|

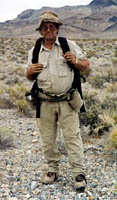

Desert diary: Jerry Freeman chronicles his

|

||

Main Story Diary entries

Archives 'New Lost 49ers' complete successful trek across West Modern 49ers struggle over historic Nevada trail

Route map Archive photos |

Friday morning, April 25, 1997 Just past the "ship," I crossed out of the Department of Energy's jurisdiction and into the Air Force's sacrosanct Nellis Air Force Base Bombing Gunnery Range. I could feel the hairs stand up on the back of my neck. This was "The Dark Side of the Moon," or as one government archaeologist told me in whispered reverence, the "black hole." I had crossed an invisible line into a "nonexistent" area. Here was the proving ground of the supersonic Aurora fighter plane and, most mysteriously, the rumored homeland of the Air Force's fabled collection of alien spacecraft, stored in nine hangars beneath Papoose Lake's alkaline shore. A top-secret realm, I'm told, bristling with underground sensors that detect an intruder's presence immediately, and, if the transgressor is so foolish as to continue, he is certain of a passport to oblivion. Late in the afternoon, I ascended a high, isolated ridge near Nye Canyon and cooked my supper before dark. I wanted no illumination after sunset. Tuna, cheese tortillas and hot chocolate. I'm down to a quart of water. Friday, April 25, 1997, dusk I have discovered my phone link to the outside world has a glitch: It doesn't work. Most of this strange land is without phone signals. Apparently, Pac-Bell is not allowed in here either. Getting through on a cellular phone is possible only from a few places. High ones. Like here. Unfortunately, I needed to be higher still. The ridge I was on narrowed in a steep ascent toward its precipitous top, about 500 feet above my encampment. Climbing it in daylight would be rigorous, ascending it in darkness courted disaster. But I needed to communicate, if only to alleviate the fears of those who waited. A question I've frequently been asked concerns the use of the phone: Couldn't the authorities trace my position when I called? Apparently not. The convoluted nature of the geography and the vagaries of bouncing signals meant that a quick trace was nearly impossible. I'm not suggesting, of course, that a communications command center in the middle of Area 51 could be operated with impunity. We kept our conversations brief and used a simplified code system. The word "mall," for instance, referred to "test site." Any numbers pertained to percentage of mission accomplished. "OK at 50" meant half the journey was completed. Friday night, April 25, 9 p.m. Leaving the bulk of my gear behind, I clipped on my phone, secured my rope and emergency blanket and began climbing by starlight. The moon would not rise until midnight. I reached the summit boulders a little after 10 p.m. Except for a few scrapes and bruises, I was largely intact. I immediately punched in Doyle's number. Eureka! He picked up on the first ring. I told him I was "OK at 50." We moved the exit day back to Monday night, April 28. The "code red" day was moved to Wednesday night, April 30.If I was not out by midnight on the 30th, I probably wasn't coming out. I was either lost, hurt, captured or dead. One fact was certain: Doyle would comply with his instructions. In 30 years of check-pointing my expeditions, he had never failed to be where he was supposed to be, when he was supposed to be there. Loyal Doyle. Called Donna, told her I loved her. Hearing unusual beeping sounds, we cut the call short. Left message on Lee Bergthold's machine: "Yo friend, OK at 50." Phoned McCall at the Las Vegas SUN: "Hi Ken, Jerry at the `mall' looking for jewelry (the 1849 inscription) at 50 percent. Low on water, keep the faith." At last, I reached out over a thousand miles to a climbing buddy in the northwest, Gary Colvin. He suspected where I was, even though all I said was "Hi, newt. I'm deep in the forest, better go." I bedded down on a narrow ledge just below the summit. Tied myself off, just in case. The emergency blanket kept me lukewarm, but the sleeping arrangements hardly made for a comfortable night. Sometime during the climb to the summit, my scabbard broke and my knife is gone.

|