5.1.3. Sensitivity of SAR Calculations to Permittivity Changes

5.1.4. Relative Absorption Cross Section

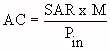

(Equation 5.25)

(Equation 5.25)

where Pin is the incident power density and M is the mass of the object exposed to EM fields.

Figure 5.7.

Calculated average SAR in a prolate

spheroidal model of an average man, as a function of

frequency for several values of permittivity. ![]() m is the

permittivity of muscle tissue.

m is the

permittivity of muscle tissue.

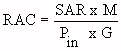

(Equation 5.26)

(Equation 5.26)

(Equation 5.27)

(Equation 5.27)

Figure 5.8.

Relative absorption cross section in prolate

spheroidal models of an average man, a rabbit, and a

medium-sized rat--as a function of frequency for E

polarization.

Figure 5.9.

Comparison of relative scattering cross

section (RSC) and relative absorption cross section (RAC) in

a prolate spheroidal model of a medium rat--for planewave

irradiation, E polarization.

5.1.5. Qualitative Dosimetry

E1p = E2p (Equation 5.28)

1E1n =

1E1n =  2E2n (Equation 5.29)

2E2n (Equation 5.29)

where Elp and E2p are components parallel to the

boundary, and Eln and E2n are component, perpendicular to the

boundary, as shown in Figure 5.10. It is important to

remember that Equations 5.28 and 5.29 are valid only at a

point on the boundary. From Equation 5.29, we can see that

E2n =  1 Eln /

1 Eln / 2; and if

2; and if  2 >>

2 >>  1, then E2n << E1n. Thus if Eln is the field in free space and E2n is the field in an absorber, the internal field at the boundary will be much weaker than the external field at the boundary when

1, then E2n << E1n. Thus if Eln is the field in free space and E2n is the field in an absorber, the internal field at the boundary will be much weaker than the external field at the boundary when  2 > >

2 > >  1 and the fields are normal to the boundary. Also, from Equation 5.28, we see that the external field and the internal field at the boundary are equal when the fields are parallel to the boundary. These two results will be used extensively in explaining relative energy absorption.

1 and the fields are normal to the boundary. Also, from Equation 5.28, we see that the external field and the internal field at the boundary are equal when the fields are parallel to the boundary. These two results will be used extensively in explaining relative energy absorption.

Figure 5.10.

Field components at a boundary between two media having different complex permittivities,  1 and

1 and  2.

2.

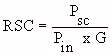

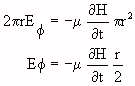

![]() (Equation 5.30)

(Equation 5.30)

For the very special case of a lossy dielectric cylinder

in a uniform H-field Equation 5.30 can be solved by deducing

from the symmetry of the cylinder and fields that E will have

only a ![]() component that will be constant around a circular

path, such as the one shown dotted in Figure 5.11. For E

constant along the circular path, and H uniform, Equation

5.30 reduces to

component that will be constant around a circular

path, such as the one shown dotted in Figure 5.11. For E

constant along the circular path, and H uniform, Equation

5.30 reduces to

(Equation 5.31)

(Equation 5.31)

Thus, Equation 5.30 shows that E is related to the rate of change of the magnetic flux intercepted by the object; and Equation 5.31 shows that for the very special case of Figure 5.11, the E-field circulates around the H-field and is directly proportional to the radius. For this example the circulating E-field (which produces a circulating current) would be larger for a larger cross section intercepted by the H-field. The generalized qualitative relation that follows from Equation 5.30 is that the circulating field is in some sense proportional to the cross-sectional area that intercepts the H-field. This result is very useful in qualitative explanations of relative energy absorption characteristics; however, this qualitative explanation cannot be used indiscriminantly.

Figure 5.11.

A lossy dielectric cylinder in a uniform magnetic field.

Ein = E e+ Eh (Equation 5.32)

where

QP1.

Ee is stronger when Einc is mostly parallel to the boundary of the object and weaker when Einc is mostly perpendicular to the boundary of the object.

QP2.

Eh is stronger when Hinc intercepts a larger cross section of the object and weaker when Hinc intercepts a smaller cross section of the object.

Figure 5.12.

Qualitative evaluation of the internal

fields based on qualitative principles QPl and QP2. Ee

is the internal E-field generated by Einc, the

incident E-field, and Eh is the internal

E-field generated by Hinc,the incident

H-field.

Table 5.1

Application of QP1 and QP2 To Planewave SARS

/d)2 , since the magnitude of the E- and H-fields is expected to

increase more rapidly than

/d)2 , since the magnitude of the E- and H-fields is expected to

increase more rapidly than  /d in the near-field region.

However, the reasons for the shape of the SAR curve may be

found from Figure 8.21, which shows the behavior of the

measured fields of the antenna (designated Einc and

Hinc with respect to an absorber). The direction of

the Hinc does not change with d, but the magnitude of

Hinc increases faster than

/d in the near-field region.

However, the reasons for the shape of the SAR curve may be

found from Figure 8.21, which shows the behavior of the

measured fields of the antenna (designated Einc and

Hinc with respect to an absorber). The direction of

the Hinc does not change with d, but the magnitude of

Hinc increases faster than  /d for d/

/d for d/ < 0.3. The

direction of Einc however, changes significantly with

d. In the far field, the angle

< 0.3. The

direction of Einc however, changes significantly with

d. In the far field, the angle  = 0.1, it is

about 70º. According to QP1, this change in angle has a

significant effect on Ee Thus the change in SAR with

d/

= 0.1, it is

about 70º. According to QP1, this change in angle has a

significant effect on Ee Thus the change in SAR with

d/ results from three factors:

results from three factors:

- Ee increases as the magnitude of Einc increases.

- Ee decreases as

increases.

increases.

- Eh increases as the magnitude of Hinc increases.

/d, Ee increases much more slowly than

/d, Ee increases much more slowly than  /d because of the

combination of factors 1 and 2. The average SAR, which is

proportional to E2in does not increase as fast as (

/d because of the

combination of factors 1 and 2. The average SAR, which is

proportional to E2in does not increase as fast as ( /d)2

because Ee affects Ein more than Eh

does. On the other hand, since the monkey-size spheroid is

relatively shorter and fatter than the man-size spheroid,

Eh has a stronger effect on Ein for the monkey

than for the man. Consequently, the SAR for the monkey

increases more rapidly as d decreases than does the SAR for

the man.

/d)2

because Ee affects Ein more than Eh

does. On the other hand, since the monkey-size spheroid is

relatively shorter and fatter than the man-size spheroid,

Eh has a stronger effect on Ein for the monkey

than for the man. Consequently, the SAR for the monkey

increases more rapidly as d decreases than does the SAR for

the man.

. The reasons for this

can be seen from Figures 6.37 - 6.39:

. The reasons for this

can be seen from Figures 6.37 - 6.39:

- Einc is slightly lower at 200 MHz and significantly lower at 300 MHz than at the other frequencies.

- Hinc is lower at 200 and 300 MHz than at the other frequencies.

- The angle

of Einc with the z axis is

significantly higher at 200 and 300 MHz than at the other

frequencies.

of Einc with the z axis is

significantly higher at 200 and 300 MHz than at the other

frequencies.

. According to QP1, as

. According to QP1, as  increases, the SAR

decreases. The effect of

increases, the SAR

decreases. The effect of  can be seen from the 300-MHz

curve which begins to rise rapidly at y/

can be seen from the 300-MHz

curve which begins to rise rapidly at y/ = 0.3, where

= 0.3, where  decreases steeply. A surprising aspect of the correspondence

between incident-field characteristics and the relative SAR

characteristics is that the correlation was based on the

values of the incident fields at only one point in space.

decreases steeply. A surprising aspect of the correspondence

between incident-field characteristics and the relative SAR

characteristics is that the correlation was based on the

values of the incident fields at only one point in space.

/y (as shown in Figure 6.37) for

0.15 < y/

/y (as shown in Figure 6.37) for

0.15 < y/ < 0.5 is slower than

< 0.5 is slower than  /y, the relative

SARs for an absorber at distance d from the dipole for both H

and K polarizations vary faster than (

/y, the relative

SARs for an absorber at distance d from the dipole for both H

and K polarizations vary faster than ( /d)2 in this region

(as seen in Figures 6.32 and 6.33). From the nature of the

incident fields (as shown in Figures 6.37-6.39), Eh

appears to dominate for K and H polarizations, while

Ee dominates for E polarization. The same behavior is

shown in a different way in Figure 5.13, where the calculated

average SAR for a prolate spheroidal model of an average man

is shown as a function of

/d)2 in this region

(as seen in Figures 6.32 and 6.33). From the nature of the

incident fields (as shown in Figures 6.37-6.39), Eh

appears to dominate for K and H polarizations, while

Ee dominates for E polarization. The same behavior is

shown in a different way in Figure 5.13, where the calculated

average SAR for a prolate spheroidal model of an average man

is shown as a function of  /d)2

variation, as shown in Figures 6.32 and 6.33.

/d)2

variation, as shown in Figures 6.32 and 6.33.

Figure 5.13.

Average SAR in a prolate spheroidal model of

an average man as a function of normalized impedance for each

of the three polarizations. (a = 0.875 m, b = 0.138 m, f =

27.12 MHz,  = 0.4 S/m, incident E-field is 1

V/m.)

= 0.4 S/m, incident E-field is 1

V/m.)

Figure 5.14.

Ratio of (SAR)e, to (SAR)h of a 0.07-m3

prolate spheroid for each polarization as a function of the

ratio of the major axis to the minor axis of the spheroid at

27.12 MHz,  = 0.4 S/m.

= 0.4 S/m.

Go to Chapter 5.2

Return to Table of Contents.

Last modified: June 14, 1997

© October 1986, USAF School of Aerospace Medicine, Aerospace Medical Division (AFSC), Brooks Air Force Base, TX 78235-5301

This is a Department of Defense computer system for authorized use only. DoD computer systems may be monitored for all lawful purposes, including to ensure that their use is authorized, for management of the system, to facilitate against unauthorized access, and to verify security procedures, survivability, and operational security. Using this system constitutes consent to monitoring. All information, including personal information, placed on or sent over this system may be obtained during monitoring. Unauthorized use could result in criminal prosecution.

POC: AFRL/HEDM, (210)536-6816, DSN 240-6816