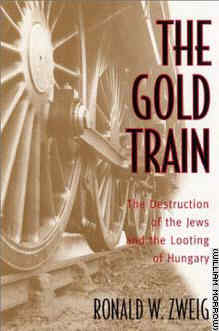

submitted two declarations by Ronald Zweig; the second of which incorporates,

for the first time, his 312-page book, The Gold Train, including its

references (hereinafter “GT”). While Zweig puts a different gloss on the facts

and seeks to justify the Government’s thefts and misappropriations of

property, and its unilateral reinterpretation of the multilateral restitution

agreement, his research confirms Plaintiffs’ case on most major issues. In

addition, the Government put forward as the person most knowledgeable Clayton

Laurie, who gave deposition testimony and [under seal]. While the Government’s

entire motion does not mention the testimony of its “most knowledgeable”

person, his testimony also confirms key aspects the Plaintiffs’ case.

A. The Confiscation of Jewish Property

Plaintiffs assert that a large volume of property stolen from Hungary’s Jews

was loaded onto the Gold Train for plunder. For years, the Government claimed

it did not know what was on the train, or that there was any proof that Jewish

property was on the train. See, e.g., Phillips Dep., 59:6-12, Ex. 14 Walton

Decl. Now, the Government admits the obvious. Zweig states that the Gold Train

“carried a large part of the transportable wealth of the Jews who had lived

within the enlarged borders of wartime Hungary. Gold, wedding rings, watches,

jewelry, silverware, cash, stamp collections, cameras, binoculars, even

Persian carpets and expensive furniture – enough to fill a freight train of

almost fifty wagons.” (GT at 3.) Indeed, the subtitle of his book calls it

“The Second World War’s Most Terrible Robbery.”[13]

Though the parties disagree about the value of the property that was on the

Gold Train, there is no dispute that the Gold Train contained a sizeable

portion of the movable wealth of the Hungarian Jews. Furthermore, there is no

dispute that the cities and towns in Hungary from which the Jewish wealth was

taken and placed on the Gold Train are those specified in Gábor Kádár’s expert

report.[14] Consequently, there is no dispute that the Gold Train contained a

large part of the transportable wealth of the Jews who in 1944 resided in:

Barcs, Bátaszék, Békéscsaba, Beregszász, Beszterce, Budapest, Csíkszereda,

Csorna, Csurgó, Dabas, Debrecen, Dés, Devecser, Diosgyőr, Dombóvár, Eger,

Esztergom, Felsővisó, Gyöngyös, Győr, some places of Heves County, Kaposvár,

Kassa, Keszthely, Kolozsvár, Kunszentmiklós, Marcal, Miskolc, Mohács, Monor,

Mosonmagyaróvár, Munkács, Nagykanizsa, Nagylózs, Nagyvárad, Nyíregyháza,

Orosház, Ózd, Pápa, Pécs, Pécsi, Putnok, Sopron, Sopronkőhida, Sopronkövesd,

Szatmárnémeti, Szécsény, Szentgotthárd, Szigetvár, Szombathely, some places of

Southern Hungary, Tab, parts of the “Transdanubian” region, Tamási, Újpest,

Ungvár, parts of Vas County, Veszprém, Zalaegerszeg, Zalaszentgrót, Zilah, and

Zirc.[15]

B. The Handover of the Train and the Promises Made

The Plaintiffs contend that the train was handed over to the Americans for

safekeeping, at which time a promise was made that the train and its contents

would be returned. Zweig argues that the U.S. promised to return the train;

the Hungarian guards later fretted that while they had indeed received a

promise, it had not been put in writing. (GT at 124; Zweig Dep., 96:20-22.)

The Government admits this fact. (Def. Br. at 9.)

C. Relevant U.S. Rules, Regulations and Policy

The Plaintiffs contend that the policies and laws of the United States

required the Government to restitute the property to Hungary or to Plaintiffs,

the real owners. In its Motion to Dismiss, the Government insists otherwise.

However, in the evidence it has presented, the Government confirms that Decree

No. 3,[16] Provisional Handbook, and the Army Field Manual, are directly

applicable to and governed the Army’s conduct in occupied Austria. First,

Laurie testified at his deposition that the Army is subject to laws and

regulations including the Articles of War, the requirements set forth in the

Army Field Manual, which likewise impose duties and affirmative obligations

upon the Army in occupied Austria. (Laurie Dep., 113:1-5.)[17]

Second, [UNDER SEAL]

Laurie also explained that [UNDER SEAL] Lastly, the Government has also

confirmed and echoed Plaintiffs’ position in statements and arguments it made

to one federal court. Thus, the Government admits that Decree No. 3 governed

the conduct of the occupation forces in Austria, and noted that “[u]nder the

military decrees and policies in effect in post-war Austria, property seized

by the United States Forces in Austria was sorted and turned over to the

country from which the object had been taken.”[18] This Decree required that

all property – “whether stolen, aryanized, or legitimately acquired” – had to

be returned to the country of origin. Id.; see also In re Portrait of Wally,

2002 U.S. Dist. Lexis 6445, *47 (S.D.N.Y. April 12, 2002) (same).

D. Identifiability

Plaintiffs contend that despite classifying the Gold Train as enemy property,

the United States knew from the outset the Gold Train property was “persecutee

property,” that originated from Hungary; and that some considerable number of

individual items were personally identifiable. (See, e.g., FAC at ¶¶ 12, 13,

23, 25, 196, et seq.) The Government cannot prove otherwise.

According to Zweig, the United States knew from the beginning that the Gold

Train contained “persecutee property,” (GT at 124), and confirmed this fact no

later than July 10, 1945, when American Intelligence officials interrogated

the Hungarian soldiers who accompanied the Gold Train. (GT at 123.)[19] Thus,

the Army established that the Gold Train contained looted assets taken from

the Jews of Hungary. Zweig also confirms that the United States never compiled

an inventory (GT at 194; Zweig 1st Rep., at 32); the Government denied

Hungarian requests to create an inventory (GT at 144-145); and refused

requests to inspect the contents from both the Jewish community and the

Hungarian Government (GT at 144, 153.)[20] Moreover, Zweig admits that the

Executive Branch wanted to turn over identifiable items to their proper owners

(GT at 154) and that “items of jewelry” were identifiable. Zweig further

agrees that other items on the train included stamp collections and Judaica, (GT

at 96), both distinctive and thus identifiable.[21] Moreover, the Parke-Bernet

Galleries catalogs of items that the United States caused to be auctioned show

many distinct items, many of which were identifiable.

E. Failure to Safeguard the Property

Zweig confirms that the Government failed to compile a detailed inventory of

the contents on the Gold Train. (GT at 194; Zweig 1st Rep. at 32.) He also

confirms that the United States refused requests from members of the Jewish

community in Hungary and the Hungarian Government to inspect the contents of

the train and assist in inventorying the looted property. (GT at 144-145,

153.) According to one of the documents relied on by the Government and Zweig,

and produced to Plaintiffs, one reason no inventory had been completed was

that the creation of the inventory itself would deprive high ranking members

of the armed forces an opportunity to plunder:

The local American Military Authorities are doing everything to obstruct that

work [inventorying the Gold Train], especially in view of the fact that with

the beginning of this work they have lost a source for easily acquiring

riches. It is known that top-ranking officers of the American Army have

pocketed very valuable items.[22]

F. Hungarian Jews Seek their Property and Are Rebuffed

Zweig confirms that representatives of the Hungarian Jewish community met with

and corresponded with Arthur Schoenfeld, who headed the diplomatic mission to

Hungary, from December 1945 through March of 1946. During that time, they

explained the history of the train and despoliation of the Jews, asked the

Government to inventory the train, asked for the return of the Gold Train, and

offered to help return the property to its owner, and when impossible, the

items would be used for Jewish welfare, and that Hungary had created the

legislative apparatus to accomplish such a purpose. Schoenfeld told them that

they could not make a claim, they needed to speak to the Hungarian Government

about this as the matter was one between the Governments, and that Hungarian

Government was negotiating with the U.S. (GT at 144-145, 153, 158-159; Zweig

Dep., 105-106, 109:26-28, 110:7-14.) Schoenfeld also told them that the Gold

Train was a matter for inter-Allied determination. (Zweig Dep., 110:15-21.)

After being told this, and following Schoenfeld’s instruction, the

representatives approached the Hungarian Government and the Hungarian

Government began to negotiate the return of the Gold Train on behalf the

Jewish community. (Id. 116:5-11.)[23] The Hungarian government even passed a

law that would funnel the looted property back to the original owners and

created a special Jewish committee to help in this process. (Id. 116:12-17; GT

158-159.)

G. Ownership

Zweig concedes that the property continued to belong to the Hungarian Jewish

owners (GT at 106) and that despite the magnitude of the Holocaust there were

approximately 140,000 surviving Jews in Hungary in 1946. (Id. at 140.) His

book weakly explains that the Government decision not to turn the train back

was made because “it was felt” (Id. at 163) that most of the owners had

“presumably” died in Auschwitz (Id.), despite the U.S. knowing about the

presence of a large and vibrant Jewish community in Budapest that repeatedly

sought the return of the items. (Id. at 139-140.)

H. United States’ Mishandling of the Property

Zweig also corroborates Plaintiffs’ allegations of looting and other

mishandling of the Gold Train property while it was in the Government’s

custody. (Zweig 1st Rep. at 32-33.) Although Zweig tries to minimize the

extent to which the Army mishandled the property, he admits that in March of

1946 the United States “formalized” into policy the existing practice of

“allowing officers to requisition materials” solely on memorandum receipt. He

further admits that these items were “rarely returned.” (GT at 155.) In fact,

“almost none” of the items requisitioned were ever returned to Property

Control. (Id. at 198.)

And, though Zweig also tries to minimize the value of the Gold Train and the

looting that occurred while in U.S. custody, he cites and otherwise relies

upon notes of a conversation between Gideon Rafael, envoy for the Jewish

Agency in Palestine, and Col. Arthur Marget, Chief U.S. Economic Officer in

Austria, who not only valued the property between $50 and $120 million in

1945, (Id. at 147),[24] but also informed Rafael – on at least two occasions –

that it was known to him that there was widespread looting.[25] Moreover, the

looting was not confined to senior officers. According to Zweig, “enterprising

young women” were seen wearing jewelry near the Salzburg warehouse. (Zweig 1st

Rep. at 32.)

I. United States’ Determination

Zweig corroborates Plaintiffs’ contention that the United States’ decision not

to return the Gold Train was based on its own budgetary concerns arising out

of its agreement to fund the resettlement of Europeans, including European

Jews. (Zweig 1st Rep. at 36-37; White Decl. at ¶ 22 n.2; FAC ¶¶ 16, 20, 261,

365-66; Plunder & Restitution, at 9, Ex. 16 Walton Decl.) According to Zweig,

the United States unilaterally redefined Article 8 of the Paris Agreement in

two significant ways. (GT at 163-164.) As ratified, Article 8 expressly

applied only to “non-monetary” gold, and then only to the sub-set of

non-monetary gold found in Germany.[26] However, in November of 1946, the

Executive Branch changed the existing and on-going application of Article 8

“so that the original allocation to the IGCR of ‘non-monetary gold found in

Germany’ would be extended to all victim assets (not only gold) found anywhere

in the European theatre, including Austria.” (GT at 163.) Furthermore, Zweig

confirms that the Government made this unilateral amendment to Article 8 of

the Paris Agreement to benefit itself by alleviating the burden on the

Treasury “in connection with the financing and resettlement problems” of

displaced persons (Id. at 167), which was “a problem that would not go away.”

(Id. at 163.)[27] Once these financial benefits to the United States’ fisc

were explained, whatever differences of opinion may have once existed were

gone, the Executive Branch altered Article 8 and “approval [to the decision

not to return the Gold Train property to Hungary] was quickly given.”[28] This

is admitted by the defendant. According to the final report of the

Presidential Advisory Commission on Holocaust Assets, the decision to auction

off the Jews’ property “had the effect of decreasing the financial burden on

the United States of supporting the refugees.” Plunder & Restitution at 9

(emphasis added).

J. Statute of Limitations

Zweig, a noted scholar in the Holocaust and restitution issues stated, that

until the 1980’s, he did not know about the Gold Train. His understanding of

the Gold Train story required research in 25 public and private collections

located in six different countries. Many of the documents are still classified

and some have only recently been released. (GT at x-xi; Zweig 2nd Rep. at 2,

Ex. 8 Walton Decl.)[29]

K. The Sum of the Government’s Admissions Confirms Each Element of Plaintiffs’

Claims

From these admitted facts, it is clear that the United States mishandled the

Gold Train property by: (a) failing to inventory it or maintain property

controls over the inventory; (b) failing to secure the property (which

includes allowing senior officers to “requisition” the property on memorandum

receipt); and (c) by failing to return the property to Hungary. The United

States Government well understood that: (i) the property on the train came

from the Jewish population of Hungary; (ii) numerous items were personally

identifiable[30] and that means existed through the Jewish community by which

even more materials were personally identifiable; (iii) the Government

disposed of the property for reasons that carried out an American budgetary

policy; (iv) and the Government violated its own international agreements and

directly benefited itself. The United States shrouded many of the facts

related to the Gold Train in secrecy for many years, hiding them from the

public view, protecting them by classifications.

These are the major allegations of the Plaintiffs’ complaint. Recognizing its

inability to refute the facts, the Government strains to construct a series of

evasive, legalistic defenses, including a sudden and late “discovery” that not

one, but two international agreements, it now tells the Court, preclude

Plaintiffs’ claims. For the reasons discussed below, all of the Government’s

arguments are incorrect and should be rejected.

legal argument

III. THE COURT MAY NOT DISMISS THE CASE UNDER 12(b)(1)

A. The Government’s Heavy Legal Burden

To obtain a dismissal pre-answer under Rule 12(b)(6)[31] or 12(b)(1), the

Government, being the moving party, bears a heavy burden as “it is a rare case

in which a motion on this ground should be granted.” St. Joseph’s Hosp., Inc.

v. Hospital Corp. of Am., 795 F.2d 948, 953 (11th Cir. 1986). “[A] complaint

should not be dismissed for failure to state a claim unless it appears beyond

a doubt that the plaintiff can prove no set of facts in support of his claim

which would entitle him to relief.” Conley v. Gibson, 355 U.S. 41, 45 (1957);

Roe v. Aware Woman Ctr. for Choice, Inc., 253 F.3d 678, 682 (11th Cir. 2001)

(complaint may not be dismissed unless “it is clear that no relief could be

granted under any set of facts that could be proved consistent with the

allegations”). The Court “must accept the allegations set forth in the

complaint as true.” United States v. Pemco Aeroplex, Inc., 195 F.3d 1234, 1236

(11th Cir. 1999) (en banc).

B. Dismissal Under Rule 12(b)(1) Is Precluded Because Facts Are Intertwined

With The Merits

Though citing to the governing cases in a footnote, (Def. Br. at 16 n.9), the

Government fails to acknowledge that: “it is extremely difficult to dismiss a

claim for lack of subject matter jurisdiction.” Garcia v. Copenhaver, Bell &

Associates, 104 F.3d 1256, 1260 (11th Cir. 1997). [32] Here, the burden is

insurmountable since there are disputed issues of fact intertwined with the

merits; the case cannot be resolved in a motion brought under Rule 12(b)(1).

As the court held in Morrison v. Amway Corp., 323 F.3d 920, 929-30 (11th Cir.

2003), where the jurisdictional challenge requires decision of facts going to

the merits of the case, “the district court should . . . treat[ ] the motion

as a motion for summary judgment under Rule 56 and refrain[ ] from deciding

disputed factual issues”[33] More specifically, the court explained:

If a jurisdictional challenge does implicate the merits of the underlying

claim then ‘the proper course of action for the district court . . . is to

find that jurisdiction exists and deal with the objection as a direct attack

on the merits of the plaintiff’s case. . . . Judicial economy is best promoted

when the existence of a federal right is directly reached and, where no claim

is found to exist, the case is dismissed on the merits. . . . .’ Garcia, 104

F.3d at 1261, quoting Williamson v. Tucker, 645 F.2d 404, 415-16 (5th Cir.

1981). . . .

Id.; see also Lawrence v. Dunbar, 919 F.2d 1525, 1529 (11th Cir. 1990) (same);

5A Wright & Miller, Federal Practice and Procedure § 1350, at 235 (2d ed.

1990).[34]

Thus, although jurisdiction is essential to the exercise of Article III

powers, and even though the Court can resolve certain factual disputes, in

Lawrence and Morrison, the Eleventh Circuit explained that courts should not

decide everything to do with jurisdiction, even in a 12(b)(1) factual attack,

the way the Government requests. Rather, the Eleventh Circuit, consistent with

the requirements of jurisdiction, requires a court to deal with only the bare

minimum, until the court is satisfied that it is competent to exercise its

authority. All findings beyond that are attacks on the merits, not to be

resolved merely on the cross-motion documents, but must await a full trial.

C. Article III Standing For One Party And One Claim Is Sufficient To Confer

Jurisdiction

Article III defines the limits of the “judicial power” – or subject matter

jurisdiction – of the federal courts. This includes the power to hear “all

Cases, in Law and Equity, arising under this Constitution, the Laws of the

United States, and Treaties made or which shall be made, under their

Authority.” Pursuant to this Constitutional authority, Congress has granted

the federal courts jurisdiction over “all civil actions arising under the

Constitution, laws, or treaties of the United States.” 28 U.S.C. § 1331.

Congress has also granted the federal courts jurisdiction over actionable

claims asserted by aliens for “violations of the law of nations or a treaty of

the United States.” 28 U.S.C. § 1350; Sosa v. Alvarez-Machain, infra.

Standing is another threshold issue that must be met before a court can

exercise its Article III powers. However, if “one plaintiff has standing to

bring all claims in an action, the court need not inquire into the standing of

others.” American Iron & Steel Inst. v. OSHA, 182 F.3d 1261, 1274 n.10 (11th

Cir. 1999) (citing Planned Parenthood of the Atlanta Area, Inc. v. Miller, 934

F.2d 1462, 1465 n. 2 (11th Cir.1991)); see also Prado-Steinman v. Bush, 221

F.3d 1266, 1280 (11th Cir. 2000) (one named plaintiff must have standing to

assert the same claims on behalf of other sub-class members).

Similarly, once the Court has jurisdiction over the parties, to obtain

jurisdiction over the case, all the Court needs is jurisdiction over a single

claim. For once the court has jurisdiction over any claim, under the

supplemental jurisdiction provisions of 28 U.S.C. § 1367 and principles

enunciated by the Supreme Court in Supreme Tribe of Ben-Hur v. Cauble, 255

U.S. 356 (1921), the Court may adjudicate the other claims presented, if they

“are so related to the claims in the action within such original jurisdiction

that they form part of the same case or controversy under Article III.” 28

U.S.C. § 1367(a).

D. The Tucker Act Waives Sovereign Immunity

The Government’s dismissal motion all but ignores the issue of sovereign

immunity. However, given a 12(b)(1) motion, Plaintiffs are compelled to

address the issue briefly, as jurisdiction is lacking unless a waiver of

sovereign immunity applies. The Little Tucker Act, 28 U.S.C. § 1346(a)(2),

supplies such waiver and grants the Federal District Court concurrent

jurisdiction with the Federal Court of Claims over “any claim against the

United States founded either upon the Constitution, or any Act of Congress or

any regulation of an executive department, or upon any express or implied

contract with the United States,” as long as the claim does not exceed

$10,000. This language provides a waiver of the Government’s sovereign

immunity, and does so for all claims based on any act of Congress, executive

regulations, implied contracts, and Constitutional claims that can “fairly be

interpreted as mandating compensation” for the damage sustained. United States

v. White Mountain Apache Tribe, 537 U.S. 465, 472 (2003).

This is a new standard, one more relaxed than before:[35]

This “fair interpretation” rule demands a showing demonstrably lower than the

standard for the initial waiver of sovereign immunity. “Because the Tucker Act

supplies a waiver of immunity for claims of this nature, the separate statutes

and regulations need not provide a second waiver of sovereign immunity, nor

need they be construed in the manner appropriate to waivers of sovereign

immunity.” Mitchell II, supra, at 218-219. It is enough, then, that a statute

creating a Tucker Act right be reasonably amenable to the reading that it

mandates a right of recovery in damages. While the premise to a Tucker Act

claim will not be “lightly inferred,” 463 U.S., at 218, a fair inference will

do.

Id. at 472-73. Thus, if a plaintiff relies on an act of Congress, regulation,

or constitutional provision that is “reasonably amenable” to a reading

requiring compensation, then the Tucker Act has waived sovereign immunity and

the suit may proceed. Id.

Furthermore, courts do not strictly construe statutes and substantive rights

against finding a particular right is reasonably amenable to providing

damages. To the contrary, the Supreme Court explained in Mitchell, “the

exemption of the sovereign from suit involves hardship enough where consent

has been withheld. We are not to add to its rigor by refinement of

construction where consent has been announced.” 463 U.S. at 219; see also

White Mountain, 537 U.S. at 477 (rejecting strict requirements in favor of

“the less demanding requirements of fair inference that the law was meant to

provide a damage remedy for breach of a duty”).

Money mandating rights include all statutes that require payment of damages

for violations, breaches of contracts,[36] and breaches of fiduciary duties.

Those rights to compensation can be found in the statute or regulations either

expressly or by implication. Eastport S.S. Corp. v. United States, 372 F.2d

1002, 1007 (Ct. Cl. 1967).

IV. PLAINTIFFS HAVE STANDING

The Government argues that Plaintiffs lack standing because they have suffered

no injury caused by or at least fairly traceable to the actions or omissions

of the defendant that will be redressed by a favorable ruling. (Def. Br. at 17

(citing Lujan v. Defenders of Wildlife, 504 U.S. 555 (1992)). This contention

is amply refuted by the allegations in the FAC, and affirmatively satisfied by

the evidence presented below.

A. Plaintiffs’ Injuries Caused By The Government Can Be Redressed By This

Court

In evaluating whether a party has satisfied Lujan, the Court must “accept as

true all material allegations of the complaint, and must construe the

complaint in favor of the complaining party.” Midrash Sephardi, Inc. v. Town

of Surfside, 366 F.3d 1214, 1223 (11th Cir. 2004) (citing Warth v. Seldin, 422

U.S. 490, 501 (1975)). Moreover, unlike other threshold issues, “a district

court cannot decide disputed factual questions or make findings of credibility

essential to the question of standing on the paper record alone but must hold

an evidentiary hearing,” Bischoff v. Osceola County, 222 F.3d 874, 878, 879

(11th Cir. 2000) (emphasis in original).

Applying these standards here, it is plain that, as alleged, Plaintiffs

suffered a clear and demonstrable injury at the hands of the Government. This

was implicit in the Court’s first ruling denying the Government’s motion to

dismiss. The Government took possession of Plaintiffs’ property and failed to

return it either to them or Hungary despite being required to do so under

implied-in-fact contract theory the Court upheld against the Government’s Rule

12(b)(6) challenge. If the Government had returned the property either to

Plaintiffs or Hungary, Plaintiffs (or Plaintiffs’ now deceased parents or

other loved ones) would have received their property back more than 55 years

ago and would not have had to rebuild their lives from scratch. In fact,

Hungary had enacted a law that required it to return the property to its

owners or pay compensation. (Kádár Dep., 253-254; 261:10-20.) Moreover, the

Government wrongfully retained the Jewish property knowing it was stolen

property to alleviate its own obligations. (Supra at § II.I.) These are

sufficient allegations to establish standing under any circumstance:

Plaintiffs allege an injury to themselves and have a viable claim that would

entitle them to relief by a favorable decision. The threshold issue of

standing is satisfied as a matter of law.

1. Plaintiffs have proved their property was in U.S. custody

The Government contends, without support, that no Plaintiff has demonstrated

his or her property ever came into U.S. possession. (Def. Br. at 18.) By doing

so, the Government ignores the unrefuted evidence offered by Plaintiffs who

have demonstrated that their property came into U.S. possession; some have

done so without the assistance of any expert testimony at all.

For example, Elizabeth Bleier testified that her family’s identifiable

possessions were auctioned off in New York in the late 1940s. She produced

Decree 1600 receipts listing specific property seized by the Hungarians in

April 1944 – property that she was able to identify as having been sold by

Parke-Bernet at auction in 1948,[37] including an elaborate and distinctive

silver bowl;[38] a distinctive piece of jewelry;[39] a handmade handbag;[40]

distinctive hand painted jewelry;[41] and several other specific family

heirlooms seized by the Hungarian Nazis, and auctioned by the Americans. Mrs.

Bleier also produced her own wedding photograph, in which her mother is

wearing a distinctive, handmade brooch that was auctioned off at Parke-Bernet

in 1948.[42] Mrs. Bleier also brought her Kiddush cup (the one depicted in the

FAC at ¶ 468) to the deposition and observed that since the cup had followed a

clear chain of custody—seized from her father, loaded on the Gold Train,

auctioned in New York—it stood to reason that other property seized from her

family at the same time had made the same journey.[43]

The Government does not dispute that property auctioned off at Parke-Bernet

was on the Gold Train, and Zweig confirms that it was. (GT at 206-07.)[44]

Moreover, he corroborates Plaintiffs’ evidence that most of the property sold

at Parke-Bernet auctions held over four years came from the Gold Train. (Id.)

Thus, any Plaintiff who can, as Mrs. Bleier has, identify property in the

auction catalogs as being his or hers has established that his or her property

came into the Government’s possession and was on the Gold Train.[45]

The Government also possesses an inventory of the some 1,200 pieces of art

that came into its possession that the U.S. documents explain were on the Gold

Train.[46] This inventory likewise provides proof that Plaintiffs’ property

was in the Government’s hands. For example, Plaintiff Erwin Deutsch testified

that he and his family were expelled from their apartment in Budapest, and

then stripped of their valuable property (Deutsch Dep., 16:2-5, Ex. 22 Walton

Decl.) He testified that, as documented by witnesses in a 1994 statement a

painting by a well-known Hungarian artist, Fulup Laszlo, was hanging on his

apartment wall. (Id. 21:22-25.) Mr. Deutsch testified that this same painting

was listed in the inventory identifying paintings in the possession of the

United States and stored at the Salzburg Warehouse. (Id. 25:17-21.) Similarly,

Plaintiff Zoltan Weiss identified several paintings from a receipt filled out

by his father, which he believed were likely to be the paintings listed on the

inventory that the Government has determined were on the Gold Train.[47]

2. Expert testimony proves that class members’ property was in U.S. custody.

The Government asserts it is impossible to determine with any degree of

likelihood whose property was on the train. (Def. Br. at 9.) Yet, even beyond

the above examples, any one of which is sufficient to establish standing, the

Government’s assertion is demonstrably wrong. Plaintiffs and their families

turned over identifiable property to the Hungarian fascists, and in turn, that

property was in fact loaded onto the train. (Kádár Aff. at ¶¶ 22-65, Ex. 1

Walton Decl.) If Plaintiffs show “a colorable interest in at least some of the

property,” they are “asserting their own right” and satisfy the standing

requirement. Rodriguez-Aguirre, 264 F.3d 1195, 1206 n.7 (10th Cir. 2001). As

the foregoing examples and the facts below demonstrate, Plaintiffs meet this

test.

Gábor Kádár, Plaintiffs’ expert and recognized worldwide as a leading

authority on the Hungarian Gold Train,[48] has opined after having taken into

consideration the looting that occurred in Hungary, the protocols of the

“processing,” and the separation of Toldy loot from the train, that “when the

United States accepted custody of the Gold Train cargo and acceded to Avar’s

request to safeguard that property until it could be returned to Hungary or

its true owners, the Gold Train contained the stolen Jewish property, from

Jews who resided in the named cities and/or regions identified in Paragraph 65

of Kádár’s Affidavit.[49] Before the Holocaust, the named Plaintiffs (or their

parents or relatives) resided in these places.

Additionally, the Government and Zweig overstate the impact that Toldy’s

separate loot and the alleged “disorganization, massive looting, and the

wartime chaos” had on the train’s cargo. (Def. Br. at 18.) All of these

potential confounding variables were considered carefully by Gábor Kádár in

his opinions. Indeed, both Gábor Kádár and Ronald Zweig have explained that

whatever “disorganization” existed in Hungary, the looting of the valuable

property—the property that was on the Gold Train—was a “carefully organized

plunder.” (GT at 3.)

Second, there is little if any evidence that the wartime chaos had any impact

on the size of the train’s cargo. Certainly, wartime chaos impacted which

Financial Directorates followed the Hungarian protocols and actually delivered

the Jewish property to Budapest or the sorting facilities at Óbánya or

Brennbergbánya. However, there is no evidence of “massive looting” of the

valuable Jewish property intended for the Gold Train. According to official

U.S. documents, there is only one instance where Avar and his men failed to

protect the cargo from looting and theft from the day it left Brennbergbánya

to the day the Army accepted custody over it, and even then only 500

inexpensive chrome-cased watches were lost from the voluminous cargo.[50]

Furthermore, there is little if any documentary evidence of looting in Hungary

either, not even in Zweig’s book—except of course the looting from Plaintiffs

and other Hungarian Jews, and then what Toldy took.[51] Zweig’s evidence of

looting that he describes in his reports are irrelevant to this case, as they

largely address poultry, agricultural products, horses, automobiles, cattle,

equipment, and other property that was never intended for the Gold Train. (Zweig

2nd Rep. at 10 (citing the looting of cattle, farm machinery, animals and

poultry);[52] Zweig Dep., 185-186.) This evidence is unavailing to the

Government’s position, as even Zweig admits its irrelevance to the case:

“[o]nly the most valuable property [looted from the Jews] was selected for

centralization and later transportation out of Hungary,” (Zweig 1st Rep. at 9)

(emphasis added), and the Government has yet to present documentary evidence

that these items were pilfered from the Hungarian authorities handling Jewish

assets once they were under the department’s control, and Kádár has explained

there was very little looting of the valuable movable property because that

property was “safeguarded.” (Kádár Dep., 38-39, Ex. 59 Walton Decl.)[53]

Additionally, the Government is incorrect that the loot taken by Toldy

prevents this case from satisfying Article III. (Def. Br. at 18-19.) It is

relatively easy to remove Toldy from the equation based on the kind of

property he took. For example, he did not take any of 18 cases of gold jewelry

with precious and semi-precious stones (“Ar. eksz”) (GT Inventories at

103-104; Kádár Aff. at ¶ 64, Ex. 1 Walton Decl.; Identification of 18 cases

marked “Eksz,” GT 12394, Ex. 48 Walton Decl.); nor did Toldy have Judaica, (Zweig

Dep., 78:18-22), silver, (Id. 79:6-10),[54] rugs or carpets, (Id. 80:1-4), or

china, (Id. 80:5-6), or other similar property. As Kádár explained in his

affidavit and deposition, Toldy absconded with the small, valuable pieces; he

did not take the silverware, the porcelain, rugs or other household items of

value. (Kádár Aff. ¶ 36; Kádár Dep., 248:5-19.) Toldy’s total take: 44 cases

of valuables identified by Kádár in his affidavit. (Zweig Dep., 77:22-24.)

Thus, for Plaintiffs who are claiming anything other than the kinds of

valuables that traveled in pine cases with the Toldy convoy, whatever

“valuables” Toldy absconded with are irrelevant to the claim.

Plaintiffs lived in the cities and towns[55] from which the loot was taken.

Furthermore, Plaintiffs all provided compelling and undisputed evidence that

the Hungarian Nazis had confiscated their property, some even showing the

Government the receipts given to their families by the Hungarian Nazis under

Decree 1600. These receipts itemize property that was taken, and placed on the

Gold Train.[56] Several Plaintiffs saw their family members take their

family’s property to the local bank as was required. For instance, Plaintiff

Veronika Baum, as a terrified young girl, saw German soldiers go from room to

room in her family’s home and business, inspecting property and taking notes.

(Baum Dep., 47:2-11, Ex. 24 Walton Decl.) Several Plaintiffs had jewelry,

wedding rings and other personal items wrested from them by gendarmes and

soldiers while their families were crowded into the ghetto.[57] The property

seized from these Plaintiffs from the towns identified by Gábor Kádár was

among the property on the Gold Train when the Government accepted custody of

the train.[58]

The Government’s argument, stripped to its essence, is that although the

Government did not own the property on the Gold Train, Plaintiffs have not

proved that they did, thus the property must have been owned by other

Hungarian Jews who lived in the cities and towns listed above but as yet are

unnamed parties to this case and Plaintiffs cannot represent them. The

argument is legally deficient. The Tenth Circuit in Rodriguez-Aguirre, 264

F.3d 1195 (10th Cir. 2001), responded to a similar argument made by the

government and held that the standing requirements were met by those who made

a colorable claim to some of the property. Here, Plaintiffs are asserting

their own rights to the property, they have established that some of their

property was (or at least probably was) on the Gold Train, and that they

certainly have a colorable right to items on the train. (See Zweig Dep.,

101:13-15 (Reasonable to assume that some of the survivors still in Hungary

had property on the Gold Train)). Moreover, under Rule 23, and with the

Court’s permission, Plaintiffs can and have sought to enforce the rights of

all owners of property on the Gold Train. If the class is certified, the Court

would thereby include all property owners that the Government admits exist

but, as yet, are allegedly absent from the case.

3. Plaintiffs’ harm is traceable to the Government’s conduct

Plaintiffs were directly harmed by the Government’s decision not to restitute

their property to Hungary, as U.S. laws and policies required. (Petropoulos

Supp. Aff. ¶¶ 44-50; see Portrait of Wally, at 161-62 (“the United States

Forces were required to transfer all seized property — whether stolen,

aryanized, or legitimately acquired — back to the designated agency of the

country from which the object had been taken”)). The Government contends that

plaintiffs cannot be certain they would have received property or

compensation, had restitution been duly made. (Def. Br. at 19-20.) This is not

a legal defense, but an excuse for misconduct – and a wholly hypothetical one

at that. It provides no basis for dismissal.

The available evidence indicates that the Jews of Hungary would have benefited

from timely restitution. When the United States promised to restitute the

property, Hungary was actively preparing to receive it and to return it to the

Jews. Indeed, in anticipation of the arrival of the Gold Train assets, the

Hungarian Government had formed a Jewish Rehabilitation Agency, in cooperation

with Jewish organizations, and expressly agreed to turn over those assets to

that agency. (See supra at § II.F.) Jewish leaders in Hungary personally

“offered to supervise the return of the items on the train to their individual

owners. Where this was not possible, the items would be used for general

Jewish welfare purposes in Hungary.” (GT at 144.) Weeks later, the Hungarian

Government convened a committee with leaders of the Jewish community to work

together to retrieve the train’s contents. (Id. at 145.) Indeed, Hungary was

willing to assign its claims (and perhaps did assign its claims) to the

Hungarian Jews in an effort to assist them reclaim their property.[59] Later,

when Hungary received its gold reserves, it made clear that it was not waiving

any Jewish claims. (Id. at 156.)

The record is clear: Pre-Communist Hungary, seeking to win favor with the

West, restituted to Jews. (Kádár Aff at ¶ 95, Ex. 1 Walton Decl.) Even the

U.S. knew this: Hungary had adopted several measures “to restore to the Jews

both the status and property of which they were deprived during Hungarian

fascist regimes. In some cases these measures have gone even further than

restoration to include some element of recompense. These measures are all in

conformity with the public statements of Hungarian leaders and the announced

principles of the Hungarian Republic.” (Id. at ¶ 90 (quoting U.S. memo)).

The Government also argues that it would be unfair to have restituted the

property to Hungary, since that nation’s borders had shifted after the war.

(Def. Br. at 20.) Hungary was not unique; the borders of dozens of European

nations changed as a result of World War II. The U.S. was required to

restitute property to the country of origin, without parsing border shifts.

Anything else would have meant either that no property could ever have been

restituted, or the U.S. would have faced an impossible administrative burden.

By April 1944, the U.S. had made clear its conviction that occupation

officials should bear only the initial responsibility for effecting

restitution for property looted from occupied countries, and that “The

question of restoration to individual owners is a matter for these [foreign]

Governments to handle in whatever way they see fit. The original owners may

have received part payment for property taken from them under duress and the

Governments in question may wish to make adjustments for this circumstance in

returning the property. In some cases it may be impossible to locate the

original owners or their heirs and the Governments involved will have to

decide what should be done with the property or proceeds therefrom” (Plunder

and Restitution, SR-140). Thus, once looted assets were returned to the

country of origin, no additional U.S. involvement was deemed necessary or

desirable.

(Petropoulos Supp. Aff. at ¶ 7, Ex. 4 Walton Decl.) (emphasis added); see also

id. at ¶ 63 (“[the United States] restitutes any property irrespective of

ownership [once the officials] are satisfied that removal was by general

direction of ex-enemy puppet government or without compensation, or even

removal by owner himself without compensation as in case of Hungarians”). So

consistent with restitution laws and policy, the United States restituted

property to the U.S.S.R., Poland, Czechoslovakia, Romania, and Hungary, and

others – all countries that saw their borders shift. (Id. at ¶ 5; Petropoulos

Dep., 88-90, Ex. 60 Walton Decl.) In fact, as early as 1945, the Government

began to return parts of the Gold Train — the railcars — to Hungary despite

that some cars bore markings of other countries. (Zweig Dep., 86:11-22.)[60]

The train and its contents came from Hungary. The law required their return to

Hungary. The United States immediately returned some railcars but kept the

contents.

Furthermore, the Government’s recent “unfairness” argument is not supported by

the facts. The wealth of the Hungarian Jews was focused in Hungary, as the

country is known today, and the core of wealth on the Gold Train came from

Budapest. (Kádár Dep., 29:16-17, Ex. 59 Walton Decl.; see also Zwieg Dep.,

49:5-17 (acknowledging wealth focused in Budapest and a few other major urban

areas, and Kruge in Greater Hungary)).

Lastly, to the extent that some Plaintiffs might not be able to prove

conclusively which items of their specific property were on the train, that

failure is itself ascribed to the Government’s unlawful acts. The passage of

decades has made it far more difficult for Plaintiffs – individually or as a

class – to identify specific personal property (though, of course, some are

able to, see supra). For example, the Government was required to inventory and

keep proper records of the property accepted into custody.[61] However, the

Government never did this with the Gold Train. Certain categories of items

were frequently marked with initials or engraved with family names.[62]

Numerous Plaintiffs testified that they would have been able to identify their

property had they been given access to it in a timely manner, viz., in the

years immediately after World War II.[63] Additionally, the Government had in

its possession numerous lists of property and property owners, as well as

sealed envelopes that, according to U.S. documents, bore the names of original

owners. (Kádár Aff. at ¶ 59; Petropoulos Supp. Aff. at ¶ 57.) Those lists,

once in the possession of the Government, now have disappeared and were not

used by the Government in making its decision, even though that was the reason

they were retained. (Kádár Aff. ¶ 59.) Furthermore, the Government on numerous

occasions rebuffed the efforts of representatives of the Hungarian Jewish

community and/or the Hungarian Government to inspect the property, help

inventory the property, or aid the Government in returning the property to its

rightful owners.[64] (See supra at § II.F.)

The doctrine of “spoliation” holds that when a party has within its possession

evidence that is damaged or eliminated, it is appropriate to presume the

evidence was contrary to the interest of the party. In this case, the

Government allowed property and lists of property to be lost, degraded,

destroyed or sold, at a time when it knew full well that claims were being

made by the Hungarian Jews. In 1945-47, representatives of the Hungarian

Jewish community, as well as directly pleading with United States authorities

for access to the property, were pursuing the only legal remedies that the

Government told them were available, namely working through the Government of

Hungary. The Government thus was on notice that claims were being made on the

property, and in fact, knew that after February 1946, the Hungarian Government

had waived its rights to the property in favor of the Jews and was now

asserting the claim for the property on behalf of Hungarian Jews. (See supra.)

The Government was aware that it might face liability for the property in a

court of law. As the transfer of the property to the International Refugee

Organization was being readied, the United States sought indemnification from

the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee (“Joint”) for legal claims

expected to be brought by Hungarian Holocaust survivors. The Joint demurred,

as an internal memorandum concluded that such guarantees might get the group

in “legal hot water.” Joel Fischer, the general counsel to the Joint, wrote:

The U.S. Army is presumably turning over to the IRO all of the non-monetary

gold in Austria, (including the Hungarian Gold Train) which they have and

which has not been stolen by individuals. . . . For us to come forward and

give guarantees with respect to claims which might be lodged against these

assets would be ill advised. We will receive the proceeds from the sale of

these assets without any strings attached and why should we start attaching

strings for ourselves; from your letter I'm sure you'll agree.

Letter from Joel Fischer to Moses Leavitt, Aug. 2, 1947, Ex. 43 Walton Decl.;

see also Memo to Sec. of State from Paris, France sgd Caffery, 3 July 1946, GT

22808-22813 (noting Gen. Tate’s recommendation to set aside a reserve of 15%

to satisfy future claims), Ex. 41 Walton Decl.

The Government cannot shirk its obligations to restitute the stolen Jewish

property because of conjecture that Hungary might shirk its own laws and

treaty obligations. Whether Hungary would have broken its promise to the Jews

is unprovable speculation. That the United States broke its promise to the

Hungarian Jews is proven historical fact.

Plaintiffs meet the threshold requirements required by Article III.

B. This Case May Not Be Dismissed Under the Doctrine of Prudential Standing

1. Prudential standing principles are not jurisdictional

The Government next claims that Plaintiffs’ claims must be dismissed for lack

of subject matter jurisdiction under Rule 12(b)(1) because “prudential

principles” preclude standing. (Def. Br. at 21.) This argument is misplaced.

The “general prohibition on a litigant’s raising another person’s legal

rights” is a judicially self-imposed limit[].” Allen v. Wright, 468 U.S. 737,

751 (1984). As such, it is “flexible and not jurisdictional in nature.”

American Iron & Steel Institute v. Occupational Safety and Health

Administration, 182 F.3d 1261, 1274 (11th Cir. 1999) (emphasis added). As a

matter of law, the Government’s prudential standing argument provides no

grounds for dismissal for lack of subject matter jurisdiction.

2. Plaintiffs assert their own claims, not Hungary’s

The Government’s argument posits a moral inversion. The Government argues in

effect that Plaintiffs – the true owners of the Gold Train property, from whom

it was stolen by agents of the Hungarian Fascist Government – have no direct

interest in their own property, but have only an indirect interest derivative

of the direct interest of the successor Hungarian Government. Perhaps sensing

how outrageous its argument is, the Government disavows belief in its factual

basis, claiming only that it is based on “their [i.e., Plaintiffs’] theory.”

(Def. Br. at 21.)

Plaintiffs have never said that the Hungarian Government had a superior

interest to their property. This was stolen property. The Plaintiffs never

lost title to it, and neither the Hungarian Fascist Government nor the

successor Hungarian Government ever gained good title to the property. (FAC at

¶ 304.) And, neither did the Army.

Plaintiffs’ point is that the United States restituted looted property “to the

Governments of the rightful owners,” i.e., the country of origin. (Petropoulos

Supp. Aff. at ¶ 5.) This policy was followed not because the Governments of

the countries of origin had superior claims than the “rightful owners,” but

rather was based on administrative convenience. (Id. at ¶ 18.) Rather than

processing the claims of thousands of individuals, it was the policy of the

U.S. to, in effect, permit the countries of origin to act as the “agents” of

the rightful owners and deal only[65] with them. This administrative choice

does not confer a superior legal interest in the property.

3. Even if prudential standing principles apply, Plaintiffs satisfy the

requirements

While Plaintiffs deny that they are asserting Hungary’s rights, rather than

their own, it is nevertheless clear that, even if third-party prudential

standing analysis applies, Plaintiffs satisfy these requirements. The “general

prohibition against third-party standing” is intended to “ensure[] that the

courts hear only concrete disputes between interested litigants who will frame

the issues properly.” Harris v. Evans, 20 F.3d 1118, 1121 (11th Cir. 1994). In

contrast to the amorphous claims common in standing jurisprudence, Plaintiffs

present a concrete dispute: they seek compensation for personal property that

they allege was misappropriated by the Government. It is hard to imagine

litigants more interested than rightful property owners who, despite the

hardships they have endured, are vigorously pursuing their claims for

compensation in the twilight of their lives.

Plaintiffs in any event satisfy the three factors set forth in Powers v. Ohio,

499 U.S. 400 (1974), to allow third-party standing. The Government does not

even contest the first requirement, injury in fact. The second factor requires

a close relationship between the litigant and the third party; this test, too,

is met. As the Supreme Court has recognized, “the relationship between the

litigant and the third party may be such that the former is fully, or very

nearly, as effective a proponent of the right as the latter.” Singleton v.

Wulff, 428 U.S. 106, 115 (1976). Such is the case here. Many Plaintiffs are

citizens or former citizens of Hungary. It is Plaintiffs’ property that is at

issue, not Hungary’s; Plaintiffs are the real parties in interest. Hungary is

obligated by the 1947 Treaty of Peace to restore property seized from Jews or,

if restoration is impossible, to compensate them. (Article 27.) Thus,

Hungary’s only conceivable interest in the property is to ensure that its use

is to compensate the owners. Hungary’s interests are not only “properly

aligned” with the Plaintiffs’ (Harris, 20 F.3d at 1123), they are entirely

congruent. The Government relies on the spurious argument that the 1947 Treaty

of Peace and/or the 1973 Settlement Agreement set the Plaintiffs and Hungary

at odds. (Def. Br. at 23-24.) As we show below, neither of these documents

bars Plaintiffs’ right to recover. (See infra at § VIII.C.)

The third prudential standing factor is that there be “some hindrance” to the

third party’s asserting its own interest. Curiously, the Government says not a

word here about either the Treaty or the Settlement Agreement. Rather, it says

merely that Hungary is a “sovereign state” and there is “no reason that it

cannot protect any interest it thinks it may have regarding the Gold Train.”

(Def. Br. at 24.) The reason is obvious. The Government’s argument with

respect to the second factor demolishes its argument on the third factor.

Clearly, from the Government’s viewpoint, the Treaty and the Agreement are a

hindrance to Hungary bringing suit. Not a bar, but a hindrance. The Government

would clearly raise these issues if Hungary sued which would make the

litigation more protracted and uncertain. And, it must be recalled, the object

of such litigation would not be to compensate Hungary, but the rightful owners

of the property. Thus the cost-benefit calculus would present a “practical

barrier[]” to suit by Hungary sufficient to meet the hindrance factor. Cf.

Powers, 499 U.S. at 415 (small financial stake and burdens of litigation

present sufficient hindrance to support third party standing).

V. THE COURT HAS SUBJECT MATTER JURISDICTION OVER

PLAINTIFFS’ DAMAGE CLAIMS BECAUSE EACH

CLAIM IS MONEY MANDATING

As discussed above, the Court has subject matter jurisdiction over any claim

for damages founded upon the “Constitution, or any Act of Congress or any

regulation of an executive department, or upon any express or implied

contract” that is fairly interpreted as money mandating. Without question,

Plaintiffs’ claims are money mandating and founded upon these very sources.

A. Plaintiffs’ Contract, Takings, And Exaction Claims Are Money Mandating

Implied-in-fact contract claims are money mandating. Hatzlachh Supply Co. v.

United States, 444 U.S. 460, 466 (1980); Quality Tooling, Inc. v. United

States, 47 F.3d 1569, 1575 (Fed. Cir. 1995). The Tucker Act provides a waiver

of immunity for Plaintiffs’ contract claims to proceed, as the Court has

implicitly held. Rosner, 231 F. Supp. 2d at 1210 n.9.

Fifth Amendment Takings claims are money mandating.[66] Plaintiffs have

briefed this issue extensively already and hereby incorporate that briefing by

reference.[67] In short, the Just Compensation Clause of the Fifth Amendment

provides its own independent waiver of sovereign immunity and requires

compensation whenever property is taken for public use. Jacobs v. United

States, 290 U.S. 13, 16 (1933); Yearsley v. W. A. Ross Constr. Co., 309 U.S.

18, 22 (1940); Davis v. Passman, 442 U.S. 228, 242-43 n.20 (1979); First

English Evangelical Lutheran Church v. County of Los Angeles, 482 U.S. 304,

315 (1987); Alder v. United States, 785 F.2d 1004, 1009 (Fed. Cir. 1986); El-Shifa

Pharmaceutical Industries Co. v. United States, 55 Fed. Cl. 751 (2003)

(rejecting Ashkir, relied upon by the Court); Turney v. United States, 115 F.

Supp. 457 (Ct. Cl. 1953).

Illegal Exaction claims are money mandating. An illegal exaction claim is a

due process claim for money that has been improperly retained by the

Government (in violation of law). It is viable even where the money is not

paid directly to the Government. By definition, such a claim is money

mandating. Aerolineas Argentinas v. United States, 77 F.3d 1564, 1572-73 (Fed.

Cir. 1996) (en banc); Eastport S.S. Corp. v. United States, 178 Ct. Cl. 599,

605 (1967); Eversharp, Inc. v. United States, 125 F. Supp. 244, 247 (Ct. Cl.

1954); Pan Amer. World Airways Inc., v. United States, 122 F. Supp. 682,

683-84 (Ct. Cl. 1954); Bernaugh v. United States, 38 Fed. Cl. 538, 543 (1997),

aff’d, 168 F.3d 1319 (Fed. Cir. 1998) (taking of property); Bowman v. United

States, 35 Fed. Cl. 397, 401 (1996) (taking of property). The failure of a

plaintiff to establish that the exaction was contrary to law does not deprive

a court of jurisdiction, but is an adjudication on the merits. Aerolineas

Argentinas, 77 F.3d at 1574.

Plaintiffs’ illegal exaction claim is that the Government retained their

property in violation of the law based on the Constitution (due process and

takings), Decree No. 3, and other policies and laws in effect in occupied

Austria. As the Government explained in the Portrait of Wally case:

Under the military decrees and policies in effect in post-war Austria,

property, including artwork, seized by the United States Forces in Austria was

sorted and turned over to the country from which the object had been taken.

Portrait of Wally, at 109, Ex. 17 Walton Decl.; In re Portrait of Wally, at

*47 (all property taken under Decree No. 3 must be returned to country of

origin). Accordingly, because the Government violated the law and, in doing

so, received money in effect from the sale of Plaintiffs’ property to help pay

for programs that the Government was obliged to fund,[68] Plaintiffs state an

illegal exaction claim.

B. The Court Has Jurisdiction To Determine Which Of Plaintiffs’ International

Law Claims Are Money Mandating, And Adjudicate The Merits Of Those That

Are[69]

The Supreme Court has clarified that the Court has jurisdiction to decide the

merits of Plaintiffs’ so-called international law claims. Rasul v. Bush, 124

S. Ct. 2686, 2004 U.S. Lexis 4760 (2004). In Rasul, the Court of Appeals held

the federal courts “lack jurisdiction to consider challenges to the legality

of detention of foreign nationals captured abroad in connection with

hostilities and incarcerated at the Guantanamo Bay Naval Base, Cuba.” Id. at

2690. The Supreme Court reversed.

The Supreme Court’s most relevant discussion concerns the Al Odah detainees.

They alleged that the Government’s failure to inform them of the charges

against them, restrictions on the right to counsel, and their lack of access

to the courts violated the Constitution, international law, and treaties of

the United States. Id. at 2691. They asserted federal jurisdiction. Relying on

Johnson v. Eisentrager, 339 U.S. 763 (1950), the Court of Appeals had held,

among other things, that aliens outside the United States could not assert

these constitutional rights, and therefore dismissed the complaint for lack of

jurisdiction. Id. at 2691-92.

The Supreme Court explained that the decision in Eisentrager rested on “six

critical facts.” Id. at 2693. In Eisentrager, the individuals were (a) enemy

aliens; (b) who has been or resided in the United States; (c) and captured

outside the territory of the United States and held in military custody as a

prisoner of war; (d) where he or she was tried and convicted by a Military

Commission sitting outside the United States; (e) for offenses against laws of

war committed outside the United States; (f) and was at all times imprisoned

outside the United States. Id. Moreover, the Court emphasized that the

petitioners could assert all of their claims because the U.S. exercised

custody over them, even though that custody was outside the territorial

jurisdiction of the courts. Id. at 2695.

The Court distinguished at length the Guantanamo detainees from the Nazi war

criminals (known enemy aliens) at issue in Eisentrager, and in the end

concluded that nonresident aliens are entitled to the privilege of litigation

in federal courts.

The courts of the United States have traditionally been open to nonresident

aliens. Cf. Disconto Gesellschaft v. Umbreit, 208 U.S. 570, 578 (1908) (“Alien

citizens, by the policy and practice of the courts of this country, are

ordinarily permitted to resort to the courts for the redress or wrongs and the

protection of their rights”). And indeed, 28 U.S.C. §1350 explicitly confers

the privilege of suing for an actionable “tort . . . committed in violation of

the law of nations or a treaty of the United States” on aliens alone.

Id. at 2698-99. Rasul clearly holds that the Court has jurisdiction to decide

Plaintiffs’ claims.

Moreover, and perhaps more importantly, the Supreme Court recently confirmed

that Congress granted an implied private right of action to aliens when it

enacted 28 U.S.C. § 1350. Congress limited this cause of action to those

claims having definite content and an almost universal degree of international

acceptance among civilized nations. Sosa v. Alvarez-Machain, 124 S. Ct. 2739,

2004 U.S. Lexis 4763, at *71 (June 29, 2004).[70] The Court explained that

district courts can and should recognize these federal common law claims and

enforce such norms, just as the courts have been doing since the nation’s

founding. Citing to the watershed rulings of the modern era, including

Filartiga v. Pena-Irala, 630 F.2d 876, 890 (2d Cir. 1980), Judge Edwards’

concurrence in Tel-Oren v. Libyan Arab Republic, 726 F.2d 774, 781 (D.C. Cir.

1984), and In re Estate of Marco Human Rights Litig., 25 F.3d 1467, 1475 (9th

Cir. 1994), the Court explained that these rulings are “generally consistent”

with the Court’s decision in Sosa. Sosa, at *71.[71]

The Constitutional authority that a federal court possesses to create or find

a cause of action is derived from the court’s “general jurisdiction to decide

all cases ‘arising under the Constitution, laws, or treaties of the United

States.’” Correctional Services Corp. v. Malesko, 534 U.S. 61, 66 (2001).

Therefore, although the nomenclature is to describe these claims as

international law claims, that description is incorrect. Of legal necessity,

the claims are ones that “arise under” federal law either through the

“Constitution, laws, or treaties of the United States.”

Expropriation of private property without any compensation has attained the

special status to become federal law and actionable under 28 U.S.C. § 1350.

Restatement (Third) of Foreign Relations Law § 712; Banco Nacional de Cuba v.

Chase Manhattan, 658 F.2d 875, 891 (2d Cir. 1981) (“the failure to pay any

compensation to the victim of an expropriation constitutes a violation of

international law”); West v. Multibanco Comermex, S.A., 807 F.2d 820, 831-32

(9th Cir. 1987) (same); Kalamazoo Spice Extraction Co. v. The Provisional

Military Gov’t of Ethiopia, 729 F.2d 422, 426 (6th Cir. 1984) (same); Shanghai

Power Co. v. United States, 4 Cl. Ct. 237, 240 (1983); 1 L. Oppenheim,

International Law, § 155, at 352 (8th ed. Lauterpacht 1955) (which also

reflects a correct statement of law from earlier editions); see also H.R. Rep.

No. 1487, 94th Cong., 2d Sess. 19-20, reprinted in 1976 U.S.C.C.A.N. 6604,

6618 (taking violates international law if it is done “without payment of the

prompt adequate and effective compensation required by international law” or

is “arbitrary or discriminatory in nature”).

The Government has resolutely adhered to this principle, until now. See

generally 8 M. Whiteman, Digest of International Law 1085-1136 (1967). This

view, consistently adhered to by the Government until now, is commonly

referred to as the Hull Doctrine because the most celebrated expression of

this opinion came from United States Secretary of State Cordell Hull to the

Government of Mexico in 1938 on the subject of Mexico’s agrarian takings. Hull

explained: “under every rule of law and equity, no Government is entitled to

expropriate private property, for whatever purpose, without provision for

prompt, adequate, and effective payment therefor.” Note of Secretary of State

Hull, Aug. 22, 1938, 19 Dept. of State Press Releases No. 465, Aug. 27, 1938,

at 140;[72] Shanghai Power, 4 Cl. Ct. at 240. Moreover, this fact, among

others, helped convince the court in Shanghai Power that it was obliged to

apply international law consistent with U.S. policy to the facts of the case.

There is no doubt that rights created by virtue of an expropriation are backed

by accepted principles of international law. Moreover, recognition of such

rights is not contrary to our public policy, but, indeed, is consistent with

the repeated expressions of our State. . . .

Our Government has, however, been among the strongest proponents of the view

that the right to full and fair compensation exists and must be respected by

other nations. It would be inappropriate for this court to adopt a contrary

position.

Shanghai Power, 4 Cl. Ct. at 241. This claim is money mandating.

Notably, the Government recently confirmed this view of the law in the most

emphatic of terms, stating to the court in the Portrait of Wally case:

The principles preventing seizure of property from private citizens during

wartime and governing restitution of such property, particularly after World

War II, have been unambiguously subscribed to by scores of nations, including

Austria and the United States. In the Hague Convention of 1907,[73] forty-one

nations, including Austria and the United States, agreed to the prohibition of

the seizure of property during wartime from private citizens. Hague Convention

of 1907, Article 56 (“All seizure of, destruction of, willful damage done to

institutions of this character, historic monuments, works of art and science,

is forbidden, and should be made subject to legal proceedings.”). During World

War II, these principles were reiterated by the Allies in the London

Declaration of 1943,[74] in which eighteen nations warned the Nazi regime that

all confiscations of property were subject to restitution. And Article 26 of

the Austrian State Treaty of 1955 confirmed the adoption of these principles

of restitution by Austria and the Allies.

Portrait of Wally, at 161-62, Ex. 17 Walton Decl.

Courts have recognized that disgorgement and/or restitution are proper forms

of civil relief for violations of international law, and that such claims are

privately actionable under 28 U.S.C. § 1350. Bolchos v. Darrel, 3 F.Cas. 810 (D.S.C.

1795); Respublica v. Delongchamps, 1 U.S. (1 Dall.) 111, 116 (Pa. Oyer &

Terminer 1784); see, e.g., The Venus, 12 U.S. (8 Cranch) 253, 297 (1814) (“The

law of nations is a law founded on the great and immutable principles of

equity and natural justice”).

Plaintiffs bring this claim against the United States under the waiver of

sovereign immunity provided in the Tucker Act. The claim is money mandating

and founded on an Act of Congress, specifically 28 U.S.C. § 1350. No

additional waiver is required.[75]

C. Provisional Handbook And The Army Field Manual Are Binding On The Conduct

Of The U.S. Army As Its Own Regulation And Create Substantive Rights That Are

Money Mandating

The Supreme Court has expressly held that military powers during war-related

foreign occupation are “regulated and limited . . . directly from the laws of

war . . . from the law of nations.” Dooley v. United States, 182 U.S. 222, 231

(1901); 11 Ops Att’y Gen. 297, 299-300 (1865) (laws of war and general laws of

nations “are of binding forced upon the departments and citizens of the

Government”). The codification of those laws is found in the Army Field Manual

27-10, The Rules of Land Warfare. See Morrison v. United States, 492 F.2d

1219, 1225 & n.8 (Ct. Cl. 1974) (explaining it a “compilation of legal

principles that relate to land warfare. It is based upon treaties ratified by

the United States, statutory law, and applicable custom,” and indicating

provisions tied to statutes and texts of treaties are binding law).

Certain statutes or regulations require compensation for violations, while

others are money mandating because they are “reasonably amenable” to an

interpretation, drawing all “fair inferences,” that violations demand

compensation. Fisher v. United States, 364 F.3d 1372, 1377 (Fed. Cir. 2004).

They include provisions of substantive law or regulations that Plaintiffs

allege the Government violated which require compensation when hostilities

cease and include, Decree No. 3 and Paragraphs 323, 326, 331, and 345 of the

Army Field Manual. Therefore, the Tucker Act provides a waiver of sovereign