|

Stealth Search for History

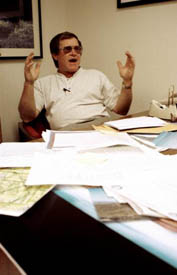

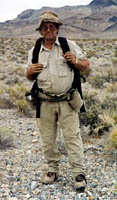

Archaeologist braves barren desert, government security to find lost siteBy Ken McCallLAS VEGAS SUN As the full moon rose on an April night, Jerry Freeman picked up his backpack and headed into a desolate and forbidding landscape.

|

||||||||||

Main Story Diary entries Archives 'New Lost 49ers' complete successful trek across West Modern 49ers struggle over historic Nevada trail

Route map Archive photos |

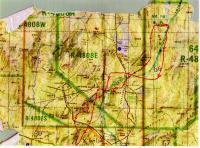

His objective: To find an inscription made in 1849 by a member of a lost and desperate wagon train that eventually gave Death Valley its name. Also, Freeman wanted to see Papoose Dry Lake, the last place where the group of would-be gold-diggers camped together before splintering in search of water. His problem: The dry lake and the canyon that is thought to contain the inscription are deep within one of the nation's most restricted military bases. Freeman's subsequent adventure, described in his own words in a five-part serial that begins today in the SUN, took him through a surreal landscape that included eerie installations, ominous warning signs, a large ship stranded in the desert, and seemingly endless miles of rock and scrub brush. The trek also put him through several heart-stopping close encounters with security, a nerve-wracking moonlight tiptoe across a Test Site "potential crater area," an interview with a surly rattlesnake, and a desperate, dry-mouthed, all-night forced march in search of water. For his troubles, Freeman got a good sunburn, a good look at Papoose Dry Lake and Nye Canyon, and the discovery of an ox shoe likely left behind by the wagon train. But he never found the inscription. By the time Freeman got to Nye Canyon, where the etching is believed to be located, he was almost out of water. He had only a day to search. Freeman knew before he started that the odds were against success and that he stood a good chance of being arrested, but the lure of finding that inscription and seeing the route was too strong. "The siren song is deafening," he said in an interview with the SUN on the afternoon before he set out. "I would be the only individual to see all seven inscriptions. I've seen so much of the trail. I've seen everywhere they went except for that stretch there. "I am smitten by the forbidden fruit." Late last year, Freeman led a group of five on a 32-day, 330-mile trek that followed the route taken by the so-called Lost 49ers. Those impatient pioneers, in November 1849, turned off the well-traveled Spanish Trail near what is now Enterprise, Utah, and headed southwest in hopes of finding a shortcut to the California gold fields. Instead, their unfortunate decision brought them seven weeks of misery, four deaths and the dubious honor of naming Death Valley. Freeman's group had the advantage of modern equipment, knowledge of water sources and a supply truck. But unlike the Lost 49ers, Freeman had to deal with the Air Force. The proposed trek was well-received by the National Park Service and the Bureau of Land Management. In addition, Freeman got the Department of Energy to agree to supervised visits to areas of the Test Site that could have been on the Lost 49ers route. The Air Force, however, ignored or sternly rebuffed all efforts by Freeman and his supporters to gain even limited access to the military base. Freeman, an Antelope Valley, Calif., resident, enlisted the help of his congressman, Buck McKeon, who wrote a letter to the Air Force. To no avail. The reply, Freeman said, was that the Air Force "will not allow nor will they ever allow anyone access to the area." There are seven inscriptions mentioned in the journals of the Lost 49ers, and early in last November's trek, Freeman discovered the previously unknown location of one of them. The team also found an encampment containing artifacts that were likely left by the unfortunate pioneers. Freeman and his group eventually would see all but one of the inscriptions. They had a photograph of the seventh one, taken from a history book. But there is no documentation for the photo, other than it was taken in Nye Canyon near a place called Triple Tanks. After the group trek ended in December, that last inscription -- and the Air Force's obstinacy -- kept eating at Freeman. "When you start a project ... you hope to bring it to a conclusion," Freeman said. "If you leave gaps in it, you don't have a sense of fulfillment." Besides, he said, the Air Force "treated me and my entire crew with disdain." "This is part of our American heritage. I believe I have a right to see it." Freeman came to the SUN because he wanted a neutral party he trusted to know when and why he was going in. "I'm no Rambo," he said before he began his clandestine journey. "I have no death wish here. I'm a middle-of-the-road American guy. I'm not a guy who protests. I pay my taxes. I've never been arrested. "I want the Air Force to know there's nothing sinister about what I'm doing. I'm not interested in the military or technology. I'm interested purely in the history and culture of that site and this artifact. "I'm an archaeologist, that's all I am." Freeman was apprehensive about tales of people venturing into Area 51 never to be seen again. He would take a cellular telephone with him and call in to leave coded messages of his condition and whereabouts. And if he saw he was about to be arrested, he would call in immediately to make sure someone on the outside knew. As he left the office, Freeman still wasn't sure he would attempt the trek. "My wife is totally against this thing," he said. "Any prudent individual would tell me not to do it." But, he admitted, his "sense of adventure" was pulling him. "Nobody's probably been in that canyon and looked around for 50 years. "I may be able to find that inscription." An experienced backwoodsman, Freeman traveled light. He carried no tent or sleeping bag, relying solely on his clothes and an emergency blanket for shelter. Although he had planned to call every day, Freeman left only two phone messages, one at 3 a.m. April 23 and another at 10:27 p.m. April 25. There was nothing after that. On Monday, April 28, Freeman's wife, Donna, said her husband wasn't home yet and his brother, Doyle Freeman, had said Jerry was running a day behind. I finally made contact with Jerry Freeman again the following day. Freeman related highlights of his trek, many of which he called "heart-stopping." "It was high adventure," he said. "I'm lucky. I'm just really lucky." Because he hadn't found the inscription, Freeman wasn't sure he wanted to go public with the story. He wasn't sure it was worth the legal risk. It was agreed to hold any story until he decided he was ready. Two months later, after consultations with friends, family and lawyers, Freeman was ready. He wanted to go public, he said, to bring recognition to the Lost 49ers -- particularly the four pioneer women, "the unsung heroines," who were on that wagon train. Since his group trek last year, Freeman said he has sent story proposals about the Lost 49ers to dozens of magazines and historical journals, but sparked no interest. "I feel we have shortchanged historically that particular group of pioneers," he said. "They suffered through the Great Basin as no one had before. Now it's occupied by government agencies that don't care. They don't care about that inscription or those pioneers." Freeman recognized there would be more interest in his story now that it involves the "Area 51-UFO thing." "If that works," he said, "that's a good thing." Whether Freeman crossed into the Air Force's fabled Area 51 is questionable. Although the Air Force recently acknowledged it has a facility in Groom Dry Lake, it refuses to comment any further on the base, much less define its boundaries. But Area 51 buffs, from studying government maps, have a clear idea where it is located.

In his account and in subsequent interviews, Freeman talked of climbing a ridge above Nye Canyon and looking down on Papoose Dry Lake, which is just south of the mountain. Many UFO buffs -- Freeman is not one of them -- believe a secret hangar containing captured alien spacecraft lies beneath the Papoose lakebed. "During the day I couldn't see anything," Freeman said of his view of the Papoose area. "But at night, it was a different story." Freeman saw several lights. One appeared to be a security vehicle that moved around. Another, however, was stationary and appeared to get larger and smaller -- as would a hangar door as it opened and closed. "But that's purely conjecture on my part," Freeman said. "From that distance, I couldn't tell what it was." Freeman thought he was looking into Area 51, but Campbell, who has written a book about the base, said the archaeologist was still about 10 to 15 miles south of the base, which was hidden from his line of sight by the mountain. Freeman, however, counters that Campbell is working from old maps and doesn't necessarily know what the Air Force considers to be the exact boundaries of its super-secret base. In any case, Freeman said, he wasn't there to see Groom Lake or Area 51. "The 49ers were never at Groom Lake," he said. "They were at Papoose." Freeman still hopes the Air Force will allow some historian -- he realizes he'll likely be blackballed -- to go into Nye Canyon and document the last inscription. "I don't think the general public should be allowed to go in there when they want to," Freeman said. "But for a legitimate educational purpose, I think we should be allowed to document it. I don't see how it would endanger national security to do that. "We do live in a time of relative peace. We're not at war. I think the Air Force needs to lighten up." Freeman also hopes to rekindle interest in pioneer history. "So much of our history has lost its relevance to our young people," he said. "They have no conception what the pioneers went through. "Perhaps my going in there will spark their interest."

|