- This chapter was revised by Eleanor R. Adair, Ph.D., Associate Fellow, John B. Pierce

Foundation Laboratory, Yale University. It includes material written by James L. Lords,

Ph.D., and David K. Ryser, Ph.D., from previous editions of this handbook and new material

added by Dr. Adair.

10.1. INTRODUCTION

- The study of thermoregulation--the responses that maintain a constant internal body

temperature--has flourished since Claude Bernard (1865) first demonstrated that the

temperature of the blood varies in different parts of the body. Bernard established that

food taken into the body is metabolized in the tissues and that the bloodstream

distributes the released energy throughout the body. The relative constancy of the

internal body temperature was part of his concept of the constancy of the milieu

intérieur, a necessity for optimal functioning and health of the organism. He pointed out

that the vasomotor nerves control the transfer of heat from deep in the body to the skin

and that this is a mechanism of the utmost importance to thermoregulation in homeotherms.

Bernard's discoveries underlie the modern science of thermophysiology and help us to

understand how man and animals can remain relatively independent of the thermal

environment, even when that environment contains potent or unusual thermal stressors.

- Thermal loads on the body can result from changes in metabolic heat production and from

changes in the characteristics of the environment (temperature, ambient vapor pressure,

air movement, insulation, and other environmental variables that may alter the skin's

temperature), Thermalizing energy deposited in body tissues by exposure to radiofrequency

electromagnetic radiation can be a unique exception to the normal energy flows in the

body, although metabolic activity in skeletal muscle can deposit large amounts of thermal

energy directly into deep tissues.

- All living organisms respond vigorously to changes in body temperature. Cold-blooded

animals, called ectotherms because they derive thermal energy mainly from outside the

body, regulate their body temperatures largely through behavioral selection of a preferred

microclimate. Warm-blooded animals, called endotherms because they can produce heat in

their bodies and dissipate it to the environment through physiological processes, often

rely largely on behavioral thermoregulation. Behavior is important to thermoregulation

because it is mobilized rapidly and aids the conservation of body energy and fluid stores.

When behavioral responses--which include the thermostatic control of the immediate

microenvironment--are difficult or impossible, the body temperature of endothermic species

is regulated by the autonomic mechanisms that control heat production, the distribution of

heat within the body, and the avenues and rate of heat loss from the body to the

environment.

- Other descriptive terms currently used include "temperature conformer" for

ectotherm and "temperature regulator" for endotherm. Some thermal physiologists

prefer a different classification, based on the quality of the thermoregulation: A

homeotherm normally regulates its body temperature within rather narrow limits by varying

its metabolic rate, heat and moisture loss, or position in the environment; a poikilotherm

may allow its body temperature to vary over a considerable range, and regulates that

variation by its position in the environment. Complications for the latter scheme arise

when one considers hibernators (endotherms that periodically become poikilothermic) or

ectotherms that are effectively homeothermic by virtue of efficient behavioral

thermoregulation. The terms "endotherm" and "ectotherm" are used in

the material that follows.

10.2. HEAT EXCHANGE BETWEEN ORGANISM AND

ENVIRONMENT

- Radiofrequency radiation may be regarded conveniently as part of the thermal environment

to which man and other endotherms may be exposed. Figure 10.1 is a schematic

representation of the sources of heat in the body and of the different routes by which

thermal energy may be transferred between the body and the environment. Heat is produced

in the body through metabolic processes (M) and may also be passively generated in body

tissues by absorption of RFR (

).

If the body temperature is to remain stable, this thermal energy must be continually

transferred to the environment. As outlined above, the balance between the production and

loss of thermal energy is so regulated by behavioral and autonomic responses that minimal

variation occurs in the body temperature of an endotherm.

).

If the body temperature is to remain stable, this thermal energy must be continually

transferred to the environment. As outlined above, the balance between the production and

loss of thermal energy is so regulated by behavioral and autonomic responses that minimal

variation occurs in the body temperature of an endotherm.

- Energy may be lost (Figure 10.1) by evaporation of water from the respiratory tract (

) or from the skin (

) or from the skin ( ), by dry-heat transfer from the skin

surface via radiation (

), by dry-heat transfer from the skin

surface via radiation ( ) or

convection (

) or

convection ( ), and by doing work

(W = force x distance) on the environment. Heat transfer by conduction is usually

insignificant in most species unless they are recumbent. When the environment is thermally

neutral, dry-heat loss predominates in the form of convective transfer to the air and

radiant transfer to the surrounding surfaces. A small amount of heat is always lost by the

diffusion of water through the skin (not shown in the figure).

), and by doing work

(W = force x distance) on the environment. Heat transfer by conduction is usually

insignificant in most species unless they are recumbent. When the environment is thermally

neutral, dry-heat loss predominates in the form of convective transfer to the air and

radiant transfer to the surrounding surfaces. A small amount of heat is always lost by the

diffusion of water through the skin (not shown in the figure).Figure

10.1.

A schematic diagram of the sources of body heat (including radiofrequency radiation) and

the important energy flows between man and the environment. The body is in thermal

equilibrium if the rate of heat loss equals the rate of heat gain. Figure modified from

Berglund (1983)

.

- When the temperature of the environment rises above thermoneutrality, or during vigorous

exercise or defervescence, the evaporation of sweat (

) dissipates large amounts of body heat. Evaporative water loss

through sweating occurs in man, the great apes, certain other primates, and a few other

species such as horses and camels. Many animals--such as dogs, cats, and rabbits--use

panting (increased respiratory frequency coupled with copious saliva production) to lose

heat by evaporation. Other species, such as the rodents, have no such physiological

mechanisms and must rely on behavioral responses which include seeking shade, burrows, or

aqueous environments and/or grooming their bodies with water, urine, or saliva to aid

evaporative cooling. Table 10.1 includes several thermoregulatory characteristics of

certain animals.

) dissipates large amounts of body heat. Evaporative water loss

through sweating occurs in man, the great apes, certain other primates, and a few other

species such as horses and camels. Many animals--such as dogs, cats, and rabbits--use

panting (increased respiratory frequency coupled with copious saliva production) to lose

heat by evaporation. Other species, such as the rodents, have no such physiological

mechanisms and must rely on behavioral responses which include seeking shade, burrows, or

aqueous environments and/or grooming their bodies with water, urine, or saliva to aid

evaporative cooling. Table 10.1 includes several thermoregulatory characteristics of

certain animals.

- The rate of heat loss from an endotherm is governed by the thermal characteristics of

the environment, as indicated in Figure 10.1; these include not only the air temperature (

) but also the air movement (v) and

humidity (RH). Two other environmental variables that affect heat transfer (not shown in

the figure) are the mean radiant temperature of surrounding surfaces , especially those

close to the body, and the amounts of insulation (fur, fat, feathers, clothing).

) but also the air movement (v) and

humidity (RH). Two other environmental variables that affect heat transfer (not shown in

the figure) are the mean radiant temperature of surrounding surfaces , especially those

close to the body, and the amounts of insulation (fur, fat, feathers, clothing).

- When the thermal energy produced in the body (including that derived from absorbed RFR)

is equal to that exchanged with the environment, the body is said to be in thermal

balance. Under these conditions the body temperature remains stable. When heat production

exceeds heat dissipation, thermal energy is stored in the body and the body temperature

rises (hyperthermia). On the other hand, when more heat is transferred to the environment

than can be produced or absorbed, the body temperature falls (hypothermia).

Table 10.1.

Thermoregulatory Characteristics Of Animals

10.3. THE THERMOREGULATORY PROFILE

- The particular thermoregulatory effector response mobilized at any given time, and its

vigor, will depend on the prevailing thermal environment. The ambient temperature is

frequently the only environmental variable specified in research reports, but the

specification of air movement and relative humidity is equally important. Figure 10.2, a

schematic thermoregulatory profile of a typical endotherm, illustrates how the principal

autonomic responses of heat production and heat loss depend on the ambient temperature.

The responses are considered to be steady state rather than transient, and the ambient air

is considered to have minimal movement and water content. Three distinct zones can be

defined in terms of the prevailing autonomic adjustment. Below the lower critical

temperature (LCT), thermoregulation is accomplished by changes in metabolic heat

production, other responses remaining at minimal strength . As the ambient temperature

falls further and further below the LCT, heat production increases proportionately. In a

cool environment RF energy absorbed by an endotherm will spare the metabolic system in

proportion to the field strength and will have no effect on other autonomic responses.

- At ambient temperatures above the LCT, metabolic heat production is at the low resting

level characteristic of the species, evaporative heat loss is minimal, and changes in

thermal conductance accomplish thermoregulation. Conductance is a measure of heat flow

from the body core to the skin and reflects the vasomotor tone of the peripheral

vasculature. As the constricted peripheral vessels begin to dilate, warm blood from the

body core is brought to the surface so that the heat may be lost to the environment by

radiation and convection. These vasomotor adjustments take place within a range of ambient

temperatures, called the thermoneutral zone (TNZ), that is peculiar to each species.

Insofar as they are known, the TNZs for animals commonly used in the laboratory are

indicated in Table 10.1. If an endotherm at thermoneutrality is exposed to RFR, augmented

vasodilation may occur so that the heat generated in deep tissues can be quickly brought

to the skin surface for dissipation to the environment.

- The upper limit of the TNZ is known as the upper critical temperature (UCT). At this

ambient temperature the endotherm is fully vasodilated and

Figure

10.2.

Thermoregulatory profile of a typical endothermic organism to illustrate the dependence of

principal types of autonomic responses on environmental temperature. LCT = lower critical

temperature; UCT = upper critical temperature; TNZ = thermoneutral zone.

dry-heat loss (by convection and radiation) is maximal. Further increases in ambient

temperature provoke the mobilization of heat loss by evaporation, either from the skin

(sweating) or the respiratory tract (panting). Man and certain other mammals have the

ability to sweat copiously to achieve thermoregulation in hot environments. It is

reasonable to assume that if these species were exposed to RFR at ambient temperatures

above the UCT, their sweating rate would increase in proportion to the field strength.

Other mammals, notably the rodents, neither sweat nor pant and when heat stressed must

depend on behavioral maneuvers to achieve some degree of thermoregulation; if the

opportunity for behavioral thermoregulation is curtailed, these animals can rapidly become

hyperthermic when heat stressed. The basic thermoregulatory profile of the selected

laboratory animal must therefore be considered in detail as part of the experimental

design of any research into the biological consequences of exposure to RFR; changes in any

measured thermoregulatory response will depend on the functional relationship between that

response and the prevailing ambient temperature. Other types of responses also may be

indirectly affected by the thermoregulatory profile if they interfere with efficient

thermoregulation (e.g., food and water consumption).

- Man exhibits profound adaptability in the face of environmental thermal stress,

particularly in warm environments. Figure 10.3 illustrates some of the fundamental data

collected by Hardy and DuBois (1941) for nude men and women exposed in a calorimeter to a

wide range of ambient temperature Because of the vigorous responses of heat production and

heat loss, the rectal temperature varies less than 1ºC across a 20ºC range of

calorimeter temperature. The TNZ is extremely narrow, occurring at about 28ºC in the

calorimeter and closer to 30ºC in the natural environment. Above the TNZ, evaporative

heat loss (whole-body sweating) is initiated that can attain rates of 2-3 L/h and up to

10-15 L/d (Wenger, 1983). Assuming normal hydration, it is difficult to increase metabolic

heat production (by exercise) to levels that cannot be dissipated by sweating, unless the

ambient temperature or vapor pressure is very high. Since human evaporative heat loss is

controlled by both peripheral and internal thermal signals (Nadel et al., 1971), only an

extraordinarily hostile thermal environment, which includes a source of RFR, can be

expected to seriously threaten man's thermoregulatory system.

Figure

10.3.

Thermoregulatory profile of nude humans equilibrated in a calorimeter to different ambient

temperatures. Data adapted from Hardy and DuBois (1941).

Way et al. (1981) and others (Stolwijk, 1983) have predicted minimal increases in brain

and body temperatures during local absorption of significant amounts of RF energy, because

of the rapid mobilization of evaporative heat loss and a significant increase in tissue

blood flow. Under the assumption that RF exposure provides a thermal stress comparable to

exercise (Nielsen and Nielsen, 1965) or an ambient temperature well above the TNZ, such

response changes would be predicted from knowledge of the human thermoregulatory profile

in Figure 10.3. On the other hand, significant temperature elevations in certain body

sites (e.g., the legs, arms, and neck) have been predicted by a two-dimensional

heat-transfer model of man exposed to a unilateral planewave at resonant and near-resonant

frequencies (Spiegel et al., 1980). These predictions should be verified in animal models

or, preferably, in human subjects exposed to comparable fields.

10.4. BODY HEAT BALANCE

- The most important principle involved in the study of autonomic thermoregulation of

endotherms is the first law of thermodynamics--the law of conservation of energy (Bligh

and Johnson, 1973). In the steady state the heat produced in the body is balanced by the

heat lost to the environment, so heat storage is minimal. This relationship can be

expressed by a heat-balance equation:

M ± W = R + C + E ± S (Equation

10.1)

in which

- M = rate at which thermal energy is produced through metabolic processes

- W = power, or rate at which work is produced by or on the body

- R = heat exchange with the environment via radiation

- C = heat exchange with the environment via convection

- E = rate of heat loss due to the evaporation of body water

- S = rate of heat storage in the body

- All terms in Equation 10.1 must be in the same units, e.g. , watts (the unit used

throughout this handbook). Physiologists commonly express these quantities in kilocalories

per hour, which can be converted to watts by multiplying by 1.163, the conversion factor.

As Equation 10.1 is written, negative values of R, C, and E may all cause a rise in the

body temperature; positive values may cause a fall. Work (W) is positive when accomplished

by the body (e.g., riding a bicycle), and this potential energy must be subtracted from

metabolic energy (M) to find the net heat (H) developed within the body. When W is

negative (e.g., walking downstairs), this heat is added to M. While W may be a significant

factor for humans or beasts of burden, it may be considered negligible for other

endotherms, particularly in a laboratory setting. Usually evaporative heat loss (E) is

positive; when E is negative, condensation occurs and thermal injury is possible.

- Because heat exchange by radiation, convection, or evaporation is always related in some

way to the surface area of the body, each term in Equation 10.1 is usually expressed in

terms of energy per unit surface area, e.g., watts per square meter. The most commonly

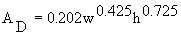

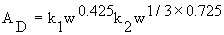

used measure of the body surface area of humans is that proposed by DuBois (1916),

(Equation 10.2)

(Equation 10.2)

where

= DuBois surface in square

meters

= DuBois surface in square

meters- w = body mass in kilograms

- h = height in meters

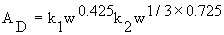

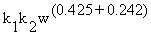

- As noted by Kleiber (1961), h for similar body shapes is proportional to a mean linear

dimension equal to

. Therefore,

to compare humans of different sizes, Equation 10.2 may be generalized as

. Therefore,

to compare humans of different sizes, Equation 10.2 may be generalized as =

= =

= (Equation 10.3)

(Equation 10.3)

- The ratio of surface area to body mass varies between species, so it is difficult to

establish a general rule for the determination of surface area. Many methods have been

devised for the direct measurement of the surface area of experimental animals, most of

which are inaccurate to some degree. In nearly all cases, the surface area is some

function of

.

.

- Although Equation 10.1 has no term for heat transfer through conduction (which is

usually insignificant under normal conditions), conduction combined with mass transfer

forms the significant mode of heat transfer called convection. Convective heat transfer in

air (C) is a linear function of body surface area (A), and the convective heat transfer

coefficient (

) is a function of

ambient air motion to the 0.6 power (

) is a function of

ambient air motion to the 0.6 power ( ) The amount of heat the body loses through convection depends on the

difference between the surface temperature of the skin (

) The amount of heat the body loses through convection depends on the

difference between the surface temperature of the skin ( ) and the air temperature, usually taken as the dry-bulb

temperature (

) and the air temperature, usually taken as the dry-bulb

temperature ( ). The value of the

heat-transfer coefficient depends on certain properties of the surrounding medium, such as

density and viscosity, as well as a shape/dimension factor for the body. Clothing

complicates the analysis and is often evaluated in terms of insulation (clo) units.

). The value of the

heat-transfer coefficient depends on certain properties of the surrounding medium, such as

density and viscosity, as well as a shape/dimension factor for the body. Clothing

complicates the analysis and is often evaluated in terms of insulation (clo) units.

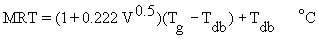

- Heat transfer by radiation is independent of ambient temperature. The wavelengths of the

radiation exchanged between two objects are related to their respective surface

temperatures; the net heat transfer by radiation is proportional to the difference between

their absolute temperatures to the fourth power and to the relative absorptive and

reflective properties of the two surfaces. In general, the net radiant-heat exchange

(where

= radiant-heat-transfer

coefficient) between a nude man and the environment involve a estimation of the mean

radiant temperature (MRT). MRT (alternate symbol

= radiant-heat-transfer

coefficient) between a nude man and the environment involve a estimation of the mean

radiant temperature (MRT). MRT (alternate symbol  ) can be derived from the temperature (

) can be derived from the temperature ( ) of a blackened hollow sphere of thin copper (usually

0.15-m diameter) having heat-transfer characteristics similar to those for the human body

(Woodcock et al., 1960):

) of a blackened hollow sphere of thin copper (usually

0.15-m diameter) having heat-transfer characteristics similar to those for the human body

(Woodcock et al., 1960): (Equation 10.4)

(Equation 10.4)

Clothing complicates this analysis as it does heat transfer by other modes. Heating by

RFR may further complicate the analysis of radiant-heat exchange between a man and his

environment, although Berglund (1983) has demonstrated that this complex situation can be

analyzed by conventional methods.

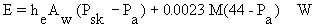

- The final avenue of heat loss available to man is that due to the evaporation of water.

The latent heat of vaporization of water at normal body temperature is 0.58 kcal/g; the

body loses this amount of heat when water is evaporated from its surfaces. Water from the

respiratory surfaces is continually being lost in the expired air. Water also continually

diffuses through the skin; this is called insensible water loss or insensible

perspiration. These two avenues contribute equally to a heat loss that totals about 25% of

the resting metabolic heat production of a man in a thermoneutral environment. However,

the major avenue of evaporative heat loss in man is sweating, which depends on the vapor

pressures of the air and the evaporating surface and is thus a direct function of both dry

bulb (

) and wet bulb (

) and wet bulb ( ) temperatures. When

) temperatures. When  , the air is at 100% relative humidity

and thus no water can be evaporated from the skin surface; at less than 100% relative

humidity, evaporation can occur. The interrelationships between these variables can be

determined from a standard psychrometric chart (ASHRAE Handbook, 1981). In Equation 10.1,

E represents the evaporative cooling allowed by the environment (

, the air is at 100% relative humidity

and thus no water can be evaporated from the skin surface; at less than 100% relative

humidity, evaporation can occur. The interrelationships between these variables can be

determined from a standard psychrometric chart (ASHRAE Handbook, 1981). In Equation 10.1,

E represents the evaporative cooling allowed by the environment ( ) and is in no way related to the level of evaporative

cooling required (

) and is in no way related to the level of evaporative

cooling required ( ) by the man.

) by the man.10.5. METABOLIC RATES OF MAN AND ANIMALS

- Because the metabolic heat production per unit body mass, or "Specific metabolic

rate," varies greatly with body size and proportion (somatotype), several measures of

this variable are in wide use. Figure 10.4 is a log-log plot of metabolic heat production

versus body mass for several animals and man. The solid line with a slope of 0.75 reveals

a strong correlation between body mass raised to the 0.75 power and metabolic heat

production. This empirical observation has prompted researchers to adopt power per unit

body mass, in units of watts per kilogram, as the standard metric for animal metabolic

rate.

Figure 10.4.

Logarithm of total metabolic heat production plotted against logarithm of body mass. (Data

taken from Tables 10.2 and 10.4.)

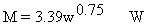

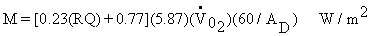

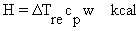

- The metabolic heat production (M) of placental animals (most mammals) can be estimated

by the following formula:

(Equation 10.5)

(Equation 10.5)

where w is the mass of the animal in kilograms. Another useful equation relates the

metabolic heat produced by the body to the rate of oxygen consumption (ASHRAE Handbook,

1981):

(Equation

10.6)

(Equation

10.6)

where

- RQ = the respiratory quotient, or ratio of

produced to

produced to  inhaled;

RQ in man may vary from 0.83 (resting ) to over 1.0 ( heavy exercise)

inhaled;

RQ in man may vary from 0.83 (resting ) to over 1.0 ( heavy exercise)

= oxygen consumption in

liters/minute at standard conditions (O°C 760 mmHg)

= oxygen consumption in

liters/minute at standard conditions (O°C 760 mmHg)- 5.87 = the energy equivalent of 1 L of oxygen at standard conditions in watt-hours/liter

when RQ = 1.

Formulas for the metabolic heat production of other classes of animals can

be found in an article by Gordon (1977).

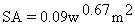

- Another widely accepted form for expressing metabolic heat production is power per unit

surface area. The dashed line in Figure 10.4, with a slope of 0.67, represents how surface

area increases with mass for geometrically similar shapes. This corresponds to the

approximate formula for the body surface area (SA) of these animals:

(Equation 10.7)

(Equation 10.7)

Although surface area does not describe the animal data as well as  , it is as suitable a measure as any

for human metabolic heat production. For accurate calculations of human metabolic heat

production, the DuBois area (Equation 10.2) should be used.

, it is as suitable a measure as any

for human metabolic heat production. For accurate calculations of human metabolic heat

production, the DuBois area (Equation 10.2) should be used.

- Metabolic heat production (M) is often called "metabolic rate" (MR). Table

10.2 lists resting metabolic rates for normal healthy humans of varying age and

somatotype. The specific metabolic rate (SMR; W/kg) is clearly seen to be a function of

body size and shape.

- The basal metabolic rate (BMR) is defined as the heat production of a human in a

thermoneutral environment (33ºC), at rest mentally and physically and at a time exceeding

12 h from the last meal. The standard BMR for man is about 250 ml

, or 84 W, or 0.8 MET (where 1 MET = 58.2 W/m² ). The

BMR also corresponds to about 1.2 W/kg for a 70-kg "standard" man. The BMR is

altered by changes in active body mass, diet, and endocrine levels but probably not by

living in the heat (Goldman, 1983). In resting man most of the heat is generated in the

core of the body--the trunk, viscera, and brain-despite the fact that these regions

represent only about one-third of the total body mass. This heat is conducted to the other

body tissues, and its elimination from the body is controlled by the peripheral vasomotor

system.

, or 84 W, or 0.8 MET (where 1 MET = 58.2 W/m² ). The

BMR also corresponds to about 1.2 W/kg for a 70-kg "standard" man. The BMR is

altered by changes in active body mass, diet, and endocrine levels but probably not by

living in the heat (Goldman, 1983). In resting man most of the heat is generated in the

core of the body--the trunk, viscera, and brain-despite the fact that these regions

represent only about one-third of the total body mass. This heat is conducted to the other

body tissues, and its elimination from the body is controlled by the peripheral vasomotor

system.

- Table 10.3 shows the wide variation of metabolic rates during various activities. All of

these data are given for a healthy normal 20- to 24-yr-old male except as noted. The range

of metabolic rate for humans--considering work performed and assorted physiological

variables such as age, sex, and size--is roughly 40 to 800 W/m² (1 to 21 W/kg for

"standard" man), depending on physical fitness and level of activity. The

influence of age and sex on the metabolic rate of humans is shown in Figures 10.5 and

10.6. Other factors that may influence the metabolic rate are endocrine state, diet, race,

pregnancy, time of day, and emotional state. If deep-body temperature is altered, from

either heat storage in warm environments or febrile disease, a comparable change occurs in

the metabolic rate (Stitt et al., 1974). Similar changes occur when deep-body temperature

rises during exposure to RFR (Adair and Adams, 1982).

Table 10.2.

Resting Metabolic Rates For Normal Healthy Humans Of Specific Age and Somatotype (adapted

from Ruch and Patton, 1973)

Table 10.3.

Variation of Metabolic Rate with Activity For a Normal 20-24-Year-Old Male* (adapted from

Ruch and Patton, 1973)

Figure 10.5.

Variation of human resting metabolic rate (RMR), with age and sex, expressed as power per

unit surface area. Data from Ruch and Patton (1973).

Figure 10.6.

Variation of human resting metabolic rate (RMR), with age and sex, expressed as power per

unit body mass. Data from Figure 10.5 converted by means of average height and weight in

Dreyfuss (1967).

- Resting metabolic rates (MR) for some adult laboratory animals are shown in Table 10.4

in three different forms: total MR for the weight given, specific MR, and standardized MR.

Table 10.4.

Resting Metabolic Rates For Adult Laboratory Animals

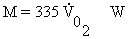

A rough idea of metabolic heat production can be gained from an animal's oxygen

consumption ( ) by using the

formula

) by using the

formula

(Equation

10.8)

(Equation

10.8)

where  = liters of oxygen

consumed per minute. The energy equivalent of oxygen is approximately 4.8 kcal/L

= liters of oxygen

consumed per minute. The energy equivalent of oxygen is approximately 4.8 kcal/L  for a typical animal diet, and the

respiratory quotient (RQ) is approximately 0.85.

for a typical animal diet, and the

respiratory quotient (RQ) is approximately 0.85.

10.6. AVENUES OF HEAT LOSS

- Changes in vasomotor tonus and evaporation of body water through active sweating (or

panting in certain endotherms) are both mechanisms of body heat loss. As detailed in

Section 10.3 (Figures 10.2 and 10.3), vasomotor control normally operates to regulate the

body temperature when an endotherm is in a thermoneutral environment, i.e., within the

TNZ. Sweating (or panting) is activated in warmer environments and during exercise and

defervescence.

10.6.1. Vasomotor Control

- Convective heat transfer via the circulatory system is controlled by the sympathetic

nervous system. Below the LCT, vasoconstriction of the peripheral vasculature in arm, leg,

and trunk skin minimizes heat loss from the skin, leaving a residual conductive heat flow

of 5-9 W/m per ºC difference between body core and skin. For a body in the TNZ, when the

peripheral vessels are vasodilated, each liter of blood at 37ºC that flows to the skin

and returns 1ºC cooler allows the body to lose about 1 kcal, or 1.16 W•h, of heat

(Hardy, 1978). During vigorous exercise in the heat, peripheral blood flow can increase

almost tenfold; this increase is essential to eliminate the increased metabolic heat

produced in the working muscles.

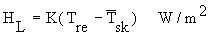

- Tissue conductance (K) represents the combined effect of two channels of heat transfer

in the body--conductive heat transfer through layers of muscle and fat and convective heat

transfer by the blood. Tissue thermal conductance is defined as the rate of heat transfer

per unit area during a steady state when a difference of 1ºC is maintained across a layer

of tissue (W/m² • ºC) Johnson, 1973. Although K cannot be measured directly in the

human organism, it can be estimated for resting humans under the assumption that all the

heat is produced in the core of the body and is transferred to the skin and thence to the

environment. Thus

(Equation 10.9)

(Equation 10.9)

in which  represents the heat

loss (neglecting that lost through respiretion), Tre is rectal or core

temperature, and

represents the heat

loss (neglecting that lost through respiretion), Tre is rectal or core

temperature, and  is the average

skin temperature. In the cold (22-28ºC), conductance is minimal for both men and women,

ranging between 6 and 9 W/m² • ºC. In warm environments conductance increases

rapidly, and women show a faster increase than men (Cunningham, 1970; also see Figure

10.3).

is the average

skin temperature. In the cold (22-28ºC), conductance is minimal for both men and women,

ranging between 6 and 9 W/m² • ºC. In warm environments conductance increases

rapidly, and women show a faster increase than men (Cunningham, 1970; also see Figure

10.3).

- Evaporation of sweat from the skin surface efficiently removes heat even in environments

warmer than the skin. In this case, evaporative heat loss must take care of both metabolic

heat and that absorbed from the environment by radiation and convection. We have no reason

to believe that thermalizing energy from absorbed RFR will be dealt with any differently

than heat produced by normal metabolic processes or absorbed by exposure to warm

environments.

- Normal secretory functioning of the approximately 2.5 million sweat glands on the skin

of a human being is essential to the prevention of dangerous hyperthermia. Secretion is

controlled by the sympathetic nervous system and occurs when the ambient temperature rises

above 30-31ºC or the body temperature rises above 37ºC. Local sweating rate also depends

on the local skin temperature (Nadel et al., 1971). Physically fit individuals and those

acclimated to warm environments sweat more efficiently and at a lower internal body

temperature than normal (Nadel et al., 1974). Dehydration or increased salt intake will

alter plasma volume and decrease sweating efficiency (Greenleaf, 1973).

- The maximum sweat rate for humans and the length of time it can be maintained are

limited. The maximum rate of sweat production by an average man is about 30 g/min. If the

ambient air movement and humidity are low enough for all this sweat to be evaporated, the

maximum cooling will be about 675 W/m²; however, conditions are not usually this

ideal--some sweat may roll off the skin or be absorbed by layers of clothing. A more

practical limit of cooling is 350 W/m², or 6 METS, which represents about 17 g/min for

the average man (ASHRAE Handbook, 1981).

10.7. HEAT-RESPONSE

CALCUIATIONS

10.7.1. Models of the Thermoregulatory System

- The operating characteristics of the thermoregulatory system appear to be similar to

those of an automatic control system involving negative feedback. The body temperature of

endotherms appears to be regulated at a set, or reference, level. Temperature sensors

located in the skin and various other parts of the body detect temperature perturbations

and transmit this information to a central integrator,or controller, that integrates the

sensory information, compares the integrated signal with the set point, and generates an

output command to the effector systems for heat production or loss. The responses thus

mobilized tend to return the body temperature back to the set level.

- These hypothetical constructs aid our understanding of thermoregulatory processes and

let us formulate simulation models that can be used to predict human response to a wide

variety of thermal stressors. Models have been of many types, from verbal descriptions to

highly sophisticated electrical analogs and mathematical models. Hardy (1972) gives a

comprehensive account of the development of modeling in thermal physiology. Many

simulation models have been used to predict human responses to RFR (Farr et al., 1971). Of

particular relevance are the theoretical models of Mumford (1969) and Guy et al. (1973)

that use a heat-stress index to describe man's response to particular environmental and RF

heat loads. A model by Emery et al. (1976b) uses several sweat rates to calculate the

thermal response of the body to absorbed RFR. A model of Stolwijk and Hardy (1966) has

been combined with simulations of RFR energy deposition by Stolwijk (1980) and Way et al.

(1981) to demonstrate that the rise in local temperatures in the human body, especially in

the brain, may be much less than anticipated during the localized deposition of RF energy,

even when the radiation is focused on the hypothalamus. Greatly enhanced evaporative heat

loss, skin blood flow, and conductance serve to protect individual body tissues during RFR

energy deposition. On the other hand, a two-dimensional, combined RF-heat-transfer model

developed by Spiegel et al. (1980) predicts rapid localized temperature increments in the

thigh of a nude male resting at thermoneutrality and exposed to 80 MHz at 50 mW/cm², and

similar temperature increments in the steady state at power densities as low as 10

mW/cm². Adding to this model the altered tissue blood flow for temperatures in excess of

40ºC may modify these predictions.

10.7.2. Data for Heat-Response

Calculations

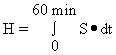

- Much is known about the upper limits of human tolerance to hot, humid environments that

contain no source of RFR (Givoni and Goldman, 1972; Proving et al., 1962). Knowing what

the human tolerance time would be for a given SAR would be useful. This section describes

calculations of the approximate SAR that will produce a critical internal body temperature

in a standard man exposed for 60 min in a specified hot and humid environment.

- The body's two physiological mechanisms that deal with heat stress, vasomotor and

sudomotor, are each a complex function of many variables. The problem can be simplified,

however, if we assume that the body is calling upon its maximum thermoregulatory capacity.

Under most conditions of severe thermal stress, evaporative cooling is limited by the

evaporation rate, not the sweat rate since the maximum sweat rate is over 2 L/h. If the

psychrometric conditions (air temperature, relative humidity, and air velocity), skin

temperature, and clothing characteristics are known, the heat storage in the body can be

calculated by the fundamental heat-balance equation (10.1).

- Agreement is not complete on the physiological criteria that best describe the limits of

human thermal tolerance. Several researchers (Ellis et al., 1964; Craig et al., 1954;

Goldman et al., 1965; Wyndham et al., 1965) have used a rectal temperature (

) of 39.2ºC as a useful criterion for

setting the upper level of heat-stress tolerance in clinical trials. Others have advocated

the use of more subjective criteria such as faintness and loss of mental and physical

ability (Bell and Walters, 1969; Bell et al., 1965; Machle and Hatch, 1947). Since

quantitative calculations based on such subjective criteria are not practical, for the

purposes of the following calculations we have defined a

) of 39.2ºC as a useful criterion for

setting the upper level of heat-stress tolerance in clinical trials. Others have advocated

the use of more subjective criteria such as faintness and loss of mental and physical

ability (Bell and Walters, 1969; Bell et al., 1965; Machle and Hatch, 1947). Since

quantitative calculations based on such subjective criteria are not practical, for the

purposes of the following calculations we have defined a  of 39.2ºC as the danger level for man. With this definition, the

critical rate of heating for a 1-h period is that which will cause a rise in

of 39.2ºC as the danger level for man. With this definition, the

critical rate of heating for a 1-h period is that which will cause a rise in  of 2.2ºC/h, assuming a normal

beginning rectal temperature of 37ºC and neglecting any temporal lag in the

of 2.2ºC/h, assuming a normal

beginning rectal temperature of 37ºC and neglecting any temporal lag in the  response.

response.

- We utilized data for the change in mean skin temperature (

) as a function of time collected in an experiment

recorded by Ellis et al. (1964), in which a healthy 28-yr-old male exposed to a hot, humid

environment was judged by observers to have reached his tolerance limit in 61 min. His

final rectal temperature was 39.4ºC. His skin temperature rose bimodally from 36.9 to

38.4ºC during the first 20 min of exposure, then increased more slowly to 39.3ºC in the

next 41 min because of the onset of sweating.

) as a function of time collected in an experiment

recorded by Ellis et al. (1964), in which a healthy 28-yr-old male exposed to a hot, humid

environment was judged by observers to have reached his tolerance limit in 61 min. His

final rectal temperature was 39.4ºC. His skin temperature rose bimodally from 36.9 to

38.4ºC during the first 20 min of exposure, then increased more slowly to 39.3ºC in the

next 41 min because of the onset of sweating.

- If these data for

and

and  are assumed to be generally true for

a man heat stressed to his tolerance point in 1 h, we should be able to calculate lesser

amounts of heat storage imposed on the body by less severe environmental conditions that

permit greater rates of evaporative cooling. Also, substituting an equivalent amount of

heat energy absorbed during exposure to RFR for metabolic energy seems reasonable. Such an

equivalence was demonstrated by Nielsen and Nielsen (1965) when they measured identical

thermoregulatory responses to exercise and to diathermic heating. This assumption would be

expected to be valid for RFR at frequencies up to the postresonance region (perhaps up to

about 1 GHz for the average man), but might not be valid at higher frequencies where the

RFR causes primarily surface heating. Consequently, the results calculated in the next

section are restricted to radiation conditions where the RF heating does not occur

primarily on the surface. The substituted equivalent RFR heat load, expressed in watts per

kilogram of body mass, is designated the

are assumed to be generally true for

a man heat stressed to his tolerance point in 1 h, we should be able to calculate lesser

amounts of heat storage imposed on the body by less severe environmental conditions that

permit greater rates of evaporative cooling. Also, substituting an equivalent amount of

heat energy absorbed during exposure to RFR for metabolic energy seems reasonable. Such an

equivalence was demonstrated by Nielsen and Nielsen (1965) when they measured identical

thermoregulatory responses to exercise and to diathermic heating. This assumption would be

expected to be valid for RFR at frequencies up to the postresonance region (perhaps up to

about 1 GHz for the average man), but might not be valid at higher frequencies where the

RFR causes primarily surface heating. Consequently, the results calculated in the next

section are restricted to radiation conditions where the RF heating does not occur

primarily on the surface. The substituted equivalent RFR heat load, expressed in watts per

kilogram of body mass, is designated the  --the specific absorption rate that would produce a rectal temperature of

39.2ºC in the irradiated subject in 60 min. The

--the specific absorption rate that would produce a rectal temperature of

39.2ºC in the irradiated subject in 60 min. The  is intended to represent the maximum SAR that a healthy average

man can tolerate, with regard to thermal considerations alone, for 60 min in a given

environment, assuming both that the capacity to thermoregulate is normal and that the

other criteria for metabolic rate, posture, clothing, and behavior specified below are

valid.

is intended to represent the maximum SAR that a healthy average

man can tolerate, with regard to thermal considerations alone, for 60 min in a given

environment, assuming both that the capacity to thermoregulate is normal and that the

other criteria for metabolic rate, posture, clothing, and behavior specified below are

valid.

- For the following calculations the required parameters for man and the environment are

listed in Table 10.5. Standard values obtained from physiology texts (Kerslake, 1972;

Mountcastle, 1974; Newburgh, 1949; Ruch and Patton, 1973) are given for the sample

calculations. The symbols, units, and conversion factors used in this section conform for

the most part to the uniform standards proposed by Gagge et al. (1969).

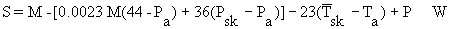

- The calculations are based on a modification of the fundamental heatbalance equation

(10.1) which neglects the work factor (W), groups together the terms for dry-heat losses

(R + C), and incorporates the electromagnetic power absorbed (P):

M + P =

(R + C) + E + S

or

S = M - (R + C) - E + P (Equation 10.10)

in which all symbols are as previously defined. The total heat load is given

by

(Equation

10.11)

(Equation

10.11)

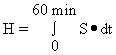

where  is the change in rectal

temperature caused by heat load H. The evaporation rate is given by

is the change in rectal

temperature caused by heat load H. The evaporation rate is given by

(Equation

10.12)

(Equation

10.12)

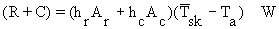

The dry-heat losses due to radiation and convection can be represented by

(Equation

10.13)

(Equation

10.13)

Table 10.5.

Specification Of Parameters Used In Calculating

Combining Equations 10.10, 10.12, and 10.13 and using values from Table 10.5 results in

(Equation

10.14)

(Equation

10.14)

This equation is first solved for the particular psychrometric conditions of interest

with no RF power absorbed (P = 0). Over a 1-h period, the heat load due to the environment

alone is given by

(Equation

10.15)

(Equation

10.15)

The solution is -60 kcal when  and

and  . By Equation 10.11, the heat

load that causes a 2.2ºC rise in

. By Equation 10.11, the heat

load that causes a 2.2ºC rise in  was 128 kcal for this particular man.

was 128 kcal for this particular man.

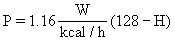

The power, P, that will cause a 2.2ºC rise in  in 1 h is the difference between H and 128 kcal.

in 1 h is the difference between H and 128 kcal.

P = 218 W

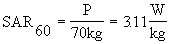

The  is simply

is simply

By using the SAR curves for an average man, we can plot the incident power density that

will produce the  for any given

frequency and polarization, as shown in Figure 10.7. The calculated

for any given

frequency and polarization, as shown in Figure 10.7. The calculated  values plotted on this graph represent the worst

possible case for man, which is, according to the data for the prolate spheroidal model, E

polarization at resonance (70 MHz).

values plotted on this graph represent the worst

possible case for man, which is, according to the data for the prolate spheroidal model, E

polarization at resonance (70 MHz).

- In Figure 10.7 the intercept of each curve with the horizontal axis indicates the

ambient conditions (temperature and relative humidity) that will produce a rectal

temperature of 39.2ºC with no irradiation. For example, with a relative humidity of 80%

and an ambient temperature of 42ºC, the

is zero--which means that under these conditions a rectal temperature of

39.2ºC will occur in 1 h with no irradiation. Similarly, the curve shows that if the

ambient temperature were 41ºC and the relative humidity 80%, the

is zero--which means that under these conditions a rectal temperature of

39.2ºC will occur in 1 h with no irradiation. Similarly, the curve shows that if the

ambient temperature were 41ºC and the relative humidity 80%, the  would be 1.25 W/kg--under these conditions a rectal

temperature of 39.2ºC would be reached in 60 min. The other curves in the figure indicate

that the same SAR (1.25 W/kg) would occur at 49ºC and 50% relative humidity and at 63ºC

and 20% relative humidity. From the ordinate on the right, we read that at this

would be 1.25 W/kg--under these conditions a rectal

temperature of 39.2ºC would be reached in 60 min. The other curves in the figure indicate

that the same SAR (1.25 W/kg) would occur at 49ºC and 50% relative humidity and at 63ºC

and 20% relative humidity. From the ordinate on the right, we read that at this  , the incident power density for E

polarization at resonance would be 5 mW/cm². The incident power densities at other

frequencies and/or polarizations can be determined by using the dosimetric curves to find

what power density produces an SAR of 1.25 W/kg for the given frequency and polarization

in question.

, the incident power density for E

polarization at resonance would be 5 mW/cm². The incident power densities at other

frequencies and/or polarizations can be determined by using the dosimetric curves to find

what power density produces an SAR of 1.25 W/kg for the given frequency and polarization

in question.Figure 10.7.

Calculated  values in an average

man, unclothed and quiet, irradiated by an electromagnetic planewave with E polarization

at resonance (about 70 MHz). Dashed horizontal lines indicate the psychrometric conditions

(in still air) that yield an

values in an average

man, unclothed and quiet, irradiated by an electromagnetic planewave with E polarization

at resonance (about 70 MHz). Dashed horizontal lines indicate the psychrometric conditions

(in still air) that yield an  of

1.25 W/kg and 0.4 W/kg at this frequency.

of

1.25 W/kg and 0.4 W/kg at this frequency.

- If the ambient temperature were 41ºC and the relative humidity only 20%, a very high

SAR would be required to produce a rectal temperature of 39.2ºC in 60 min, a value too

high to be read from Figure 10.7. This shows that, as expected, in warm environments the

relative humidity has a great effect on the body's ability to dissipate an added thermal

burden by evaporation. We strongly emphasize that the

is only an estimate of the upper limit of thermal tolerance for a

healthy nude man. Many other factors must be considered, not the least of which is the

great disparity in thermoregulatory response from individual to individual.

is only an estimate of the upper limit of thermal tolerance for a

healthy nude man. Many other factors must be considered, not the least of which is the

great disparity in thermoregulatory response from individual to individual.

- Figure 10.7 shows the relative independence of the

on the prevailing ambient temperature at any given ambient

humidity level. Thus at such moderate SARs, hyperthermic levels of body temperature can be

expected only if the body is already operating at near-critical environmental conditions.

Under such hostile conditions even small increases in metabolic heat production, such as

very light work, will also initiate an increase in the body temperature. The basis for RF

exposure guidelines currently in force, 0.4 W/kg, is also indicated on the curves in

Figure 10.7 under the assumption of a 60-min average time. (The 6-min averaging time

specified in the current guidelines is far too short to achieve a thermal steady state

such as that represented in Figure 10.7.) The reduction in ambient temperature required,

at any relative humidity, to accommodate an

on the prevailing ambient temperature at any given ambient

humidity level. Thus at such moderate SARs, hyperthermic levels of body temperature can be

expected only if the body is already operating at near-critical environmental conditions.

Under such hostile conditions even small increases in metabolic heat production, such as

very light work, will also initiate an increase in the body temperature. The basis for RF

exposure guidelines currently in force, 0.4 W/kg, is also indicated on the curves in

Figure 10.7 under the assumption of a 60-min average time. (The 6-min averaging time

specified in the current guidelines is far too short to achieve a thermal steady state

such as that represented in Figure 10.7.) The reduction in ambient temperature required,

at any relative humidity, to accommodate an  of 0.4 W/kg is less than can be precisely achieved or measured, given present

technology; therefore, no temperature or humidity factors should be used to adjust

0.4-W/kg RF exposures.

of 0.4 W/kg is less than can be precisely achieved or measured, given present

technology; therefore, no temperature or humidity factors should be used to adjust

0.4-W/kg RF exposures.

- A healthy person exposed to the environments represented in the SAR curves would be

expected to experience considerable thermal discomfort along with the rise in core

temperature, rise in heart rate, and profuse sweating. All of these responses would

increase over time until, at about 60 min, the person would be on the verge of collapse

and exhibiting the unpleasant but reversible symptoms reported in experiments on human

heat tolerance.

- Because of the approximations used in the calculations described here and the great

differences in thermoregulatory response found from person to person, we emphasize that

the calculated data given in this handbook are intended to serve only as guidelines and to

give a qualitative indication of anticipated responses.

Go to Chapter 11.

Return to Table of Contents.

Last modified: June 14, 1997

© October 1986, USAF School of Aerospace Medicine, Aerospace Medical Division (AFSC),

Brooks Air Force Base, TX 78235-5301

![]()

![]() (Equation 10.2)

(Equation 10.2)  =

=![]() =

=![]() (Equation 10.3)

(Equation 10.3) ![]() (Equation 10.4)

(Equation 10.4) ![]() (Equation 10.5)

(Equation 10.5) ![]() (Equation

10.6)

(Equation

10.6) ![]() (Equation 10.7)

(Equation 10.7) ![]() , it is as suitable a measure as any

for human metabolic heat production. For accurate calculations of human metabolic heat

production, the DuBois area (Equation 10.2) should be used.

, it is as suitable a measure as any

for human metabolic heat production. For accurate calculations of human metabolic heat

production, the DuBois area (Equation 10.2) should be used.![]() ) by using the

formula

) by using the

formula![]() (Equation

10.8)

(Equation

10.8) ![]() = liters of oxygen

consumed per minute. The energy equivalent of oxygen is approximately 4.8 kcal/L

= liters of oxygen

consumed per minute. The energy equivalent of oxygen is approximately 4.8 kcal/L ![]() for a typical animal diet, and the

respiratory quotient (RQ) is approximately 0.85.

for a typical animal diet, and the

respiratory quotient (RQ) is approximately 0.85.![]() (Equation 10.9)

(Equation 10.9) ![]() represents the heat

loss (neglecting that lost through respiretion), Tre is rectal or core

temperature, and

represents the heat

loss (neglecting that lost through respiretion), Tre is rectal or core

temperature, and ![]() is the average

skin temperature. In the cold (22-28ºC), conductance is minimal for both men and women,

ranging between 6 and 9 W/m² • ºC. In warm environments conductance increases

rapidly, and women show a faster increase than men (Cunningham, 1970; also see Figure

10.3).

is the average

skin temperature. In the cold (22-28ºC), conductance is minimal for both men and women,

ranging between 6 and 9 W/m² • ºC. In warm environments conductance increases

rapidly, and women show a faster increase than men (Cunningham, 1970; also see Figure

10.3).![]() (Equation

10.11)

(Equation

10.11) ![]() is the change in rectal

temperature caused by heat load H. The evaporation rate is given by

is the change in rectal

temperature caused by heat load H. The evaporation rate is given by![]() (Equation

10.12)

(Equation

10.12) ![]() (Equation

10.13)

(Equation

10.13) ![]() (Equation

10.14)

(Equation

10.14)  (Equation

10.15)

(Equation

10.15) ![]() and

and ![]() . By Equation 10.11, the heat

load that causes a 2.2ºC rise in

. By Equation 10.11, the heat

load that causes a 2.2ºC rise in ![]() was 128 kcal for this particular man.

was 128 kcal for this particular man.![]() in 1 h is the difference between H and 128 kcal.

in 1 h is the difference between H and 128 kcal.![]()

![]() is simply

is simply![]()

![]() for any given

frequency and polarization, as shown in Figure 10.7. The calculated

for any given

frequency and polarization, as shown in Figure 10.7. The calculated ![]() values plotted on this graph represent the worst

possible case for man, which is, according to the data for the prolate spheroidal model, E

polarization at resonance (70 MHz).

values plotted on this graph represent the worst

possible case for man, which is, according to the data for the prolate spheroidal model, E

polarization at resonance (70 MHz).![]()