Who Put Gen.

Idi

Amin

in Power?

The

following extract is from an article published by

The Monitor (Uganda)

on March 31, 2002

There has

long been suspicion that Britain

organised

the 1971 coup in Uganda

which brought Idi

Amin

to power. Recently released Foreign Office papers show that the Israelis were

more likely to have been the culprits.

But Britain and Israel rushed to help

Amin

and sold him weapons.

In early

January 1971 a plot is being

hatched

in Uganda that will unleash a terror that has become a byword for evil in

Africa. General Idi

Amin

is about to become the military dictator of Uganda, throwing out President

Milton Obote.

Amin

and Obote

have been at daggers drawn for months.

Obote

has demoted his chief of staff, and is now preparing to have him arrested,

possibly murdered.

As the crisis

mounts, the Foreign Office in London and its representative in Kampala are

engaged in another serious matter. One of

Obote's

ministers has said in a speech that during colonial rule the British had

punished Obote's

grandfather by hanging him up by the hair for several hours. The High

Commission in Kampala want to know if this could be true and ask the Foreign

office in London if there is any evidence. The chaps in the Foreign Office in

London, languid, patronising,

wonder if you can hang someone up by "woolly African hair". "I suppose it is

just possible that unorthodox punishment might have been meted out to him I

will bear the story in mind when I speak to my

Langi

historian friend at Oxford", writes the Uganda desk officer on Jan. 5.

In their

cynical world-weary way they exchange messages on the subject until January

25th when the Foreign Office finally sends a note saying it can find no

evidence for the allegation. Someone has scribbled in the margin that it all

seems a bit irrelevant now.

Obote was overthrown that

morning.

Obote

had gone to Singapore attending a summit of Commonwealth leaders. The Ugandan

president was no friend of the British. He bitterly

criticised

British arms sales to South Africa and he had

nationalised

British companies in Uganda worth millions of pounds. He was expected to give

Ted Edward Heath, the British Prime Minister, a hard time at the Commonwealth

meeting.

There has

long been a suggestion that the British government engineered the coup. If

true, the plotters certainly did not tell the Foreign Office. Richard Slater,

the High Commissioner in Kampala, was caught completely unawares.

His early

telegrams suggest bewilderment. But he immediately goes to the embassy that he

believes to be close to Amin,

the

Israeli.

He is right.

Colonel Bar Lev,

the

Israeli

military attaché, has already met

Amin

on the day of the coup and has been out on the streets of Kampala. Officially

the First Secretary at the Embassy,

Bar Lev

has been in Uganda for five years and has recently been responsible for

setting up a paramilitary police force and training the army and police.

All the

British High Commission telegrams immediately after the coup quote

Colonel

Bar Lev.

He says that Amin

had all pro Obote

officers in the army arrested because

Obote

was going to have Amin

arrested on his return from Singapore.

Bar Lev

discounts any possibility of any moves against

Amin

by army units up country. "It appears that

Amin

is now firmly in control of all elements of army (sic) which controls vital

points."

London is

excited. "There is a good deal of interest here and we are receiving a number

of enquiries," writes Sir Alex Douglas-Home, the Foreign Secretary.

By the end of

the first day the Foreign Office is already considering

recognising

Amin's

rule. But in Tanzania, President Julius

Nyerere

is already accusing Britain of

organising the coup and the

British are afraid of being too close to

Amin

too soon. They decide not to lead the way in recognition but be close behind

others that do. After a few days they persuade Kenya to lead the way in

recognising

the new regime.

The

day after the coup, Slater says he has been to talk to Colonel Bar Lev who has

just been talking to Amin

again. "He made it clear at once that (Amin)

wanted me to be made aware of his intentions" says Slater.

Amin,

Bar Lev tells him, wants to hold elections and restore multi party democracy

to Uganda within three or five months. Bar Lev also lists the advice he is

giving to Amin.

In London the Foreign Office concludes: "We now have a thoroughly pro-Western

set up in Uganda of which we should take prompt advantage.

Amin

needs our help."

Britain let Israel or rather

Colonel Bar Lev take the lead and avoid being seen as too close to the

Israelis in Uganda while increasing contact in Tel Aviv. Bar Lev informs the

British that "all potential foci of resistance have been eliminated". A number

of pro-Obote

officers are shot but Bar Lev explains to the British that "Amin's

plan" had been "to let Obote

return and then shoot him at the airport, together with a number of those who

had gone to meet him. This plan was abandoned because of the difficulty of

synchronising

it with the liquidation of pro-Obote

elements in the army."

Bar Lev also says that the police

chief, Erinayo

Oryema,

was being chased by Amin's

troops and took refuge in Bar Lev's residence. The Israeli boasts that he

persuaded Oryema

to surrender and persuaded Amin

to forgive him and include him in the new regime. (Oryema

was later murdered by Amin

in 1977 together with fellow minister

Oboth

Ofumbi

and Anglican Archbishop Janan

Luwum).

In London the British want to know

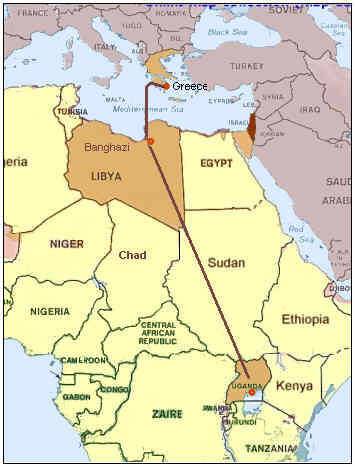

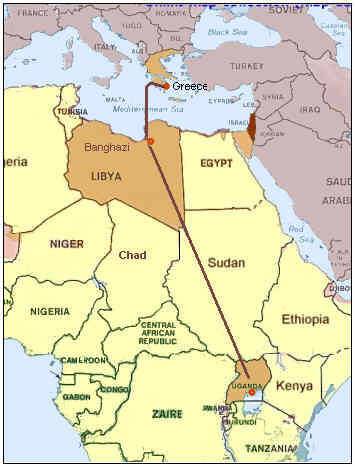

why Uganda is so important to Israel. The High Commissioner spells it out:

"The main Israeli objective

here is to ensure that the rebellion in southern Sudan keeps on simmering for

as long as conditions require the exploitation of any weakness in the Arab

world. They do not want the rebels to win. They want them to keep on

fighting."

Sudan supports the Palestinian

cause against Israel and Israel is determined to make Sudan pay by providing

arms and ammunition to the southern Sudanese rebellion. Uganda's co-operation

is vital. Israel also wants Uganda's vote at the United Nations.

Sir Alec

Douglas-Home, Britain's Foreign Secretary and chief advocate of arming

apartheid South Africa, is keen for Britain to back the new government. When

British intelligence reports that

Obote

has arrived in Khartoum on Jan. 29 and may try to re-enter Uganda from the

northern border, the foreign secretary orders that a warning message be sent

to Amin

through the Kenyans.

Soon after a

more sinister Briton turns up in Kampala. Bruce Mackenzie is a British

intelligence officer resident in Kenya who was also a roving ambassador for

President Jomo

Kenyatta.

It was also certainly Mackenzie who persuaded Kenya to

recognise

Amin,

though Kenya's other neighbours;

Somalia and Tanzania treat the coup as mutiny.

Mackenzie is

a cantankerous former fighter pilot with a handlebar moustache and firm views

about who is on "our side" and who is an enemy. He immediately urges London to

back Amin,

telling the Foreign Office to sell him

armoured

cars.

Two days

later an internal Foreign Office assessment reads: "General

Amin

has certainly removed from the African scene one of our most implacable

enemies in matters affecting Southern Africa Our prospects in Uganda have no

doubt been considerably enhanced providing we take the opportunities open to

us "

Amin

is certainly making all the right noises for the British. He has said he will

tell other African leaders not to

criticise

Rhodesia or South Africa, he will not

nationalise

British firms in Uganda and sees Britain as an ally that has done much for

Uganda.

To pursue

these "opportunities" an increasingly

sceptical

Slater is ordered "to get as close to

Amin

as you can and see whether you can develop a degree of familiarity which would

enable you to feed a certain amount of advice."

But what are

these opportunities? Britain sends out a Foreign Office minister, Lord Boyd,

who meets Amin

on April 3. Amin,

he reports, wants a signed portrait of Queen Elizabeth and a royal visit as

soon as possible. Amin

tells Lord Boyd that he has written her Majesty "a very nice letter".

The British

like this. Even more they like

Amin's desire for guns. He

wants to be able to hit Khartoum with bombers. The Israelis have already

obliged by providing ten refurbished American-made Sherman tanks and lots of

small arms. But Amin

wants armoured

cars and aircraft. He likes the new Harrier jump jet that Britain is

developing and, incredibly, the British think of selling them as well as

Phantoms and Jaguars, all of them heavyweight fighter bombers.

With a haste

that upsets the Ministry of

Defence, the Foreign Office

brings over some senior officers to observe a display of British weaponry in

action. From Kampala Slater's warnings to proceed cautiously are swept aside

by the likes of Sir Alec Douglas-Home.

He writes:

"The P(rime)

M(inister)

will be watching this and will, I am sure, want us to take quick advantage of

any opportunity of selling arms. Don't overdo the caution."

But it

transpires Amin

is playing a double game. Slater's caution is proved right.

Amin

told the British how much he admired them and their weapons. He has told the

Americans exactly the same thing. This worries Britain less than the

possibility that he will approach the French with a similar request.

On March 3,

Mackenzie urges Britain to supply them quickly. He says

Amin

is relying primarily on Israel, then on Britain and lastly on Kenya. He then

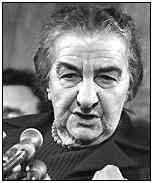

flies off to Israel to see Prime Minister, Golda

Meir

and General Moshe Dayan.

Seven years later Amin

had Mackenzie murdered, placing a bomb on his plane as he left Uganda after a

brief visit, ironically to try to sell

Amin

weapons.

In Kampala

Slater seems to give up. He even begins to warm to

Amin,

noting his popularity and his clownishness. "He has the wherewithal to provide

a satisfactory administration and has shown great qualities of leadership and

a marked flair for PR..." though he admits he is "Large, ungainly,

inarticulate and prone to gout He has earned a great deal of popularity by

mixing freely driving his own jeep, ignoring security precautions. I believe

him sincere in his wish to hold elections." Slater concludes that there is no

alternative. "I had reached the end of the road with

Obote",

he writes.

Yet his

caution about Amin

had been right. Amin's

love affair with Britain and Israel lasted just over a year.

Israel overplayed its hand in helping

to put Amin

in power and thought he was their puppet. He resented that, especially when

they demanded payment for the help they were giving Uganda.

Israel gives Amin a jet

|

Secondly in February 1972 peace was established in Sudan. An important

reason for the Israelis to be in Uganda was removed. In the end neither

Israel nor Britain would give Amin the weapons he wanted, though the

Israelis did give him an executive jet.

|

Idi Amin's

plane

Carl

Taylor was a corporate pilot. His career covered 30-something years and the

world.He had several "adventures", maybe none to compare with this one. Betty

remembers hearing that he piloted planes for people like John F. Kennedy in

Wisconsin during his presidential campaign, for Actress Elizabeth Taylor when

she was married to Senator John Warner. And, also for the Pro-basketball team,

Lakers, way back before they moved to California. The family had a scare when

he piloted with the Lakers...They heard one day in early 60's, that their

plane had crash-landed in a cornfield in Iowa. Knowing he was their pilot at

the time, they were really scared!! But, turns out, he was sick and stayed in

New York City that day and his co-pilot had taken the flight. No serious

injuries in the crash landing and Carl got to go and fly the plane out of the

cornfield!! He commented that it was harder to fly the plane out than the

landing might have been!! Sadly, Carl's career and life ended in April 1981,

just 5 years after the Idi Amin incident, when the plane with he and two

businessmen crashed on landing approach near the Alpena, Michigan airport. He

is buried in the Ft. Snelling National Cemetery in Minneapolis, MN.

Carl Taylor was the pilot who flew Idi

Amin's president's Westwind jet back to it's Israeli builders. Carl was at the

Uganda airport when Idi Amin came to the airport on a bicycle to meet them.

This was just 2 months after the 4th of July Israeli raid on Entebbe to free

more than 100 hostages from an Air France jet that was hijacked.

http://www.rcpbml.org.uk/wdie-02/d02-62.htm#idi

By Richard Dowden

17 August 2003

When Radio

Uganda

announced at dawn on 25 January 1971 that Idi Amin was

Uganda's

new ruler, many people suspected that Britain had a hand in the

coup.

However, Foreign Office

papers released last year point to a different conspirator: Israel.

The first

telegrams to London from the British High Commissioner in Kampala, Richard

Slater, show a man shocked and bewildered by the

coup.

But he quickly turned to the man who he thought might know what was going on;

Colonel Bar-Lev, the

Israeli defence attaché.

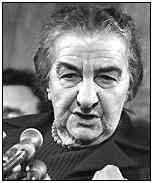

Golda Meir

He found the Israeli colonel with

Amin. They had spent the morning of the coup together. Slater's next telegram

says that according to Colonel Bar-Lev: "In the course of last night General

Amin caused to be arrested all officers in the armed forces sympathetic to Obote

... Amin is now firmly in control of all elements of [the] army which controls

vital points in Uganda ... the Israeli defence attaché discounts any possibility

of moves against Amin."

|

The

Israelis moved quickly to consolidate the coup. In the following days

Bar-Lev was in constant contact with Amin and giving him advice. Slater

told London that Bar-Lev had explained "in considerable detail [how] ...

all potential foci of resistance, both up country and in Kampala, had been

eliminated". Shortly afterwards Amin made his first foreign trip; a state

visit to Israel. Golda Meir, the Prime Minister, was reportedly "shocked

at his shopping list" for arms.

But

why was Israel so interested in a landlocked country in Central Africa?

The reason is spelt out by Slater in a later telegram. Israel was backing

rebellion in southern Sudan to punish Sudan for supporting the Arab cause

in the Six-Day War. "They do not want the rebels to win. They want to keep

them fighting."

|

The Israelis

had helped train the new

Uganda

army in the 1960s. Shortly after independence Amin was sent to Israel on a

training course. When he became chief of staff of the new army Amin also ran a

sideline operation for the Israelis, supplying arms and ammunition to the rebels

in southern Sudan. Amin had his own motive for helping them: many of his own

people, the Kakwa, live in southern Sudan.

Obote,

however, wanted peace in southern Sudan. That worried the Israelis and they were

even more worried when, in November 1970

Obote

sacked Amin. Their stick for beating Sudan was suddenly taken away.

The British may

have had little to do with the

coup

but they welcomed it enthusiastically. "General

Amin has certainly removed from the African scene one of our most implacable

enemies in matters affecting Southern Africa...," wrote an enthusiastic Foreign

Office official in London.

The man who

argued most vehemently for Britain to back Amin with arms was Bruce McKenzie, a

former RAF pilot turned MI6 agent. (Amin murdered him seven years later.)

He flew to Israel shortly after the

coup

and, as if getting permission to back Amin,

he reported to Douglas-Home: "The way is

now

clear for our High Commission in Kampala to get close to Amin."

But the

cautious Mr Slater in Kampala remained reluctant. Urged on by McKenzie,

Douglas-Home gave Slater his orders: "The PM will be watching this and will, I

am sure, want us to take quick advantage of any opportunity of selling arms.

Don't overdo the caution."

Shortly

afterwards Amin was invited for a state visit to London and dinner at Buckingham

Palace.

|

This is an excellent documentary

film that captures the man in his true colours, exactly as he would like

to have been seen. A

favourite line from the film is when

Amin

describes how

Golda

Meir

of Israel would provide “very good entertainments” for him when he visited

Israel. There are

innumerable moments that ought to have the viewer splits; the bits when he

is chatting to the animals, the bit when he explains how he is at one with

the people and how much they love him, the bit when he explains his own

brand of democracy.

|

The the first tele grams to London from the British överkommissarien in

Kampala, Richard Slater, shows a man as been shocked and been confused of kuppen.

But he turned himself fast to the man he

believed knew what as was taking place; Colonel

Bara

lives, the Israeli Defence

Attaché. He striked

on the Israeli Colonel with the muffler. The had paid the morning then

kuppen

was implemented together ". “the Israelis acted quickly in order to reinforce

kuppen. The the following

days each Bara lives in constant contact with the muffler and gave him councils.

Slater told for London that Bara lives had explained 'in detailed details [how]…

all potential concentrations of obstruction, both in the country and in Kampala,

had been eliminated”. “shortly then the done muffler their first utlandsresa; a

government visit in Israeli. Golda Meir, premiärministern, each according to

information received “shocked over his purchase list” of weapons”.

Coup in Uganda (Idi

Amin)

Idi

Amin,

a UK and Israeli backed general, replaces the elected government of

Uganda

in a military coup.

The Israeli attaché,

Colonel Rar-Lev,

spends the day of the coup advising the new dictator.

Eric le Tocq,

of the UK Foreign Office, writes

"Our prospects in Uganda have no boubt

been considerably enhanced".

Amin

had been running British concentration camps in

Kenya

during the independence movement in the 1950s, where he earned the title of "The

Strangler".

He begins one

of Africa's most brutal reigns of terror killing his friends, the clergy,

soldiers, and ordinary citizens. His first state visits are to UK and

Israel,

who sell him arms. The West continues to finance his regime until 1979.

Old telegrams unearthed by

The Independent

revealed that Israel helped Amin to take power in the 1971 coup.

Find out the

reasons behind it.

Thanks

YW

Loke

for the pointer. Also read

earlier blog

for context.

Posted by jeffooi at August 19, 2003 06:41 AM |

TrackBack

A traditionally

anti-Israel

newspaper unearthed telegrams supposedly made by another historically anti-Israel

diplomat to

Ida

Amin

whom before even his

coup

already supported Palestinians and incited violence against the Jews? And all

this while any news about

Ida

Amin

in

Israel is

negative? If this is true and got out on

Israel's

press at that time, it would be the end of the current civilian government.

And as the only

ally in Africa,

Israel

help Uganda with its army, not specifically

Amin.

Ida

Amin

rose to power in the military in the first place because of

Obote,

the person he stole power from when he was in Singapore.

Amin

had a rich military history, first serving in the King's African Rifles.

And

infighting in Sudan would have continued regardless of Ugandan support. The

rebels were of Christian and Animist minority, fighting against the Islamist

government who was enslaving them. If they were fighting because of Ugandan

support, well, it wouldn't have gone on for years to come. Fighting in fact

stop because of American and Egyptian pressure. If

Israel

wanted fighting to go on, they are better off directly aiding the rebels, like

they did with Bangladeshi rebels in the Pakistani civil war.

And who welcomed Amin into their

territory as a state visitor? Britain or Israel? The Independent didn't also

show proof of the telegrams, and forgets to note Israel is the closest Western

country to Uganda, and most from Europe at that time transit via that way.

And mind you, Europe was far more supportive of

Israel

then than now, especially between the six day war and the Yom Kippur War.

| |

|

Meister

Eckehart |

Publicerad: 18-08-2003

|

| |

| Idi Amin, Israel och

massmedia |

| |

Budskapet att Ugandas forne

despot Idi Amin avlidit har under dagen återberättats

i världens massmedier. Amins nekrologer har snarast tagit formen av

nidskrifter där det påpekas hur han under sin regeringsperiod 1971

till 1979 låtit döda 300.000 människor och expatrierat landets 50.000

man starka indiska befolkning. Vad dock i princip inga medier berättar

är att Idi Amin fördes till makten av Israel. När det påpekas vilket

oerhört inflytande judar har över massmedia i hela västvärlden brukar

apologeterna kontra med att många medier skulle vara negativt

inställda till Israel, som om det förändrar sakläget. Något som

däremot är ytterst relevant i sammanhanget är hur oerhört mycket mer

negativt inställda samma medier i regel är mot vita nationer, samt hur

för Israel prekära sanningar tystas ned. Fallet Amin är et tydligt

sådant exempel. Av alla de massmedier vi undersökt är det endast

brittiska The Independet som i artikeln 'Reveald: how Israel helped

Amin to take power', berör hur Israel förde Amin till makten. Budskapet att Ugandas forne

despot Idi Amin avlidit har under dagen återberättats

i världens massmedier. Amins nekrologer har snarast tagit formen av

nidskrifter där det påpekas hur han under sin regeringsperiod 1971

till 1979 låtit döda 300.000 människor och expatrierat landets 50.000

man starka indiska befolkning. Vad dock i princip inga medier berättar

är att Idi Amin fördes till makten av Israel. När det påpekas vilket

oerhört inflytande judar har över massmedia i hela västvärlden brukar

apologeterna kontra med att många medier skulle vara negativt

inställda till Israel, som om det förändrar sakläget. Något som

däremot är ytterst relevant i sammanhanget är hur oerhört mycket mer

negativt inställda samma medier i regel är mot vita nationer, samt hur

för Israel prekära sanningar tystas ned. Fallet Amin är et tydligt

sådant exempel. Av alla de massmedier vi undersökt är det endast

brittiska The Independet som i artikeln 'Reveald: how Israel helped

Amin to take power', berör hur Israel förde Amin till makten.

Precis som The Independets journalist, Richard Dowden,

konstaterar: "När Radio Uganda vid gryning den 25:e januari lät

meddela att Idi Amin var landets nya ledare misstänkte många att

Storbritannien hade ett finger med i kuppen. Dokument som släpptes av

utrikesdepartementet förra året pekar dock ut en annan konspiratör:

Israel".

"De första telegrammen till London från den brittiska

överkommissarien i Kampala, Richard Slater, visar en

man som chockats och förbryllats av kuppen. Men han vände sig snabbt

till den man han trodde visste vad som pågick; överste Bar-Lev,

den israeliske försvarsattachén. Han träffade på den israeliske

översten med Amin. De hade spenderat morgonen då kuppen genomfördes

tillsammans". "Israelerna agerade snabbt för att befästa kuppen. De

följande dagarna var Bar-Lev i konstant kontakt med Amin och gav honom

råd. Slater berättade för London att Bar-Lev hade förklarat 'i

ingående detaljer [hur] ... alla potentiella koncentrationer av

motstånd, både i landet och i Kampala, hade eliminerats". "Kort

därefter gjorde Amin sin första utlandsresa; ett statsbesök i Israel.

Golda Meir, premiärministern, var enligt uppgift 'chockad

över hans inköpslista' av vapen".

Det förhindrade dock inte Israel att förse Amin med vapen, och

därutöver tränade israeliska militärer de Amintrogna soldaterna.

Israel hade sedan Ugandas självständighet 1962 tränat landets armé.

Idi Amin själv levde ett tag i Israel där han blev specialutbildad,

och parallellt med hans senare roll som överbefälhavare för den

ugandiska armén blev han avlönad av Israel för att förse kakwa-folket

i södra Sudan med vapen i kampen mot den arabiska regimen i norr, ett

krig som rasar än idag. Motivet tros vara att Sudan allierat sig med

de flesta övriga arabstaterna mot Israel vilket under denna tid

kulminerade i Sexdagarskriget.

En ytterst intressant detalj som Dowden avslöjar i sin artikel är

att Bruce McKenzie, en MI6-agent, "den man som

häftigast argumenterade för att Storbritannien skulle stötta Amin", "flög

till Israel kort efter kuppen, som om han fick godkännande att stötta

Amin rapporterade han till Douglas-Home: 'Det är nu fritt fram för vår

överkommissarie i Kampala att närma sig Amin'".

Varför behöver en brittisk MI6-agent be Israel om lov för hur den

brittiska utrikespolitiken skall föras gentemot en afrikansk

kuppledare?

Israel skickade ner flera överstar som utgjorde Amins rådgivare,

och ordnade kontrakt för israeliska företag. Ett av dessa företag

byggde den internationella Entebbe-flygplatsen, något som kom att vara

av avgörande betydelse då Mossad 1976 stormade ett Air France-plan på

väg till Israel med 102 judar ombord, men kapades av palestinier och

landade på Entebbe.

Kort efter sitt makttillträde började Idi Amin rensa ut det

utländska inflytandet i landet. Den indiska minoritet som dominerade

landets ekonomin fördrevs, varav en stor del flyttade till

Storbritannien. Amin försökte ersätta dessa med personer från hans

egen stam, kakwa-folket, och höll andra folk, däribland

tutsiminoriteten i söder, på avstånd från makten. Denna politiska

etnocentrism kom snart även att gå ut över de som fört honom till

makten: israelerna. Efter denna snopna kovändning anklagades Idi Amin

omgående för antisemitism och den massmediala kritiken mot den

inledningsvis hyllade kuppledaren intensifierades.

Israel har nu återtagit sitt inflytande över Uganda. Idag är tutsin

Yoweri Museveni en av flyktingarna som lämnat

Rwanda 1959 under de etniska striderna med hutuerna i landet

president. Musevenis närmaste militäre rådgivare är juden

David Agmon, en israelisk överste av första graden. Agmons

ställning i Israel var tidigare minst sagt framträdande då det var han

som vid Benjamin Netanyahus tillträde som

premiärminister blev utsedd till dennes högste stabschef. När sedan

Kongo-Kinshasas (då fortfarande kallat Zaire) president Mobuto

Seso-Seko störtades 1997 avgick Agmon plötsligt och fick på

något sätt rätten till alla guldfyndigheter i östra Kongo. Bolaget via

vilket Agmon utvinner guldet har det missvisande namnet Australian

Russell Resources, då bolaget förutom att vara registrerat i

Australien har föga med landet att göra. I rådande krigstider är

Agmons roll som presidentens närmaste militärrådgivare minst sagt

inflytelserik, och tillsammans med en grupp andra israeler syns han

allt oftare tillsammans med Museveni i en rad olika sammanhang.

Då Uganda under kriget i Kongo byggde ut sitt flygvapen köptes

MiG-21-plan in från Polen. Den som arrangerade affären var juden

Amos Golan, och istället för att skicka

stridsflygplanen direkt till Uganda fördes de till Israel där de

restaurerades för motsvarande 200 miljoner kronor. Det var även i

Israel de ugandiska stridspiloterna, 13 till antalet, fick sin

16-månadersutbildning för sammanlagt 130 miljoner kronor. Golan kom

senare ä ven att sälja 62 stridsvagnar av modell T-55 till Uganda, men

hans oerhörda fräckhet manifesterades då det visade sig att endast

åtta av dessa fungerade.

En ytterligare dimension i den israeliska inblandningen i området

hamnade i dagens ljus den 26:e september 1998 då ett flygplan

kraschade i Uganda nära den kongolesiska gränsen. Ombord på flygplanet

fanns en av president Musevenis brorsöner, överste Jet Mwebaze,

och den israeliske juden Zeev Shif, som i bagaget

hade med sig över en miljon dollar. Det förmodas att de var på väg att

hämta upp en guldlast från östkongolesiskt territorium, då ockuperat

av ugandiska styrkor. Shif var även med om att under märkliga former

ta över Ugandas Kommersiella Bank, tillsammans med den ugandiske

generalmajoren Salim Saleh; Saleh var en av Amos

Golans närmste män i samband med vapeninköpen via Israel.

I april 1999 flögs drygt 120 israeliska militärer till Uganda för

att utbilda presidentens skyddsstyrka i krigföring med artilleri och

stridsvagnar. Parallellt lades även en stororder på gevär av märket

Stirling från det israeliska företaget Silver Shadow.

Mot bakgrund av vilka som förde Idi Amin till makten och försåg

hans soldater med vapen och träning är det intressant att se hur dessa

fakta fullständigt ignoreras i "svensk" massmedia. I Göteborgs-Posten

nämns hur israeler fördrevs ur Uganda, men ingenting om deras tidigare

förehavanden i landet. I Aftonbladet berättar Staffan

Heimersson om hur han vid två tillfällen träffat Amin, som

beskrivs av Heimersson som "ett skräckinjagande monster", men

"också som en älskvärd clown, som kunde göra narr av den vite

mannen, de forna kolonialherrarna". Jag är ytterst tveksam till

att Heimersson eller Aftonbladet skulle få för sig att kalla en person

som gör narr av negrer för "älskvärd". Å andra sidan bedömer såväl

Heimersson som Aftonbladet folk olika baserat på rastillhörighet,

vilket här framgår väl.

Heimersson berättar vidare om Amins kannibalism och hans benägenhet

att mata krokodiler med meningsmotståndare. Apropå fördrivandet av

landets indier försäger Heimersson sig dock, säkerligen omedveten

därom. Han menar att fördrivandet "var inte bara omoraliskt mot en

lojal folkgrupp som haft rötter i Uganda i nära hundra år. Det var

dessutom oklokt; det var indierna som med flit och affärs- och

hantverkskunnande höll landet rullande. Han tog Uganda tillbaka mot

stenåldern".

Hur kommer det sig att just indierna och inte den negroida

befolkningen dominerade landets ekonomi? Och, hur kommer det sig att

ingen negroid grupp idag kunnat övertaga indiernas forna roll? Svaret

återfinns givetvis i rasliga skillnader i intelligens, etnocentrism

och förmågan att vänta på långsiktiga mål. Heimersson giver sig som

väntat inte in i några spekulationer kring detta, och har med största

sannolikhet aldrig kontemplerat däröver. De forna brittiska

kolonialherrarna främjade inte indisk entreprenörsanda fram negroid,

om någon nu tror sig finna svaret där. En av marxisternas älsklingar,

indiern Mahatma Gandhi, klagade under sin tid som

journalist i den brittiska kolonin Sydafrika över hur förnedrande han

fann det att landets indier behandlades som negrer och exempelvis

behövde fördas i samma tågvagnar som dem. Idi Amin förde heller inte

Uganda till stenåldern, utan mot det stadium området befunnit sig i

före kolonialismen, helt i linje med den civilisatoriska regression

som påträffas snart överallt i det subsahariska Afrika.

I Expressen kväder Ulf Nilson inte orden över Amin,

eller "svinet Idi Amin" som han kallar honom. Självklart

ålägger Nilson en mängd andra länder skulden för vad Amin gjorde, och

lika självklart är Israel inte ett av dessa länder, trots att de förde

honom till makten och försåg honom med vapen. Nej, istället undrar han

"vad gjorde Sverige" och varför inte "Sverige begärde

honom utlämnad?" Behöver dessa frågor ens besvaras? Nilson har

ett svar, nämligen att "vi svenskar, i all vår skenhelighet",

"skiter i Afrika". Frågan är på vilket vis det skulle vara

skenheligt att inte lägga sig i andra länders agerande istället för

att berusade av hybris och självapoteos diktera över andra länder. Kan

det vidare inte anses ytterst skenheligt att likt Nilson försöka

ålägga Sverige skuld för vad en Israelsponsrad negroid despot gör i

Afrika? Enligt Nilson uppstod hållningen att inte ingripa andra

länders interna angelägenheter i samband med den westfaliska freden

1648. "Freden i Westfalen tillkom, bör vi minnas, efter trettio år

av svenska plundringståg, framförallt i Tyskland", hävdar Nilson.

Verkligen? Sverige deltog inte ens som aktiv part i trettioåriga

kriget förrän år 1630, och det var sannerligen inte "svenska

plundringståg" som i huvudsak utgjorde kriget eller födde freden. I

och med Nilsons uppenbara hat gentemot det svenska folket förvånar

dock att inte sådana banala saker som fakta förbises. Journalister

överhuvudtaget tenderar inte ha tid att bekymra sig över sådana

bagateller.

"Sanningen är att Afrika blivit planeten TELLUS svarta hål, en

fruktansvärd kontinent fylld av lidande och död, sjukdomar, fattigdom

och hopplöshet", inser Nilson, samt att "för hela kontinenten

gäller att man har det sämre ja, SÄMRE än man hade det under

kolonialismen". Orsaken kan väl inte ligga i en rasbiologisk

verklighet? Nej, det hela är troligen Sveriges fel; åtminstone är det

en rimlig förklaring utifrån Nilsons logik.

Fallet Idi Amin giver exempel på ett flertal viktiga aspekter av

den verklighet vi lever i: Israels globala makt; den "Israelkritiska"

massmedians tystnad om dessa fakta; tendensen i massmedia att bedöma

personer olika beroende på rastillhörighet, där vita utgör en paria

och rent av skuldläggs för andra rasers förehavanden. Inget av detta

bör förvåna, ty det är ett så ständigt återkommande mönster. Det

understryker emellertid allvaret i läget och vikten av reaktion i form

av aktion. Det räcker inte med att inse hur vi översköljs med lögner

och hat, utan vi måste inse varför och agera utefter våra insikter. De

som angriper oss bryr sig inte mer om våra liv än de liv Idi Amin

skördade, och det är våra liv de är ute efter.

|

|

|

Israel

Revealed:

how

Israel

helped

Amin

to take power

|

Typical really, it would make sense that

one of the most fascist regimes the world has ever seen

supported one of the most despotic leaders in Africa.

Israel seems

to think it has a God-given right to interfere anywhere it likes

because they're Jewish so that means they're more important than

the rest of us. Like I said, typical...

|

When Radio Uganda

announced at dawn on 25 January 1971 that Idi Amin was

Uganda's new ruler, many people suspected that Britain had

a hand in the coup. However, Foreign Office papers

released last year point to a different conspirator:

Israel.

|

The first telegrams to London from the British High Commissioner

in Kampala, Richard Slater, show a man shocked and bewildered by

the coup.

But he quickly turned to the man who he thought might know what

was going on;

Colonel Bar-Lev, the

Israeli defence attaché. He found the Israeli colonel with Amin.

They had spent the morning of the coup together. Slater's next

telegram says that according to Colonel Bar-Lev: "In the course

of last night General Amin caused to be arrested all officers in

the armed forces sympathetic to Obote

...

Amin

is now firmly in control of all elements of [the] army which

controls vital points in Uganda ... the Israeli defence attaché

discounts any possibility of moves against

Amin."

The Israelis moved quickly to consolidate the coup. In

the following days Bar-Lev was in constant contact with Amin and

giving him advice. Slater told

London that Bar-Lev had explained "in considerable detail [how]

... all potential foci of resistance, both up country and in

Kampala, had been eliminated". Shortly afterwards Amin made his

first foreign trip; a state visit to Israel. Golda Meir, the

Prime Minister, was reportedly "shocked at his shopping list"

for arms.

But why was Israel

so interested in a landlocked country in Central Africa? The

reason is spelt out by Slater in a later telegram.

Israel

was backing rebellion in southern Sudan to punish Sudan for

supporting the Arab cause in the Six-Day War. "They do not want

the rebels to win. They want to keep them fighting."

The Israelis had helped train the new Uganda army in the 1960s.

Shortly after independence

Amin was sent to

Israel

on a training course. When he became chief of staff of the new

army Amin

also ran a sideline operation for the Israelis, supplying arms

and ammunition to the rebels in southern Sudan.

Amin

had his own motive for helping them: many of his own people, the

Kakwa, live in southern Sudan. Obote, however, wanted peace in

southern Sudan. That worried the Israelis and they were even

more worried when, in November 1970 Obote sacked

Amin.

Their stick for beating Sudan was suddenly taken away.

The British may have had little to do with the

coup

but they welcomed it enthusiastically. "General

Amin

has certainly removed from the African scene one of our most

implacable enemies in matters affecting Southern Africa...,"

wrote an enthusiastic Foreign Office official in London.

The man who argued most

vehemently for Britain to back

Amin

with arms was Bruce McKenzie, a former RAF pilot turned MI6

agent. (Amin

murdered him seven years later.) He flew to

Israel

shortly after the coup and, as if getting permission to back

Amin,

he reported to Douglas-Home: "The way is now clear for our High

Commission in Kampala to get close to

Amin."

But the cautious Mr Slater in Kampala remained reluctant. Urged

on by McKenzie, Douglas-Home gave Slater his orders: "The PM

will be watching this and will, I am sure, want us to

take

quick advantage of any opportunity of selling arms. Don't overdo

the caution."

Shortly afterwards

Amin

was invited for a state visit to London and dinner at Buckingham

Palace.

Full story...

|

|

|

|

Idi Amin: London stooge against Sudan

by Linda de Hoyos

Executive Intelligence Review,

June 9, 1995, pp. 52-53

In February 1971, Gen. Idi Amin came to power in

Uganda, in a military coup against President Milton Obote. British sponsorship

of the semi-literate Amin, son of a sorceress, was quickly evident; Britain was

one of the first countries in the world to recognize the Amin government, long

before any African country. And when relations with Britain had soured after

Amin expelled the Asian business community from Uganda, British intelligence

operative Robert Astles remained as Amin's mentor in Uganda until the very end.

Amin's tyranny, lasting until 1979, trampled Uganda's political and economic

institutions, leaving the country a wreckage from which it has never recovered.

For London, as the book {Ghosts of Kampala} by George

Ivan Smith reports, the primary reason for fostering the Amin power grab was

Sudan. Idi Amin was willing, in fact eager, to permit Uganda to be used as a

base of operations to aid the southern Sudanese in their war against Khartoum;

Obote was not.

Nurtured Nilotics

Amin, now safely ensconced in Saudi Arabia, was a

member of the Kakwa tribe, which straddles the borders of Uganda, Zaire, and

southern Sudan. The tribe supplied Amin with his power base in the Ugandan Army.

As a young man in 1946, Amin joined the King's African

Rifles, founded in 1902. The British had traditionally taken soldiers of this

outfit from the grouping designated ``Nilotic peoples,'' particularly southern

Sudanese. In London's recipe for colonial rule, minority groups were assigned to

the enforcement roles, enhancing reliability. In 1891, contingents of southern

Sudanese were recruited by Captain (later Lord) Lugard for service in Uganda on

behalf of the Imperial British East Africa Company. After Britain ruled Uganda

officially, large numbers of Dinka and Azande troops, then living in Egypt, were

sent to Uganda. Although nominally Muslim, they had fought against the Mahdi's

army in the 1880s, on the British side. In Uganda, they were called ``Nubis.''

After

Amin

took power, he staffed all Army command posts with ``Nubis,''

in much the same way that Yoweri Museveni's National Resistance Army is

commanded by Himas, or Tutsis of southern Uganda, and the Banyarwanda, former

Rwandan Tutsis. During the Sudanese civil war of 1955 to 1972, southern Sudanese

had been brought directly into the Ugandan Army, making Uganda the perfect

buttress for the southern Sudanese fighting Khartoum.

Obote bucks policy

In the early years of independence, Obote had invited

delegations from Israel to help

carry out farming projects in northern Uganda and to assist training the Army.

Israel had a specific interest in Uganda: its proximity to Sudan. The Israelis

were soon moving into southern Sudan to assist directly the Anyanya movement

against Khartoum. In 1966, however, Obote visited

Khartoum, and came to an agreement that Uganda would exert every effort to

restore peace in the south. But the policy was ignored by the Defense Ministry

and by Idi Amin, who was up to his eyeballs in smuggling operations in the Congo

(now Zaire) and Sudan. Amin was

in charge of an operation which smuggled gold and ivory out of Congo,

in exchange for giving weapons to Congolese rebels, and was brought before a

commission of inquiry when it was discovered that he was pocketing thousands of

dollars in the process. The commission further discovered that Amin had become

involved in the Congo venture through Robert Astles, who was making contacts

between the Congolese rebels and the Ugandan Army. Astles's private airline

company was handling the smuggling.

Amin put in to destabilize the Sudan, who was Egypt's

ally

|

|

Ugandan Army officers also charged that

Amin was working--against

government orders--with the Sudan rebels inside Sudan.

They alleged he went on a number of unauthorized flights with a foreign

pilot--possibly Astles--to

meet Sudanese rebels and arranged to supply them with materiel intended

for the Ugandan Armed Forces. A German

mercenary named Rolf Steiner was an accomplice in the operation. In his

autobiography, {The Last Adventurer,} Steiner relates that he had arranged

a meeting in Kampala ``under the supervision of General Idi Amin with the

purpose of reaching an agreement on the leadership of the [Sudanese]

liberation front.'' Out of this meeting, Steiner was given money to buy

goods wholesale and ship them across Uganda to the tribal chiefs in

southern Sudan. Steiner notes that ``although not all-powerful, he [Amin]

was strong enough to order his army to turn a blind eye to my harmless

smuggling service.''

|

Meanwhile, Obote refused to grant Israel landing rights

for their supplies to the Anyanya. The crisis over Sudan policy hit in November

1970. Steiner was arrested by Ugandan police upon reentering Uganda from Sudan.

Obote stated, in a later interview, ``The government of Uganda as such was not

involved in aiding the Anyanya but was involved in finding political solutions

in the Sudanese conflict. The arrest of Steiner brought out the fact that Israel

was using Uganda to supply Anyanya.'' Obote was couped while he was in Nairobi,

on his way back from the Singapore Commonwealth conference. As he relates,

``It is doubtful that Amin,

without the urging of the Israelis, would have staged a successful coup in

1971.... Israel wanted a client regime in Uganda which they could manipulate in

order to prevent Sudan from sending her troops to Egypt.... The coup succeeded

beyond their wildest expectations.... The Israelis set up in Uganda a regime

which pivoted in every respect to Amin, who in turn was under the strictest

control of the Israelis in Kampala.... The Israelis and Anyanya were hilarious;

the regime was under their control.''

When the

Sudanese civil war was halted in 1972,

Israel quickly lost interest in Amin. Enter Libya. In February 1972, Amin

visited Libya, striking a pact with its President Muammar Qaddafi. In March

1972, all Israeli personnel were told to leave Uganda. In August 1972, all

Asians were expelled, whereupon Britain withdrew its support for Amin. In

September 1972, Libya proffered full military assistance to Uganda and sent 500

technicians to Kampala. By 1974, the intelligence services in Uganda were being

run by Libya, and Libya was giving Amin Soviet MiG fighters. Libya even supplied

troops to defend Amin when the Tanzanian Armed Forces invaded Uganda to drive

Amin out. Overseeing the entire venture, from beginning to end in 1979, was

London's Astles.

The Israelis

were soon moving into southern Sudan to assist directly the Anyanya movement

against Khartoum. In 1966, however, Obote visited Khartoum, and came to an

agreement that

Uganda

would exert every effort to restore peace in the south. But the policy was

ignored by the Defense Ministry and by

Idi

Amin,

who was up to his eyeballs in smuggling operations in the Congo (now Zaire) and

Sudan. Amin

was in charge of an operation which smuggled

gold

and ivory out of Congo, in exchange for giving weapons to Congolese rebels,

and was brought before a commission of inquiry when it was discovered that he

was pocketing thousands of dollars in the process. The commission further

discovered that

Amin

had become involved in the Congo venture through

Robert Astles,

who was making contacts between the Congolese rebels and the Ugandan Army.

Astles's private airline company was handling the smuggling.

Congo and

Uganda:

a rush of

gold

In November the UN Security Council

adopted sanctions, which include freezing assets and travel restrictions,

against anyone breaking the arms embargo on the Democratic Republic of Congo.

The east of the country is rife with

smuggling,

especially in

gold.

Regional conflict that left 3 million dead between 1998 and 2003 has exhausted

the country, and general elections that were due this year have been pushed back

to June 2006.

By Stefano

Liberti

MONGBWALU,

a desolate village in Ituri district in the northeastern region of the

Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), looks like something out of an old

western. A single dusty road runs through it, with cafes on either side that

resemble saloons, a squalid hotel with a broken-down sign, and groups of

youths observing passersby as though they were expecting a shoot-out any

minute. The comparison with the Wild West isn’t fanciful, for here, as in the

towns that mushroomed in the United States during the

gold

rush, everything revolves around

gold.

Ituri

is right in the middle of one of the most important gold deposits on earth

(1). Several hundred kilograms are extracted every month from the primitive

mines around Mongbwalu. The gold is taken illegally to neighbouring Uganda,

from where it is exported to Europe, usually Switzerland. Because of the

enormous profits generated, the gold is much coveted - and the cause of the

bloody conflict that has plagued the DRC and this region since 1998 (2).

The subsoil of this huge African

country - formerly Zaire - is so gorged with minerals that it’s sometimes

called a geological outrage. From 1982, when the dictator Mobutu Sese Seko (in

power from 1965 to 1997) liberalised

gold

mining in parts of the country, Mongbwalu became a sort of tropical

Klondike. Thousands of small-scale miners threw

themselves into a business that continued through the worst moments of the

war. The miners still leave the village every day at dawn in battered old 4x4s

and follow the earthen tracks to the mines. There they split into teams and

start digging. The open pit mine resembles an enormous hive in which thousands

of people busy themselves inside mud combs. Some men stand waist deep in

water, digging feverishly and putting the earth in plastic crates that are

passed along by men pressed against the sides of the embankment.

Each team works for itself. The soaked

earth and stones are placed on a sieve above a pool of water. The first stage

is to look for

gold

dust. Then the more promising stones are broken with clubs in the hope of

finding veins of

gold.

“You have to know where to dig,” says Etienne, who spent 10 months in the

hills of Mongbwalu. Around him a group of young men are examining stone chips

in a sieve, hoping to find a few specks of

gold.

“No luck today,” says Etienne, “but I’m sure it’ll get better later. If we

find a good chunk, we’ll manage to get $5 each.”

At the top of the embankment you can

make out the ruins of a building. It is all that is left of the “factory”, the

public enterprise set up for

gold

extraction in the Kilo-Moto region to which Mongbwalu is the gateway.

Gold

mining was in full swing during Mobutu’s time, when Ituri was under the

control of the Kinshasa government. In those days the profits went straight

into Mobutu’s pockets, enabling him to amass a fortune in foreign banks. The

battle to gain control of this rich piece of land was triggered immediately

after his fall in 1997.

Africa’s largest

gold

seam

Kilo-Moto

is one of the most unstable areas in the Great Lakes region. Because of its

extraordinary potential - it has the largest gold seam on the continent - it

has been coveted by the main players of what has been called “the first

African world war” (which pitted government forces supported by Angola,

Namibia and Zimbabwe against rebels backed by Uganda and Rwanda).

In 1998, when the country was invaded

by Rwanda and

Uganda,

the region was occupied by the Kampala forces, which flew the

gold

straight back to

Uganda.

After the 2003 Sun City agreement in South Africa, foreign troops were obliged

to leave the country. The area then became the scene of

fighting between the Union of

Patriotic Congolese (UPC), supported by Rwanda, and the Front for National

Integration (FNI), backed by Uganda.

Sixty thousand people are thought to have died in these conflicts, despite

timid intervention by Monuc, the UN observer mission in the DRC, set up in

1999. After falling to the UPC, the region was taken back by the FNI.

The militiamen stand accused, among

other things, of subjecting workers to forced labour. According to a report by

Human Rights Watch (HRW), the FNI takes a percentage of the mined

gold

and extracts one dollar a day from the workers in exchange for allowing them

to work the mines (3). The soldiers hotly deny this. “It’s peace, our men are

unarmed. All the men here work for themselves and for the good of the

country,” says Iribi Pitchou Kasamba.

This small, stocky man became head of

the front after its leader, Floribert Ndjabu, was arrested in Kinshasa for

killing nine Bangladeshi Monuc troops in Ituri in February. Flanked by his

“lieutenants”, Kasamba inspires fear and respect in equal measure in the zone

around the mine. He describes the accusations by HRW as “total rubbish”,

adding that “the only money we’ve received is the $8,000 that AngloGold

Ashanti paid us quite voluntarily.”

This major South African company

obtained a 10,000sq km mining concession around Mongbwalu and has recently

been accused of bribing the rebel forces. Since 2003 the UN embargo prohibits

any support to armed rebels in the DRC (4). The company claims that it was

obliged to pay to guarantee the safety of its employees. But the scandal has

tarnished its image - particularly since it boasts an ethical policy inspired

by a commitment to “corporate social responsibility” (5). In any case

AngloGold Ashanti has not yet started to mine

gold

in its concession.

Shovels and sieves

Mining continues the primitive way,

with shovels and sieves. Near the site a crowd of men equipped with scales

gets ready to start buying. The luckier

gold-washers

crowd around them clutching handfuls of their precious find. This is the start

of the transaction. The

gold

dust in placed on a coal heater and mixed with nitric acid to separate any

impurities. The remaining

gold

is then weighed and sold. The price is about $10 a gram. The rate depends on

the market and increases the further you get from the mining area. In Bunia,

Ituri’s main town,

gold

fetches $11.5 a gram. The small-time buyers at the source, as well as the

dozens of others who gather in Mongbwalu’s main street, are the middlemen for

traders in Bunia and Butembo in the neighbouring province of North Kivu.

Numerous small jobs are grafted on to

the business of the mine itself. Women sell fruit, potatoes and rice; young

motorcyclists ferry people to and from the mining sites and the centre of

Mongbwalu.

There is also a motley crew of musicians who seem more comfortable with guns

than guitars and seem to monitor the comings and goings. The mere presence of

Kasamba is enough to deter anybody from speaking.

Only later, and anonymously, does

someone from Mongbwalu agree to give us his view: “In the factory and the

other mines near the village, the FNI’s control is limited. Since the Monuc

forces arrived the militia have had to be more discreet. But you only have to

go a few kilometres further out to see them back in their old ways, forcing

people to work for them, harassing them and confiscating

gold.”

The 140 Pakistani soldiers from Monuc

(6) who arrived in April, and who are in charge of disarming the militia, are

even more discreet than the rebels. They are confined to their camp outside

the village and their actions are limited to a few patrols. One of the leaders

of the contingent admitted that he didn’t really know what went on in the

mines.

At the Bunia headquarters, this state

of affairs is confirmed. “In theory Monuc could supervise the

gold

traffic,” says Karin Volkner, the mission’s political affairs officer, “but in

reality we don’t have the means to carry out that kind of control. There’s

only one military contingent in Mongbwalu. We’re thinking of sending a group

of civilians but so far we’ve only carried out exploratory missions.” The

Monuc forces are occasionally called in for heavy operations and to support

the elections that should end to the transition period (7), but they scarcely

bother with the

gold

smuggling

that goes on under their very noses.

In broad daylight

In Bunia

gold

dust is sold in broad daylight. In this village, ravaged by war and poverty

where thousands of refugees are crowded into a camp by the airport, the

gold

trade is the only commercial activity possible. Almost everyone seems to be at

it, in one or other of the two markets.

According to the new DRC mining code

established in 2002, government authorisation is required for wholesale

gold

purchasing (8) but nobody bothers about that in a region where the state is

totally absent. “Ituri suffers from government failure,” says Volkner. “The

Kinshasa government is very far away and has never bothered much about the

people to the east. On top of that, some ministers are directly involved in

raw materials trafficking and have no interest in establishing peace in the

region.”

The entire trade rests on a well-organised

network of small-scale miners, buyers and intermediaries. The town’s traders

sell the

gold

to a handful of middlemen, who smuggle it to Kampala. They use a variety of

vehicles (trucks, jeeps, motorbikes), or canoes to cross Lake Albert, making

the most of a total absence of controls at the Congolese border. As the

process advances, the number of people involved is reduced. In Kampala only

three companies buy the

gold;

all are managed by Indian entrepreneurs. The largest company,

Uganda

Commercial Impex Ltd (UCI) (9), has its headquarters in the suburb of

Kamutckia.

According to Jamnadas Vasanji Lodhia,

the owner of UCI: “We buy approximately 350kg of

gold

for a total of $5m. Our suppliers are always the same six or seven people, all

Congolese from Bunia and Butembo.” The best known of these is Kambala Kisoni,

owner of the Congocom Trading House. Kisoni also owns a small Antonov plane

that flies between Mongbwalu and Butembo almost daily under the name of

Butembo Airlines. According to UN experts, Kisoni has breached the arms

embargo many times and has transported arms and FNI personnel to Mongbwalu

(10).

When we reached Kisoni by telephone,

he denied the accusations. “They consider us accomplices or rebels but, in

fact, we’re hostage to the FNI people, who behave as though they run the area.

They charge us $60 every time we land at Mongbwalu. We’d like the Congolese

army to regain control of the region and establish some order.”

Kisoni did not deny exporting

gold

without authorisation from the mining ministry in Kinshasa. “It’s become

dangerous to export with a licence,” he explained. “Given the level of

corruption in the government, we’d risk losing everything. We used to have a

licence but our

gold

cargo was stolen three times. And we know that the thieves were connected to

the government.” Kisoni added that Congocom is simply an unofficial bank. “Gold

is the currency here. With our clients’

gold

we buy merchandise, which they sell in Congo. The Kampala buyers like UCI open

lines of credit for the big companies that supply our clients with the

products. We restrict ourselves to working as middlemen between the Ugandan

companies and the traders in eastern Congo.”

The

gold bought by UCI is melted down in the company’s Kampala headquarters.

The small ingots are then sent every month to Metalor Technologies SA in

Switzerland, a leading European dealer in precious metals. But since June the

market has apparently ground to a halt. Following the publication of the HRW

report, the Swiss company decided to stop

gold

imports. The UCI boss, Lodhia, was furious. “This trade has carried on for a

century,” he said. “I don’t understand why they are making such a fuss. They

accuse us of stealing wealth from Congo, but our suppliers are Congolese. With

the money they earn from us they buy goods to sell in their country where

there is nothing. They don’t buy arms, but sugar, coffee, blankets and

clothes. What’s the point of buying arms anyway? Congo is full of them. That’s

what earns the least money.”

Offshore bank accounts

Lodhia said he knew nothing about the

supposed links between his suppliers and the armed rebels in Ituri. He

confirmed visiting Bunia and Butembo, but denied ever having been to Mongbwalu.

“I’ve occasionally been to see clients in the east of the country,” he admits,

“but I’ve never visited the mines.” He showed us the company accounts that

record transactions with Congolese clients worth millions of dollars. Most of

the money is stored in offshore bank accounts in places like Mauritius or Hong

Kong. “Our clients don’t trust local banks,” he explained, “so we pay the

money into the accounts they choose. Which is totally legal.”

Indeed, the trade is legal. The

Ugandan government does not require certificates of origin. It merely levies a

0.5% duty on

gold

exports and an annual licence fee of $1,200. In theory imported metals should

be declared at the border, but it is so easy to cross the Congo-Uganda

border that nobody bothers with customs declarations.

The numbers reveal the extent of this

vast trade. In 2003 local

gold

production was worth $23,000. Officially imported

gold

totalled $2,000 while exported

gold

reached $45bn. The same data, supplied by the ministry for energy and

development in Kampala, reveals that

Uganda’s

gold

production totalled 40kg for that year, yet exports were more than four tonnes.

In 2002 official

production stood at 2.6kg with exports of 7.6 tonnes (11).

As a

result of this vast legalised smuggling operation, gold is the second biggest

Ugandan export after coffee.

“That’s no secret,” said Lodhia. “Everybody knows that the

gold

in Kampala comes from Congo. In any case the government is virtually

non-existent in former Zaire, especially in the east, and there are no

controls. It’s been like that since the Mobutu era.”

Uganda

has been the hub for Congolese gold since 1994,

when the Kampala government decided to withdraw the central bank’s monopoly in

buying precious metals, to scrap high export duties (of between 3% and 5%),

and to make the regulations on trading companies more flexible. Previously,

gold

from Ituri transited through Kenya where the trade had already been

liberalised. Lodhia admits to having switched from Nairobi to Kampala. “From a

logistical point of view, it’s much easier to work out of

Uganda,”

explained the Indian entrepreneur. “The country is nearer to the DRC and

security is excellent.”

The value of the

gold

increases as it travels from the Congolese towns to the Ugandan capital. UCI

buys at $13.5 per gram. The selling price abroad depends on fluctuations on

the international markets. “But we work on the basis of a profit margin of

0.5%,” explained Lodhia. “Gold

mining is a living for thousands of people in eastern Congo. Those Human

Rights Watch militants are lobbying intensively to stop it, but their

ideological thinking will end up hurting the very people they think they’re

defending. I’m losing money myself, but I’m not going to starve. If the Swiss

stop buying and I don’t find other outlets, then sooner or later I’ll have to

stop buying.”

There are thousands of people involved

in gold

smuggling,

from the miners in Mongbwalu to the big traders in Kampala and the middlemen

in Bunia and Butembo. Although there is no doubt that

gold

mining has supported - and continues to support - the rebels in the east of

the country, it would be difficult to prevent this through embargoes or other

means. UN experts believe that, given the size of the country, a total export

ban on natural resources would be an extremely costly measure and hard to

enforce (12). For them

the ideal solution would be to set up a “traceability” process that would

prevent smuggling to Uganda. But a system like the Kimberley process for

diamonds (13) has not yet been devised for precious metals.

According to Enrico Carisch, a UN

finance expert: “The only way to stop the warlords from making money would be

to put pressure on the region’s governments to end this regime of impunity.

The Ugandans, in

particular, should normalise bilateral trade with Congo.

But to do that, the Kinshasa government must regain control over the east of

the country with the help of the international community.” In a region where

the state is notable for its absence and

gold

is the only source of revenue for the majority of people, it is hard to

imagine how the

gold

mining business could be changed at one stroke - particularly with the strong

international demand for

gold.

Budskapet att Ugandas forne

despot Idi Amin avlidit har under dagen återberättats

i världens massmedier. Amins nekrologer har snarast tagit formen av

nidskrifter där det påpekas hur han under sin regeringsperiod 1971

till 1979 låtit döda 300.000 människor och expatrierat landets 50.000

man starka indiska befolkning. Vad dock i princip inga medier berättar

är att Idi Amin fördes till makten av Israel. När det påpekas vilket

oerhört inflytande judar har över massmedia i hela västvärlden brukar

apologeterna kontra med att många medier skulle vara negativt

inställda till Israel, som om det förändrar sakläget. Något som

däremot är ytterst relevant i sammanhanget är hur oerhört mycket mer

negativt inställda samma medier i regel är mot vita nationer, samt hur

för Israel prekära sanningar tystas ned. Fallet Amin är et tydligt

sådant exempel. Av alla de massmedier vi undersökt är det endast

brittiska The Independet som i artikeln 'Reveald: how Israel helped

Amin to take power', berör hur Israel förde Amin till makten.

Budskapet att Ugandas forne

despot Idi Amin avlidit har under dagen återberättats

i världens massmedier. Amins nekrologer har snarast tagit formen av

nidskrifter där det påpekas hur han under sin regeringsperiod 1971

till 1979 låtit döda 300.000 människor och expatrierat landets 50.000

man starka indiska befolkning. Vad dock i princip inga medier berättar

är att Idi Amin fördes till makten av Israel. När det påpekas vilket

oerhört inflytande judar har över massmedia i hela västvärlden brukar

apologeterna kontra med att många medier skulle vara negativt

inställda till Israel, som om det förändrar sakläget. Något som

däremot är ytterst relevant i sammanhanget är hur oerhört mycket mer

negativt inställda samma medier i regel är mot vita nationer, samt hur

för Israel prekära sanningar tystas ned. Fallet Amin är et tydligt

sådant exempel. Av alla de massmedier vi undersökt är det endast

brittiska The Independet som i artikeln 'Reveald: how Israel helped

Amin to take power', berör hur Israel förde Amin till makten.