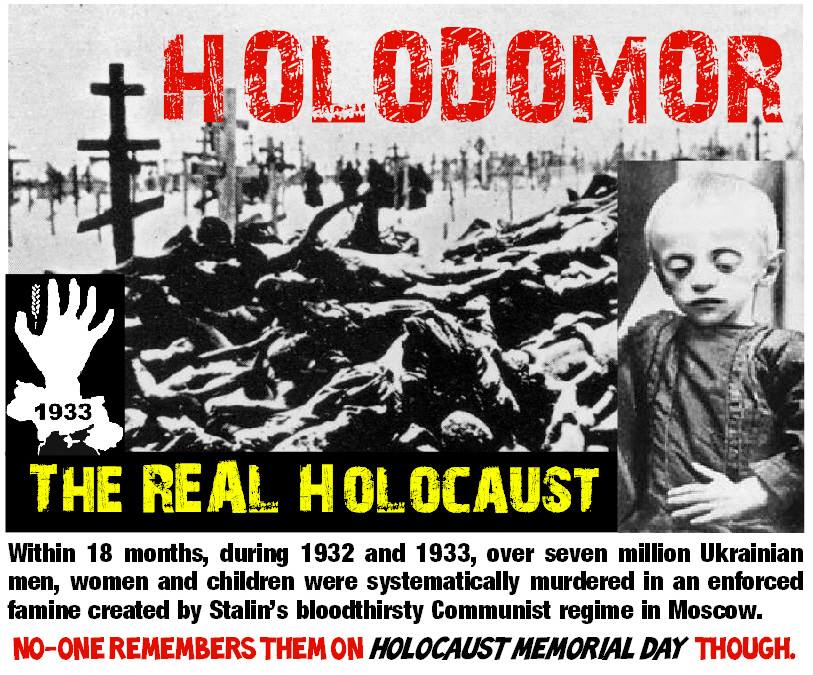

Holodomor: The Secret Holocaust in Ukraine

Written by James Perloff

When Ukraine

resisted Soviet attempts at collectivization in the 1920s and '30s,

the Soviet Union under Stalin

used labor camps, executions, and starvation

(Holodomor) to kill millions of Ukrainians.

In 1933, the recently

elected administration of Franklin D. Roosevelt granted official U.S.

recognition

to the Soviet Union for the first time. Especially repugnant was that this

recognition

was granted even though Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin had just concluded a

campaign

of genocide against Ukraine that left over 10 million dead. This atrocity was

known

to the Roosevelt administration, but not to the American people at large,

thanks

to suppression of the story by the Western press — as we shall show.

Ukraine's Untold Tragedy

The Ukrainian genocide remains largely unknown.

After 76 years, the blood

of the victims still cries for truth, and the guilt

of the perpetrators for exposure.

Many Americans are barely acquainted with Ukraine, even though it is Europe's second

largest country after Russia, and has been a distinct land and people for centuries.

One reason for this unfamiliarity is that Ukraine has rarely known political independence;

it was under Russia's heel throughout much of its existence — under Soviet

domination

prior to 1991, and under Czarist Russia before that. Many American

students heard

little or nothing of Ukraine in their history classes because

the nation had been

relegated to the status of a Russian "province."

Stalin accomplished genocide against Ukraine by two means. One was

massive executions

and deportations to labor camps. But his second tool of murder

was more unique:

an artificial famine created by confiscation of all food. Ukrainians

call this the Holodomor,

translated by one modern Ukrainian dictionary

as "artificial hunger, organized on a vast

scale by the criminal regime

against the country's population," but often simply

translated as "murder

by hunger."

Ukraine was the last place one would have expected famine, for it had been known

for centuries as the "breadbasket of Europe." French diplomat Blaise de Vigenère wrote

in 1573: "Ukraine is overflowing with honey and wax.... The soil of this country is so

good and fertile that when you leave a plow in the field, it becomes overgrown

with grass

after two or three days. It will be difficult to find." The 18th-century

British traveler

Joseph Marshall wrote: "The Ukraine is the richest province

of the Russian empire....

The soil is a black loam.... I think I have never seen

such deep plowing as these

peasants give their ground."

In the aftermath of the 1917 Russian Revolution,

Ukraine became part of a bloody

battlefield of fighting between the Bolsheviks

(the group that eventually became the

Communist Party of the Soviet Union), Czarist

Whites, and Ukrainian nationalists.

Ultimately, of course, the Bolsheviks prevailed,

but Lenin shrewdly recognized that

concessions would be necessary to gain Ukraine's

cooperation as a member of the

unstable young USSR. To exploit Ukrainians' long-standing

resentment of Czarist domination,

he permitted them to retain much of their national

culture. Ukrainians experienced a

relatively high degree of freedom extending

into the mid-1920s. The Ukrainian Autocephalous

Orthodox Church and non-communist

Ukrainian Academy of Sciences were allowed to

operate independently. However,

as the Soviet Union consolidated its power, and

Joseph Stalin ascended to the

party's top, these freedoms became expendable,

and Ukrainian nationalism, at

first exploited, now became viewed as a liability.

Coerced

Collectivization

Despite a communist push for collectivization, Ukraine's farms had mostly remained

private —

the foundation of their success. But in 1929, the Central Committee

of the Soviet Union's

Communist Party decided to embark on a program of total

collectivization. Private

farms were to be completely replaced by collectives

— in Ukraine known as kolkhozes.

This was, of course, consistent

with Marxist ideology: the Communist Manifesto had called

for abolition

of private property.

Intense pressure was placed upon Ukrainian peasants to join the kolkhozes. Twenty-five

thousand fanatical young communists from the USSR's cities were sent to Ukraine to

compel the transition. These became known as the Twenty-Five Thousanders; each

was assigned a particular locality, and was accompanied by a weapons-bearing communist

entourage, including members of the GPU (secret police, forerunner

of the KGB). A communist commission was established in each village.

Holodomor survivor Miron Dolot, in his book Execution by Hunger, describes what

happened soon after a commission was started in his village by

its

Twenty-Five Thousander, Comrade Zeitlin:

We did not have to

wait too long for Comrade Zeitlin's strategy to reveal itself.

The first incident occurred very early on a cold January morning in 1930 while people

in our village were still asleep. Fifteen villagers were arrested, and

someone said that the Checkists [GPU] had arrived in the village

at midnight....

The most prominent villagers were among those arrested.... This was frightening.

Our official leadership had been taken away in one night. The farmers,

mostly illiterate and ignorant, were thereby left much more defenseless.

The leaders of Dolot's village were never seen

again.

Throughout

Ukraine, the Twenty-Five Thousanders held mandatory village meetings

in which they demanded that all peasants relinquish private farming and "volunteer"

to join a collective. Most peasants fiercely resisted. In principle, of course, there is nothing

wrong with farmers pooling their resources and efforts in a cooperative venture.

But this was not what the communists meant by collectivization. On the kolkhozes,

the government owned everything — the land, animals, equipment, and produce.

The worker kept no fruits of his labor, and was at the state's mercy to receive a pittance of pay.

Soviet collectives

never succeeded. As the eminent Sovietologist Robert Conquest noted

of them,

"Wherever they had existed they had, with all the advantages given them by

the

regime, done worse than the individual farm." On the kolkhozes, livestock, poorly

cared for, easily died, and equipment fell into disrepair. This was because the workers

did not own them, nor did they have any stake in the collective. This illustrated the

conflict between Marxist ideology and the reality of human nature. Making matters

worse, the collectives were organized by the Twenty-Five Thousanders, who, being

urban youths, had no agricultural experience; their ignorance of

farming

basics often became the butt of jokes among local Ukrainians.

To force the villagers into collectives, the communists threatened

them with being

declared enemies of the state, to be dealt with by the GPU. Jails

— unfamiliar to

Ukrainian peasants — began appearing in every village.

To instill additional fear,

Soviet army units were brought in, lodging themselves

in homes without permission.

Torturous punishments were devised, such as "path

treading," in which a resisting

peasant would be forced to walk through

the snow to the next village, there to be

interrogated by its officials, and

if he still refused to join a collective, walk to the next

village. This would

carry on until the peasant either died of exhaustion or bent to the

state's will.

A very effective method was to simply seize a family's food supply.

Threatened

with seeing their children starve, many peasants gave in.

By the summer of 1932,

80 percent of Ukraine's farmland had been forcibly collectivized.

Scapegoat for Communist Failure

But since the kolkhozes failed to produce

as predicted by Marxist theory, and with

many peasants still refusing to join,

Stalin sought a scapegoat. It was announced

that the failure of collectivization

was due to sabotage by "kulaks." These were the

more prosperous peasants.

Merely owning a cow, hiring another peasant, or having

a tin roof (instead of

the more common thatched roof) were all considered evidence

that one was a kulak.

Of course, in any

economy, some people thrive more than others. This is usually

owing to industriousness

and efficiency. According to Marxist doctrine, however,

all wealthier peasants

(kulaks) were "bloodsuckers" and "parasites" who had grown

rich by exploiting poorer peasants and who were now subverting collectivization.

Stalin

announced that the solution to better grain production was to "struggle against

the capitalist elements of the peasantry, against the kulaks," and he proclaimed the

goal of "liquidation of the kulaks as a class." In reality, however, Ukraine had

never had a distinct social class of kulaks — this concept was a Marxist invention.

Those accused of being kulaks were either shot,

deported to remote slave labor camps

in Russia, or put in local labor details.

Few survived. One could be accused of being a

kulak on the flimsiest evidence.

Some peasants accused others merely out of envy

or dislike. As one Soviet writer

later noted: "It was easy to do a man in; you wrote a denunciation;

you

did not even have to sign it. All you had to say was that he had paid people to work

for him as hired hands, or that he had owned three cows." Some very poor peasants

were accused of being kulaks simply because they were religiously devout. And ironically,

many of the "rich" kulaks earned less income than the communist officials prosecuting them!

"Dekulakization" slaughtered millions.

Ironically, this process killed off the most

productive farmers, guaranteeing a smaller

harvest and a more impoverished Soviet

Union. The remaining farmers did not dare

take steps to improve their lands or

prosper, for fear they would be reclassified as kulaks.

But Stalin accomplished

his true goal: destroying leadership

that might oppose the complete subjugation

of Ukraine.

This campaign extended beyond kulaks to broadly attacking all vestiges

of Ukrainian nationalism. As Dolot notes, the Soviet Communist Party

sent [Pavel] Postyshev, a sadistically

cruel Russian chauvinist, as its viceroy to

Ukraine.

His appointment played a crucial role in the lives of all Ukrainians. It was

Postyshev who brought along and implemented a new Soviet Russian policy in

Ukraine. It was an openly proclaimed policy of deliberate and unrestricted destruction

of everything Ukrainian. From now on, we were continually reminded

that there were

"bourgeois-nationalists" among

us whom we must destroy.... This new campaign

against

the Ukrainian national movement had resulted in the annihilation of the

Ukrainian central government as well as all Ukrainian cultural, educational, and social institutions.

The Ukrainian Language Institute, Ukrainian Institute of Philosophy, Ukrainian State

Publishing House, and countless other institutions were purged, their leaders murdered

or imprisoned. So fanatical was the war on nationalism that even the colorful embroidered

national costumes Ukrainians wore were seized. Eyewitness Yefrosyniya Poplavets recalls:

"To save our embroidered shirts we put them on under our old ragged jackets. It didn't work!

They undressed us and took the shirts to eradicate any national spirit in the household."

But perhaps the

most intense thrust was against the church, for it represented not only

a form

of Ukrainian solidarity, but the Gospel whose principles inherently oppose those

of

Marxism. The Communist Party declared: "The church is the kulak's agitprop."

Priests were executed or sent to labor camps; church land was confiscated; monasteries

were closed. The churches — some of them centuries-old national monuments —

were either demolished, or turned into cinemas, libraries, barracks and other secular

uses for the state. Church icons were smashed; books and archives were burned;

church bells were even sold as scrap. By the end of 1930, 80 percent of all Ukraine's

village churches had been shut down. These measures were applied not only against

Ukraine's Orthodox churches, but against other denominations and

religions,

for as Marx had said, "Religion is the opiate of the masses."

"Murder by Hunger"

Yet the worst still awaited Ukraine. By 1932,

virtually all kulaks had been liquidated,

but many of the remaining poor peasants

still resisted communism and collectivization.

Stalin now began war upon Ukraine's

poorest — ironically those who,

in Marxist doctrine, should have been esteemed

as "the proletariat."

In 1932, Stalin demanded that Ukraine increase its grain output by 44 percent.

Such a goal would have been unachievable even if the communists had not already

ruined the nation's productivity by eliminating the best farmers and forcing others onto

the feeble collectives. That year, not a single village was able to meet the

impossible quota, which far exceeded Ukraine's best output in the pre-collective years.

Stalin then issued

one of the cruelest orders of his dark career: if quotas were not

met, all grain

was to be confiscated. As one Soviet author much later wrote: "All the

grain

without exception was requisitioned for the fulfillment of the Plan, including

that set aside for sowing, fodder, and even that previously issued to the kolkhozniki

as payment for their work." The authorization included seizure of all food from all

households. Any home that did not turn over all its grain was accused of "hoarding"

state property. One villager recalled the process by which communist "brigades"

invaded homes:

Every brigade had a so-called "specialist" for searching out grain.

He was equipped with a long iron crow-bar with which he probed for

hidden grain.

The brigade went from house

to house. At first they entered homes and asked,

"How

much grain have you got for the government?" "I haven't any.

If you don't believe me search for yourselves," was the usual laconic answer.

And so the "search" began. They searched in the house, in the attic,

shed, pantry

and the cellar. Then they went outside

and searched the barn, pig pen, granary

and the straw

pile. They measured the oven and calculated if it was large enough

to hold hidden grain behind the brickwork. They broke beams in the attic, pounded

on the floor of the house, tramped the whole yard and garden.

If they found a suspicious-looking spot, in went the crow-bar.

Miron Dolot

recalls:

They measured the thickness of the walls, and inspected them for bulges where

grain could have been concealed. Sometimes they completely tore

down suspicious

walls.... Nothing in the houses remained

intact or untouched. They upturned

everything: even

the cribs of babies, and the babies themselves were thoroughly

frisked, not to mention the other family members. They looked for "hidden grain"

in and under men's and women's clothing. Even the smallest amount that was

found was confiscated. If so much as a small can or jar of seeds

was found that

had been set aside for spring planting,

it was taken

away, and the owner was accused of hiding

food from the state.

Of course, to avoid starvation, nearly every family did attempt to conceal food.

But experience soon made the brigades proficient at detecting even the most clever hiding places.

The result was

mass starvation that took millions of lives during the terrible winter

of 1932-33.

Food was nearly impossible to find anywhere. Many begged

neighbors for potato

skins or other scraps — only to find their neighbors equally destitute.

There was still some food on the collectives,

which the communists did not deplete like

households. However, in August 1932

the Communist Party of the USSR had passed a

law mandating the death penalty

for theft of "social property." Watchtowers were built

on the collectives,

manned by trigger-happy young communists. Thousands of peasants

were shot for

attempting to take a handful of grain or a

few beets from the kolkhozes,

to feed their starving families.

Unable to get food, many ate whatever could pass for it — weeds, leaves, tree bark,

and insects. The luckiest were able to survive secretly on small woodland animals.

American journalist Thomas Walker wrote:

About twenty miles south of Kiev (Kyiv),

I came upon a village that was practically

extinct

by starvation. There had been fifteen houses in this village and a population

of forty-odd persons. Every dog and cat had been eaten. The horses and oxen had

all been appropriated by the Bolsheviks to stock the collective farms. In one hut

they were cooking a mess that defied analysis. There were bones,

pig-weed, skin,

and what looked like a boot top in this

pot. The way the remaining half dozen

inhabitants eagerly

watched this slimy mess showed the state of their hunger.

A few people even resorted to cannibalism, eating

those

who had died and, in some cases, murdering those still living.

Many peasants attempted

to reach Ukraine's cities like Kiev, where factory workers

were still allowed

a little pay and food. However, in December 1932 the communists

introduced the

"internal passport." This made it impossible for a villager to

get

a city job without the Party's permission, which was almost universally denied.

Other peasants hoped to get to Poland, Romania,

or even Russia, where there was

no famine. But emigration was strictly forbidden.

Ukrainian train stations were swamped

with the starving, who hoped to sneak aboard

a train, or beg in hopes that a passenger

on a passing train might throw them

a bread crust. They were repelled by GPU guards,

who found themselves faced with

the problem of removing countless corpses of

the starving who littered these

stations.

Horror

of Genocide

British journalist Malcolm Muggeridge, who secretly investigated Ukraine without

Soviet permission, was able to escape communist censorship by sending

details

home to the Manchester Guardian in a diplomatic bag. He reported:

On a recent visit to the Northern Caucasus

and the Ukraine, I saw something

of the battle that

is going on between the government and the peasants.... On

the one side, millions of starving peasants, their bodies often swollen from

lack of food; on the other, soldier members of the GPU carrying out the instructions

of the dictatorship of the proletariat. They had gone over the country like a swarm

of locusts and taken away everything edible; they had

shot or exiled thousands of

peasants, sometimes whole

villages; they had reduced some of the most fertile

land

in the world to a melancholy desert.

At the famine's height, 25,000 people per day were dying. As the

winter wore on,

Ukraine became a panorama of horror. The roadsides were filled

with the corpses

of those who died seeking food. The bodies, many of which snow

concealed

until the spring thaw, were unceremoniously dumped into mass graves

by the communists.

Many others died of starvation in their own homes. Some chose to end the process by

suicide, commonly by hanging — if they had the strength to do it. "They just sat,"

writes Dolot of his fellow villagers, "or lay down silently, too feeble even to talk.

The bodies of some were reduced to skeletons, with their skin hanging grayish-yellow

and loose over their bones. Their faces looked like rubber masks with large,

bulging,

immobile eyes. Their necks seemed to have shrunk onto their shoulders.

The look in their eyes was glassy, heralding their approaching death."

The communists,

on the other hand, ate excellent rations, and party bosses even

enjoyed luxurious

ones. In Robert Conquest's Harvest of Sorrow,

we read the following account

of the party officials' dining hall at Pohrebyshcha:

Day and night it was guarded by militia keeping the

starving peasants away from

the restaurant.... In the

dining room, at very low prices, white bread, meat, poultry,

canned fruit and delicacies, wines and sweets were served to

the district bosses.... Around these oases famine and death were raging.

But perhaps the

worst paradox: although much of the confiscated grain was exported

to the West,

large portions were simply dumped into the sea by the Soviets, or allowed

to

rot. For example, a huge supply of grain lay decaying under GPU guard at Reshetylivka

Station in Poltava Province. Passing it in a train, an American correspondent saw

"huge pyramids of grain, piled high, and smoking from internal combustion." In the

Lubotino region, thousands of tons of confiscated potatoes were allowed to rot,

surrounded by barbed wire.

All this underscores the true purpose of the food confiscation: genocide. Sergio Gradenigo,

the Italian consul in Moscow, wrote in a dispatch to Rome on May 31, 1933:

The famine has been

deliberately planned by the Moscow government and implemented

by means of brutal requisition. The definite aim of this crime is to liquidate the Ukrainian

problem over a few months, sacrificing from 10 to 15 million people. Do not consider

this

figure to be exaggerated: I'm sure it could even

have been reached and exceeded by now.

While there is disagreement over how many lives the genocide claimed,

Gradenigo's

figures have turned out to be rather accurate. In Harvest of

Sorrow, historian Robert Conquest,

considered by many the leading authority

on the famine, put the toll at 14.5 million. About

half of these deaths represent

the liquidation of the kulaks, via execution and slow

death in gulags, while

the famine itself claimed the lives of approximately seven million,

including

three million children.

Helping Stalin Hide the Holocaust

How did a holocaust of these dimensions remain unknown in the West?

First, the

Soviets suppressed all information regarding the famine. Russia's

state-controlled

press was prohibited from discussing it, and for ordinary citizens,

just mentioning the famine carried a penalty of three to five years' imprisonment.

Although some Western

observers did report the magnitude of the Ukrainians' plight,

such comments were

extremely rare. During the famine, the Soviets prohibited foreign

journalists

from visiting Ukraine. But just as significant was the cooperation of influential

Western writers sympathetic to communism. The Fabian Socialist George Bernard Shaw,

after receiving a tour carefully orchestrated by the Soviets, proclaimed in

1932:

"I did not see a single under-nourished person in Russia, young or old."

But by far the worst offender was Walter Duranty,

New York Times' Moscow bureau

chief from 1922 to 1936. Duranty enjoyed

personal access to Stalin, called him

"the greatest living statesman,"

and even praised the dictator's notorious show trials.

To call Duranty a Soviet

sympathizer greatly understates his role. Journalist Joseph Alsop

termed Duranty

a "KGB agent," and Malcolm Muggeridge called him

"the greatest

liar of any journalist I have met in 50 years of journalism."

Duranty's published denials of Ukraine's Holodomor were perhaps

the vilest acts of

his career. In November 1932, he brazenly told his New

York Times readers,

"There is no famine or actual starvation nor is

there likely to be." He denounced as

"liars" the few brave writers

who reported the famine, which he called "malignant propaganda."

When

accumulating reports made the massive deaths hard to dispute, Duranty switched

tactics from outright denial to downplay. He wrote in the Times in March 1933:

"There is no actual starvation or deaths from starvation but there is widespread mortality

from deaths due to malnutrition."

Incredibly, Duranty was awarded a Pulitzer Prize in 1932 for

"dispassionate, interpretive reporting of the news from Russia."

Some will ask: did the Ukrainians resist the

genocide? Yes! Throughout Stalin's war,

hundreds of riots and revolts, on various

scales, erupted throughout Ukraine. There are

even a number of stories where

groups of heroic women overran the communist-guarded

kolkhozes and seized

grain for their starving children. And it

was not unusual for a village's local

party tyrant to suddenly be found dead.

However, such resistance was brutally suppressed. The Soviets had passed gun

registration decrees in 1926, 1928, and 1929, and few Ukrainians owned effective

weapons. Resistance largely constituted pitchforks against machine guns. The GPU

and Soviet army dealt with revolts; aircraft were brought in to suppress the

more serious ones. And the famine of 1932-33 left peasants too weak to resist.

Triumph

at Last, Tragedy Not Forgotten

The Holodomor stands as a permanent warning of what happens when unlimited state

power destroys God-given rights. A cursory review of America's Bill of Rights demonstrates

that virtually every right mentioned was trampled on by Stalin in Ukraine. Yet although

the dictator used every means to eradicate the people's will, the national

spirit lived on unbreakably, until Ukraine gained its independence in 1991.

Here in the United States, Ukrainian-American

organizations such as the

Ukrainian Congress Committee of America (UCCA), Ukrainian Genocide Famine Foundation,

and others work diligently to maintain awareness of the Holodomor.

Last year, they

helped commemorate the genocide's 75th anniversary. And largely

thanks to their efforts,

in 2008 the U.S. House of Representatives passed a resolution

deploring the genocidal famine.

One of UCCA's ongoing campaigns — which

The New American heartily

endorses — is for the long-deserved revocation

of Walter Duranty's Pulitzer Prize.

James Perloff is the author of

The Shadows of Power: The Council on Foreign Relations and the American Decline

_______________________________