|

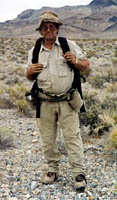

Desert diary: Jerry Freeman chronicles his

|

||

Main Story Diary entries

Archives 'New Lost 49ers' complete successful trek across West Modern 49ers struggle over historic Nevada trail

Route map Archive photos |

Sunday morning, April 27, 1997, 8 a.m. I shook my head in amazement at my good fortune as I stole away from the atomic disposal yard. God, that water tasted great. It would not have mattered if the guard had been "locking and loading" as I approached. I would have walked right up to him, hands over my head. Thirst is such a frightening and insidious need. Today, writing in the comfort of my study, my craving for water seems so remote. Yet this powerful need, above all else, weaves itself like a single thread throughout my narrative. On shorter trips in the desert, or longer ones in the Sierras, water rarely concerned me. It was just a convenience, flowing in a stream nearby or stored in the jeep back at the trailhead, to be used with little regard to its abundance or scarcity. It was always secondary to the exploration of secluded terrain, to viewing of fresh vistas, to the thrill of reaching the summit of an isolated, seldom-climbed peak. Not on this trip. The craving for water or, more precisely, the fear of not finding it threatened at times to consume me, banishing thoughts of anything else. And I was only in the wilderness for a week! The poor '49ers agonized here for nearly a month, struggling across a wasteland as barren and desolate as any on the North American continent. My daughters Jennifer and Holly, along with filmmakers Clay Campbell and Allan Smith, who helped me track the emigrants on all but this forbidden segment of the trail, marveled at their tenacity and perseverance. Being mothers themselves, Holly and Jennifer found the plight of the pioneer women almost too difficult to imagine: "How could they have possibly provided enough nourishment and warmth for their babies?" they asked. One of those brave women, Juliet Brier, reminisced years later about her efforts to save her three small boys:

"Many times I felt that I should faint and, as my strength departed, I would sink on my knees. The boys would ask for water, but there was not a drop. ... Night came, and we lost all track of those ahead. I would get down on my knees and look in the starlight for the ox tracks, and then we would stumble on." Sadly, this remarkable woman lies in an unmarked grave in Lodi, Calif., her exploits largely unknown by the American public. Sunday morning, April 27, 11 a.m. Nearing the Mercury highway, I had an extremely close call with security. Approaching through sparse brush, I had not seen a single vehicle. As it was Sunday, I felt my chances of traversing in daylight were good. Preparing to cross, I could see down the road to the left for miles, so I was not too concerned about traffic surprising me from that direction. But to the right, the road topped a hill hardly a quarter of a mile away. Crouching and half running, I kept my eyes right of center and mentally picked out a small manzanita bush, near the berm on my side of the road, that might provide some cover just in case. Nearing the road, I broke into a full run. When I was withing 10 feet of the pavement, a security pickup topped the hill. Exhaling an "expletive deleted," I dove at a right angle beneath the slim branches of the manzanita. I threw my pack off and shoved it forward, fell flat on my belly and waited. Not more than 10 seconds elapsed before he roared by, none the wiser. As soon as he disappeared, I grabbed my pack and sprinted across the road. Trekking with dogged determination, I made Cane Spring two hours before dusk. Despite my thirst, I circled above the cave and lay concealed in heavy brush till dark, to be certain I was alone. As I lay undercover, Mount Salyer at my back and the spring before me, I was struck by a strange coincidence: Forty-niner scout Lewis Manly, describing his finding of this precious spring in his century-old account, "Death Valley in '49," stated:

"Fearing ambush (from Indians), we approached carefully and cautiously, making a circuit around, so as to get between the hut and the hill."Nearly 150 years later, there I lay, "fearing ambush." After drinking my fill, I recovered the food I had cached on Thursday. Canned chicken for dinner (opening can was accomplished tediously, with a nail and a rock), crackers and chocolate milk, no fire. Inside the shredded cabin, I wrapped my emergency blanket around me and waited for the cover of night and the navigational aid of a full moon.

|