|

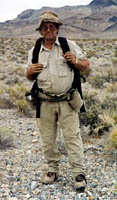

Desert diary: Jerry Freeman chronicles his

|

||||||

Main Story Diary entries

Archives 'New Lost 49ers' complete successful trek across West Modern 49ers struggle over historic Nevada trail

Route map Archive photos

|

Specifically, he

wanted to find and document an inscription made by one of the pioneers thought

to be in Nye Canyon above Papoose Lake on the Nellis Air Force Base

Bombing and Gunnery Range. Last year, he and a group of five followed the 147-year-old trail from western Utah to Death Valley. But the Lost 49ers staggered right through what is now the Air Force range, and Freeman was consistently denied access to any part of Air Force property. As a result, on April 22 of this year, Freeman decided to take matters into his own hands.

Tuesday evening, April 22, 1997

Fidgeting with the straps on my 50-pound pack, I convinced myself I was only waiting for the moon to rise a little higher before setting out, when, in fact, I was afraid. The enormity of what I was about to do eroded my courage. Finally, taking a deep breath, I stepped across the barrier ... and into the "forbidden zone." Earlier that day, I met with Ken McCall, a reporter for the Las Vegas SUN, to apprise him of my surreptitious intent to find an inscription that was believed to have been carved on a remote canyon wall, high above Nevada's mysterious Papoose Lake, nearly 150 years ago. The catch was, the lake and the canyon lie deep within the most guarded real estate on Earth: The U.S. Air Force's Nellis Air Force Base Gunnery Range. "Dreamland," as it is known to military pilots, and "Area 51" to legions of UFO buffs. Five years of pleading with the Air Force to allow my archaeological team to document the route of a lost wagon train, that passed through this wild and desolate land in 1849, had been met with absolute refusal from the military. An appeal from California Congressman "Buck" McKeon on our behalf was dismissed out of hand. They had no interest in meeting with members of my team to discuss the project's merit. Civilian access, regardless of cause, is never granted. A phone call by my former partner, Lee Bergthold, to an Air Force spokesman ended quite abruptly: "NO ... NO ... NO ... HELL, NO!" Naively, I continued to petition them with deference and courtesy, hoping against hope that, at some point in time, the base commander would call me up and say, "Hey, Jerry, we have a little down time on such and such date. Come to the gate and our base archaeologist will run your team in there for a day and see if we can locate that inscription. Your research is commendable, glad we could assist!" Well, so much for fantasy. Now the choices were truly limited: Forget about this critical phase of the '49ers' odyssey and be content with armchair research? Or contemplate the unimaginable -- unlawful entry? Never in my life had I knowingly broken the law. But to actually see Papoose Lake -- a place of monumental importance to those struggling emigrants. To behold, with my own eyes, the rumored 1849 inscription in Nye Canyon. According to pioneer journals, seven inscriptions were carved along their meandering trail, from Utah to Death valley. I personally discovered one and have seen all but this singular etching. The siren call was deafening ... and, ultimately, irresistible. In December, the SUN's McCall had covered our team's month-long expedition to follow the tragic route of this wagon train and I was impressed with his competent style of journalism. I felt it was necessary to establish a link with the media, just in case the wild rumors about trespassers disappearing were true. More importantly, I wanted the public to know there was nothing sinister about my intentions. My only firepower was map and compass ... and for those who would question my patriotism, I will say this: I respect my flag, I worship this country and I would give my life in its defense. A cellular phone was included with my gear. I would use it to keep Doyle, my wife Donna and the Las Vegas SUN informed of my progress. If arrest appeared imminent, I would broadcast my position and circumstances. In no way would I flee or resist detainment. The base is rumored to be protected by ex-Navy Seals and Delta Force personnel. Should I vanish into thin air, a victim of excessive military exuberance, the government would have to extend a reasonable explanation. Admittedly, seeking McCall's confidence was risky. I did not know him well and he was only a phone call away from having me arrested. I often trust my instincts when judging people and fortunately, I called this one right. Leaving the safety of public land, the clarity of the full moon dissipated my feats. Confidence surged with my stride, as it always does when I'm alone in the wilderness. By dawn, I was nearing a nameless pass, which referencing my calculations, would place me above a waypoint of critical importance for the success of this trip: Cane Spring ... and its life-sustaining pool of fresh water.

|